Photos: The Ram-Headed Sphinx of Gebel el-Silsila

Lost sphinx

The broken head of a ram-headed sphinx sticks out of the rubble in the Egyptian desert. Workers and archaeologists at the Gebel el-Silsila quarry site excavated this 3,370-year-old sculpture and found its broken crown, the shape of a coiled cobra, sitting at its base. The sphinx may have been commissioned to match a series of sphinxes found at a temple site called Karnak near Luxor.

Fragmented history

Near the sphinx, archaeologists found hundreds of hieroglyphic fragments that once belonged to a shrine to the pharaoh Amenhotep III. Son of Thutmose IV, Amenhotep ruled between about 1390 B.C. and 1350 B.C. It was during Amenhotep III's reign that the Gebel el-Silsila quarry opened. Excavations have revealed that a thriving community of workers and their families lived onsite.

Hieroglyphics

A fragmented bit of stone bearing hieroglyphics found at Gebel el-Silsila. The new sphinx is the third sphinx found at the site, which was the source of much of the striking sandstone used in Ancient Egyptian temples and monuments. The newly unearthed sphinx was found with a smaller sphinx sculpture nestled along its belly; that small sculpture may have been a practice statue carved by an apprentice.

Digging out

Workers dig a trench to excavate a large stone "criosphinx" (a sphinx with a ram's head) from quarry rubble at the Nile-side side of Gebel el-Silsila. The debris around the sphinx consisted of fine shavings of sandstone and miniscule iron filings left by ancient chisels, said project assistant director John Ward. More sculptures and tools might be beneath the feet of rubble around the sphinx.

Before excavation

The ram's head — missing its uppermost part — sticks out of the ground at Gebel el-Silsila. Archaeologists knew that more of the statue lurked under the quarry rubble. Workers dug a trench some 12 feet (3.5 m) deep to reach the base of the statue, which measures 16.4 feet (5 m) long and nearly 5 feet (1.5 m) wide. The broken parts of the statue's head and its cobra-shaped crown were found at the statue's base, indicating that they broke off long ago.

