Mount Vesuvius Didn't Kill Everyone in Pompeii. Where Did the Survivors Go?

When Mount Vesuvius erupted in A.D. 79, the volcano's molten rock, scorching debris and poisonous gases killed nearly 2,000 people in the nearby ancient Italian cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum.

But not everyone died. So, where did the refugees, who couldn't return to their ash-filled homes, go?

Given that this was the ancient world, they didn't travel far. Most stayed along the southern Italian coast, resettling in the communities of Cumae, Naples, Ostia and Puteoli, according to a new study that will be published this spring in the journal Analecta Romana. [Preserved Pompeii: A City in Ash]

Pinpointing the refugees' destinations was a huge undertaking, as historical records are spotty and scattered, said study researcher Steven Tuck, a professor and chair of classics at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. To determine where people went, he devised several criteria to look for while combing through the historical record, which included documents, inscriptions, artifacts and ancient infrastructure.

For example, Tuck made a database of family names that were distinct to Pompeii and Herculaneum and then checked whether these names showed up elsewhere after A.D. 79. He also looked for signs of unique Pompeii and Herculaneum culture, such as the religious worship of Vulcanus, the god of fire, or Venus Pompeiana, the patron deity of Pompeii, that surfaced in the nearby cities after the volcanic eruption.

Public infrastructure projects that sprung up about this time, likely to accommodate the sudden influx of refugees, also provided clues about resettlement, Tuck said. That's because between 15,000 and 20,000 people lived in Pompeii and Herculaneum, and the majority of them survived Vesuvius' catastrophic eruption.

