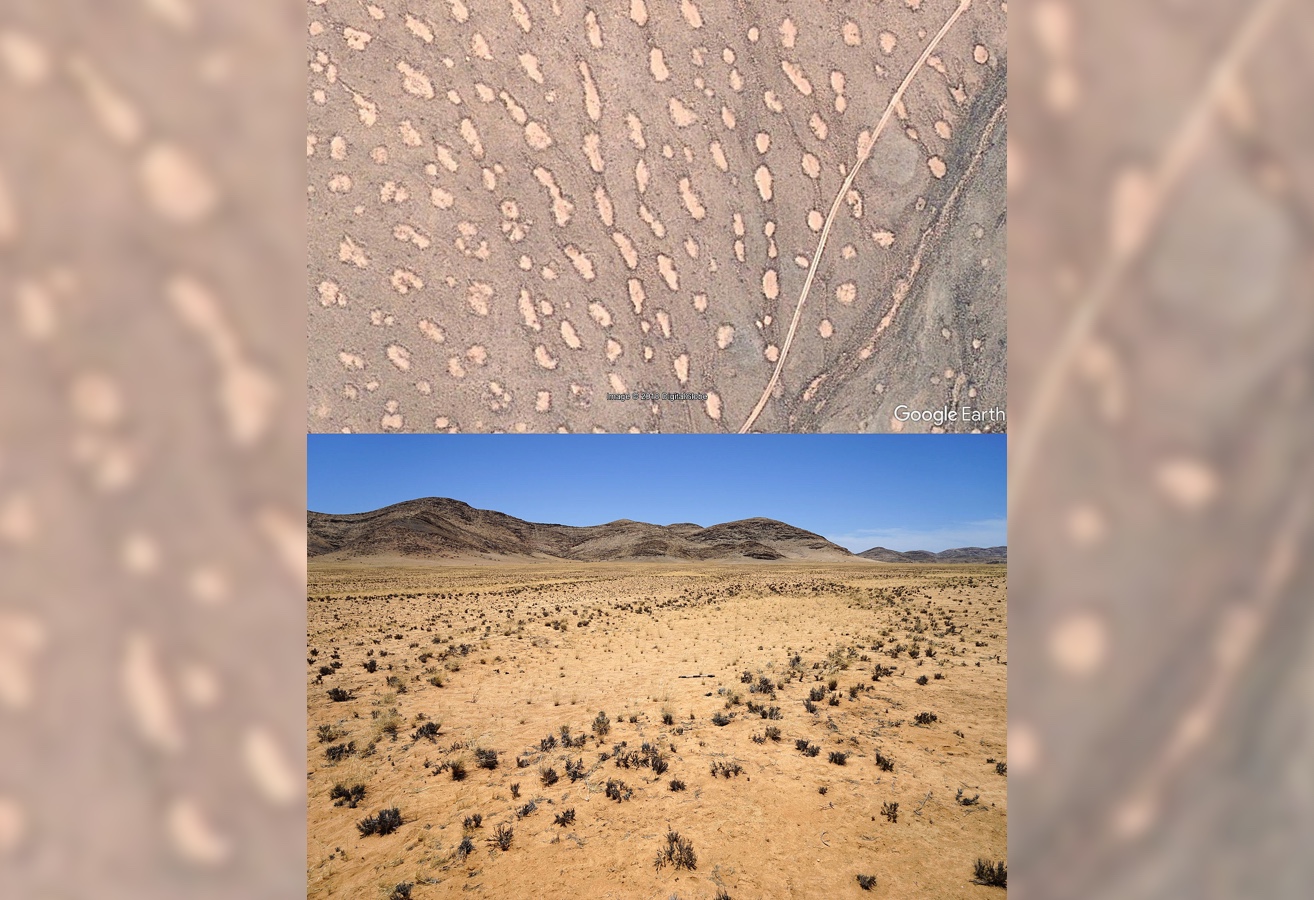

Barren Desert 'Fairy Circles' Caused by … Rain?

Unusual bare circles in the grasslands of Australia and the Namib Desert called "fairy circles" aren't the work of termites, new research suggests.

Fairy circles are a long-standing mystery. Some scientists have argued that they mark termite nests or are the result of plants competing for scarce resources. Some say that a combination of termite and plant activity resulted in the odd splotches. But now, a new study suggests that the circles aren't the result of anything living. Rather, they're a result of weathering caused by heavy rainfall and evaporation.

Termites sometimes nest within fairy circles, study researcher Stephan Getzin of the University of Göttingen in Germany said in a statement. But there is no evidence that the termites are actually creating the bare patches. [In Photos: Mystical Fairy Circles Grace African Desert]

Mapping the circles

Getzin and his colleagues focused on the fairy circles in the Australian desert near the town of Newman. They used drones to visualize the circles from above and excavated samples from 48 separate fairy circles spread over 7.4 miles (12 kilometers). They compared the aerial photos of the fairy circles with bird's-eye views of known harvester termite nests.

"The vegetation gaps caused by harvester termites are only about half the size of the fairy circles and much less ordered," Getzin said.

When the team went digging in the circles, they found just a few "termitaria," or termite colonies. Those they did find were small, not the large, cemented dirt that prevents plants from growing over large areas and might cause the barren circles. What the fairy circles did contain, Getzin said, was a lot of clay and compacted soil. Most likely, he and his team concluded, the circles form in cycles of heavy rain and then evaporation under extreme desert heat. In unvegetated soil, they wrote in the open-access journal the Ecological Society of America, heavy rainfall washes fine clay into empty spaces within the soil, essentially sealing it off with a hard "crust" impervious to new plant growth.

"[N]o destructive mechanisms, such as those from termites, are necessary for the formation of distinct fairy circle patterns," Getzin said. "Hydrological plant-soil interactions along are sufficient."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Namibian mystery

In a second study published in the Journal of Arid Environments, Getzin and his colleague Hezi Yizhaq of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in Israel used satellite imagery to study the patterns of fairy circles in Namibia. Most research on Namibian fairy circles has focused on the weirdly ordered, almost hexagonal pattern seen in fairly flat grassland conditions, they wrote. But in places where the topography is more varied or conditions are unusual, the fairy circles form different patterns. [Image Gallery: Amazing 'Fairy Circles' of the Namib Desert]

In drainage areas, for example, the researchers noticed oval fairy circles more than 98 feet (30 m) across. In extremely arid spots, they found very irregularly spaced circles. They also noted some "mega circles" more than 65 feet (20 m) in diameter. That research was just a pilot study, the researchers wrote, but it highlights questions about the plant and soil dynamics outside of the eye-catching, very regular fairy-circle patterns.

Getzin and his colleagues argue that to have fairy circles, a region must have very homogenous soil, just one or two plant species with particular growth patterns and a just-right balance of rain and evaporation. Those requirements could explain why fairy circles are seen in only two deserts on Earth.

- 25 Strangest Sights on Google Earth

- Visible Only From Above, Mystifying 'Nazca Lines' Discovered

- Photos: Strange Structures in China's Gobi Desert

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.