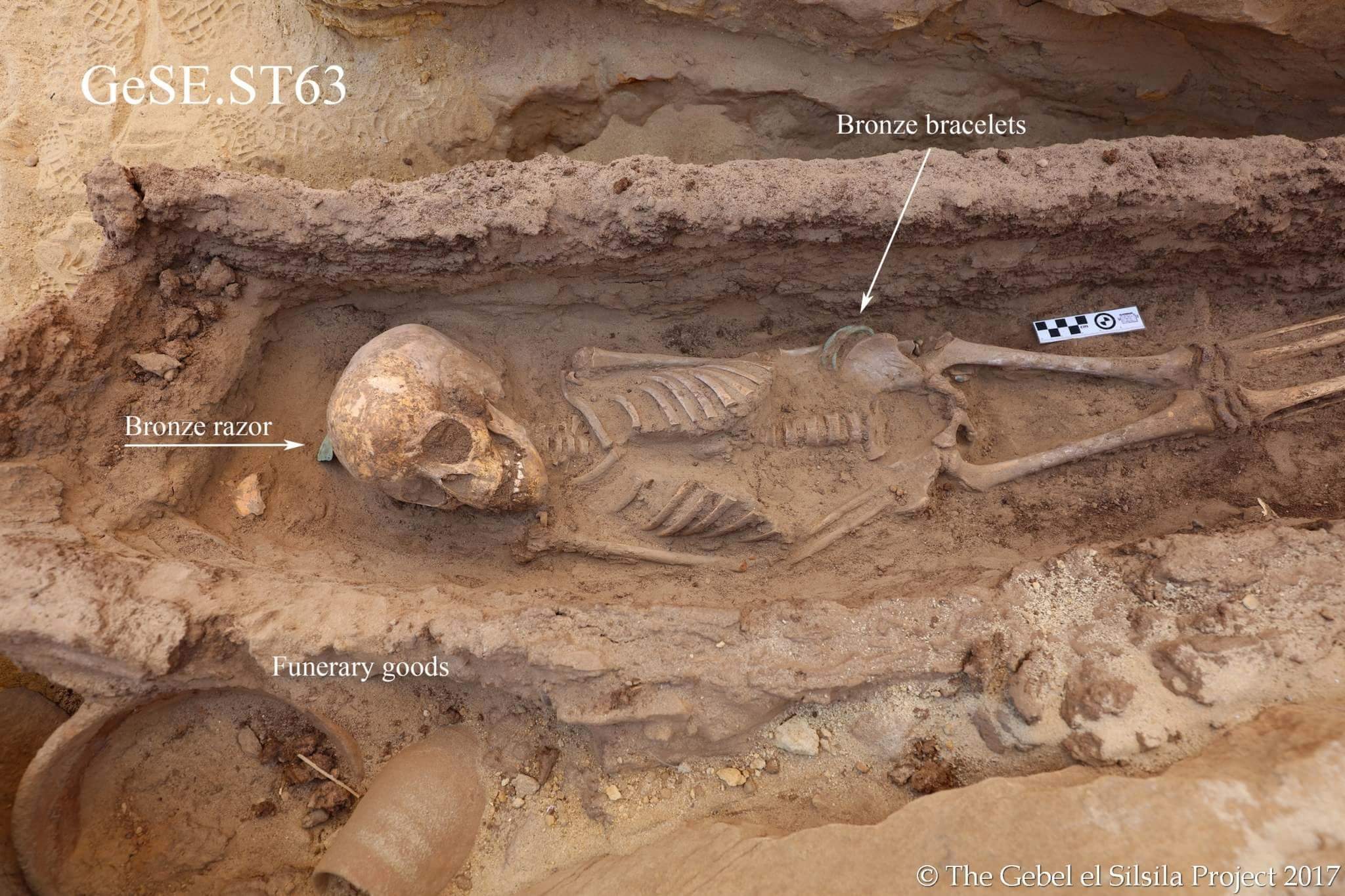

Flooded Tomb

Water floods an unlooted tomb at Gebel el-Silsila. The remains of at least 50 ancient Egyptians were interred here, and archaeologists found several sarcophagi. Two were sized for infants or young children. Artifacts found amidst the muck included beads, pottery fragments and shabti figures, which were meant to represent servants in the afterlife.

Gebel el-Silsila

An aerial view of the Gebel el-Silsila site along the banks of the Nile River. The ancient quarry sits just north of the city of Aswan. Excavations at the site have unearthed quarries, workshops, shrines and tomb niches. Most tombs in the area were long ago looted, but the excavation team recently discovered one tomb containing the remains of at least 50 people.

Child's grave

The skeleton of a child found in a separate tomb at Gebel el-Silsila. The child was between 6 and 9 years old at death and was buried with scarabs, bracelets, amulets and pottery. The discovery of the remains of women and children at the quarry site indicates that it wasn't just a place for workers, but a thriving community where families made their homes.

Beneath the desert

Before excavation, the broken ram's head was easy to miss among the sandstone rubble of Gebel el-Silsila. Archaeologists have discovered three carved sphinxes at the site, and hope that the layers around the latest sphinx might contain other artifacts from the era of Amenhotep III, such as tools. The sand around the sphinx is rich in iron filings left by ancient chisels.

Cobra crown

Excavation project assistant director John Ward examines a fragment of a uraeus, the cobra crown used in ancient Egypt to symbolize royalty or deity. This coiled cobra would have crowned the ram-headed sphinx; its fragments were found at the base of the statue, along with some pieces of the top of the ram's head.

Removing Rubble

Workers remove tons of rocky rubble from around the ram-headed sphinx. The piece was buried with only its head sticking out from about 12 feet (3.5 meters) of quarry spoil, said project assistant director John Ward. "These guys are absolutely tremendous," Ward said of the workers who do most of the labor to uncover the finds at Gebel el-Silsila. "They are diligent, they're enthusiastic, they know exactly what they're doing."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.