Secret Group of Killer Whales Discovered in Southern Ocean

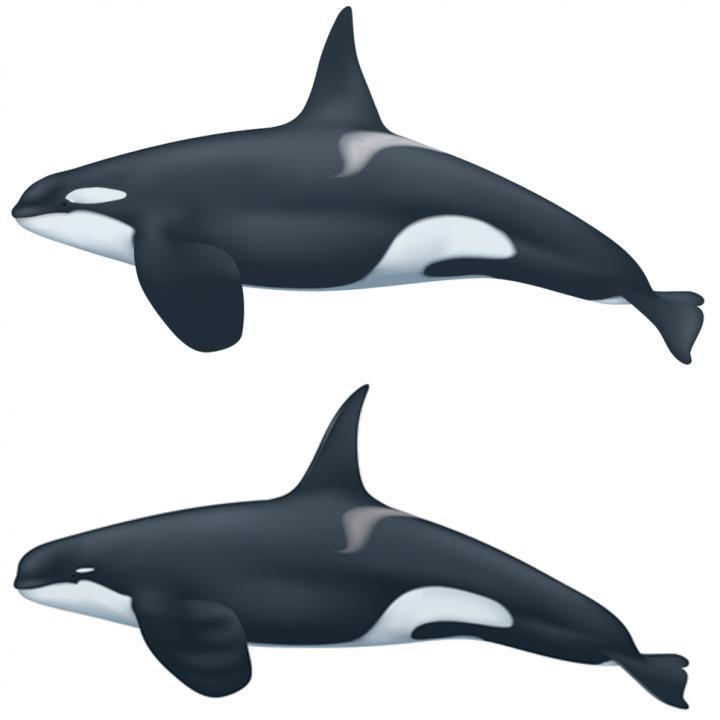

Killer whales are beautiful and majestic, but there's very little variation in what they look like — their shape, size and coloring are pretty standard from whale to whale. So, when people started spotting killer whales with a noticeably different physique — thinner, with much smaller white eye patches and narrower, sharp dorsal fins — scientists paid attention.

In January, an international team of researchers tracked down these potential killer whale imposters and collected samples for genetic testing that will reveal whether or not the animals are a newfound, distinct species of killer whale.

"We are very excited about the genetic analysis to come," Bob Pitman, a researcher from NOAA Fisheries' Southwest Fisheries Science Center in La Jolla, California, said in a statement. "Type D killer whales could be the largest undescribed animal left on the planet and a clear indication of how little we know about life in our oceans." [In Images: Meet the Top 10 Newfound Species]

Not a fish story, after all

Until now, the existence of this potentially newfound species was based only on stories from fishers and a handful of photographs.

The first record of these mysterious whales dates back to 1955 when 17 of the animals stranded on the coast of New Zealand. While their markings resembled known killer whales, these animals were smaller, with a blunt snout and bulbous head. The stranded whales also had narrower, pointy dorsal fins and much smaller white patches above their eyes compared with typical killer whales. Experts speculated that the unusual whales were simply a product of a genetic aberration that existed in only those individuals.

Then, in 2005, a French scientist showed Pitman photos of some odd-looking killer whales that were stealing fish from fishers in the Crozet Islands in the southern Indian Ocean. The whales looked just like the ones that had stranded in New Zealand, more than 5,500 miles (9,000 kilometers) away. This suggested that the unique whales were more widespread than previously thought.

For the next few years, Pitman and his colleagues collected thousands of images from tourists and vessels operating in the Southern Ocean. By 2010, Pitman and his team had collected six images of the wanna-be killer whales, which they dubbed the "Type D" killer whale.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The photos of the Type D whales were snapped at latitudes that often experience the worst boating conditions on the planet — areas known as the Roaring 40s and Furious 50s because of the treacherous winds in the region. If the Type D whales liked to hang out in those spots, then it was no wonder humans hadn't laid eyes on the whales until recently.

The final piece of the puzzle

After years of gathering information about a potentially undescribed species of killer whale, Pitman ventured out to sea to find the mysterious creature. He recruited an international team of marine mammal experts to come with him. In January 2019, the team left the shores of Argentina and found a pod of about 30 Type D whales.

The team spent about 3 hours with the group of whales, all the while recording the sights and sounds of the encounter above and below the water. The researchers also collected three biopsies, or tiny bits of skin, from the whales, which will undergo genetic testing to reveal how closely related the Type D whales are to typical killer whales.

According to Pitman and his team, the discovery of the Type D killer whale serves as a reminder of how much we have left to learn about life in our oceans.

- Whale Album: Giants of the Deep

- Image Gallery: Russia's Beautiful Killer Whales

- Images: Sharks & Whales from Above

Originally published on Live Science.

Kimberly has a bachelor's degree in marine biology from Texas A&M University, a master's degree in biology from Southeastern Louisiana University and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She is a former reference editor for Live Science and Space.com. Her work has appeared in Inside Science, News from Science, the San Jose Mercury and others. Her favorite stories include those about animals and obscurities. A Texas native, Kim now lives in a California redwood forest.