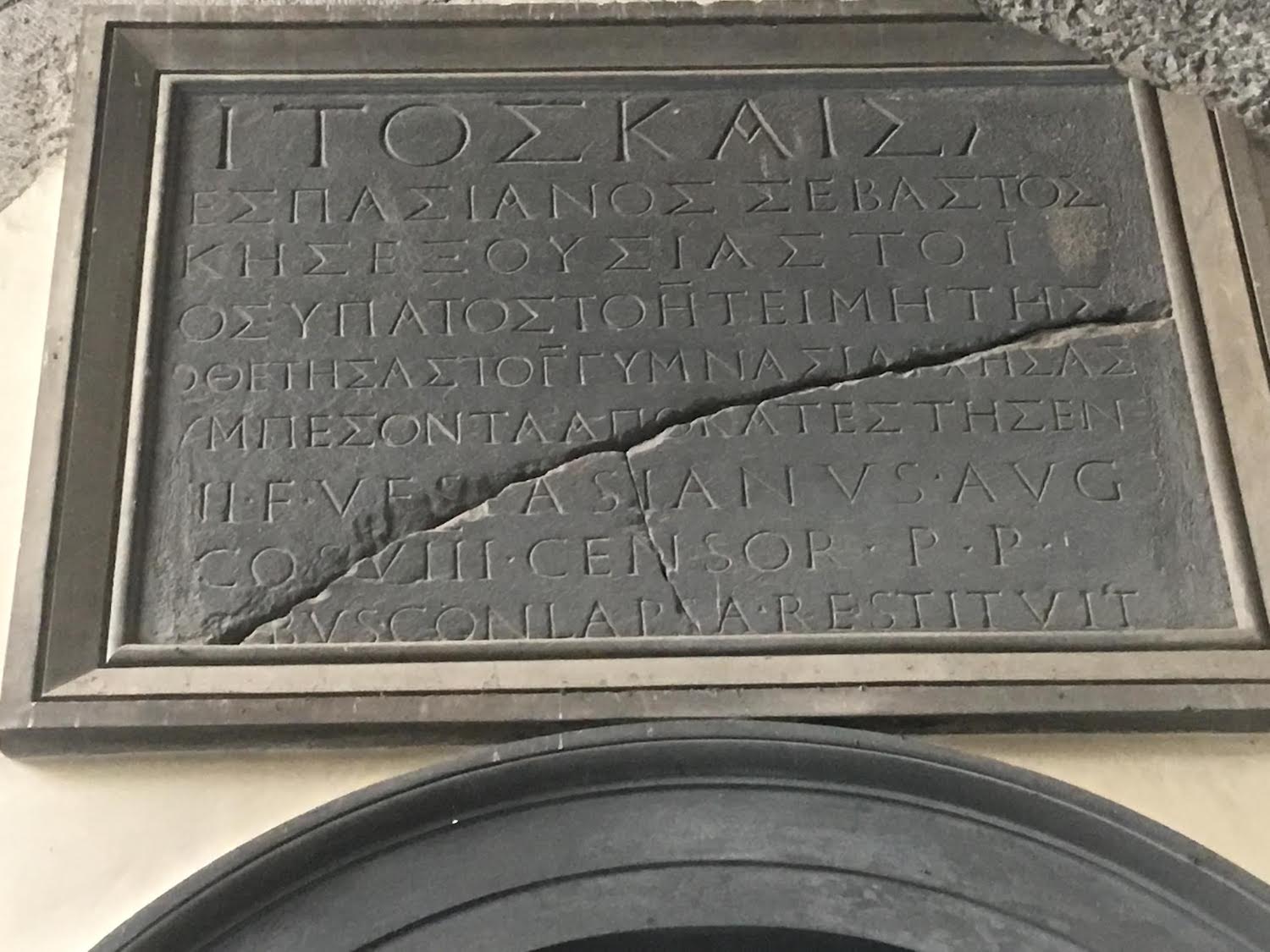

One of the survivors, a man named Cornelius Fuscus later died in what the Romans called Asia (what is now Romania) on a military campaign. "They put up an inscription to him there," Tuck told Live Science. "They said he was from the colony of Pompeii, then he lived in Naples and then he joined the army."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In another case, the Sulpicius family from Pompeii resettled in Cumae, according to historical documents that detail their flight and other records, Tuck said.

"Outside the walls of Pompeii, [archaeologists] discovered a strongbox (similar to a safe) full of their financial records," he said. "It was on the side of the road, covered by ash. So clearly, someone had taken this big strongbox when they fled, but then about a mile outside the city, dumped it."

The documents in this strongbox detailed several decades' worth of financial loans, debts and real estate holdings. It appears that the Sulpicius family members chose to resettle in Cumae because they had a business social network there, Tuck said.

During his research, Tuck also found resettlement evidence for quite a few women and freed slaves. Many refugees married each other, even after they relocated to new cities. One such woman, Vettia Sabina, was buried in a family tomb in Naples with the inscription "Have" adorning it. The word "have" is Oscan, a dialect that was spoken in Pompeii both before and after the Romans took over the city in 80 B.C. "It means 'welcome,' you see it on the floor in front of houses as a welcome mat [in Pompeii]," Tuck said. [Image Gallery: Pompeii's Toilets]

However, looking at unique family names can get you only so far. "My study actually drastically undercounts the number of Romans who got out," Tuck said, as many foreigners, migrants and slaves didn't have recorded family names, making them difficult to track.

Regarding public infrastructure, Tuck found that the Roman Emperor Titus gave money to cities that had become refugee hotspots. This money actually came from Pompeii and Herculaneum — basically, the government helped itself to the money of anyone who died in the eruption who didn't have heirs. Then, this money was given to cities with refugees, although Titus took credit for any public infrastructure that was built, Tuck noted.

"The people whose money went into that fund don't ever get credit," he said.

Despite this, the new infrastructure likely helped the refugees settle into their new homes.

"The cities Pompeii and Herculaneum were gone," Tuck said. "But the government is obviously building new neighborhoods and aqueducts and public buildings in communities where people have settled."

- Pompeii Photos: Archaeologists Find Skeletal Remains of Victims of Vesuvius Eruption

- In Photos: A Journey Through Early Christian Rome

- Photos: Gladiators of the Roman Empire

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.