Early Animal Life Exploded on Earth Even Earlier Than Once Thought

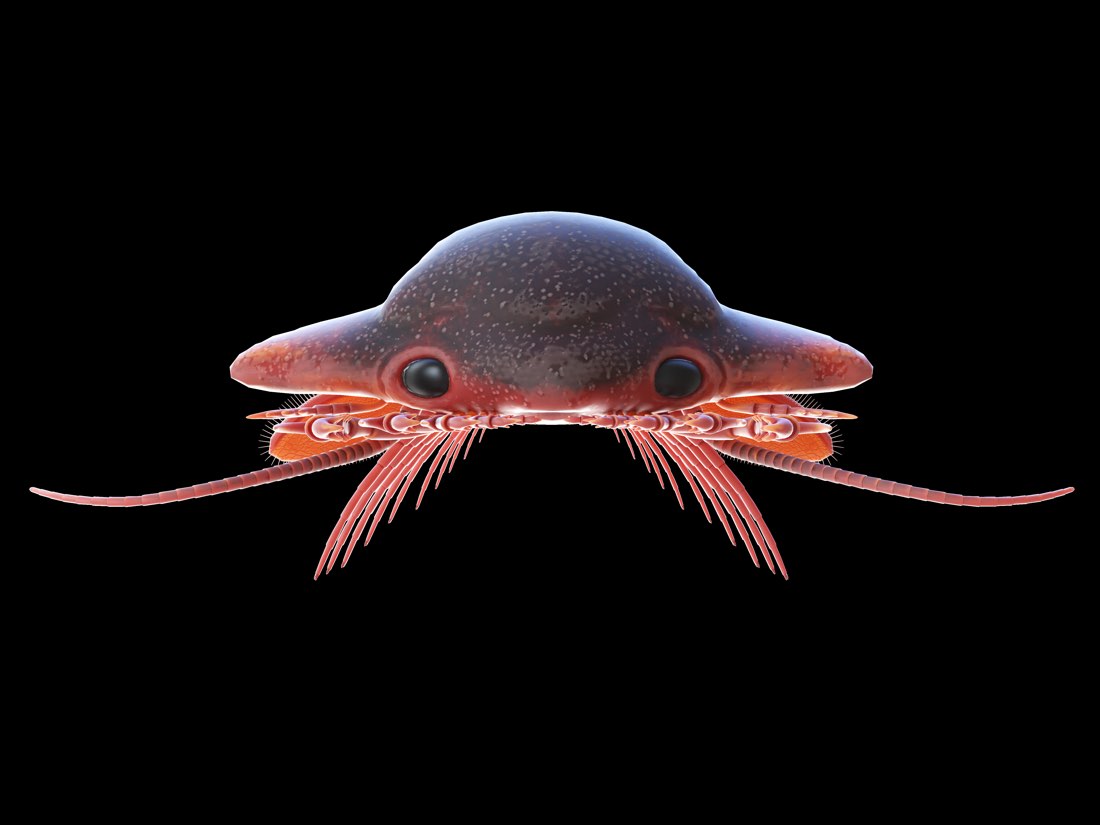

Beginning about 541 million years ago, life on Earth exploded. Over a 53-million-year period, gigantic sea creatures, armored worms and bizarre-looking filter feeders filled the primordial seas. Nearly all the animal body plans that exist today first appeared in primitive form during that time.

Or so scientists thought.

In fact, a new analysis suggests that the Cambrian explosion may not have been a true explosion at all, but rather a series of waves — and those waves began millions of years earlier than previously believed. [These Bizarre Sea Monsters Once Ruled the Ocean]

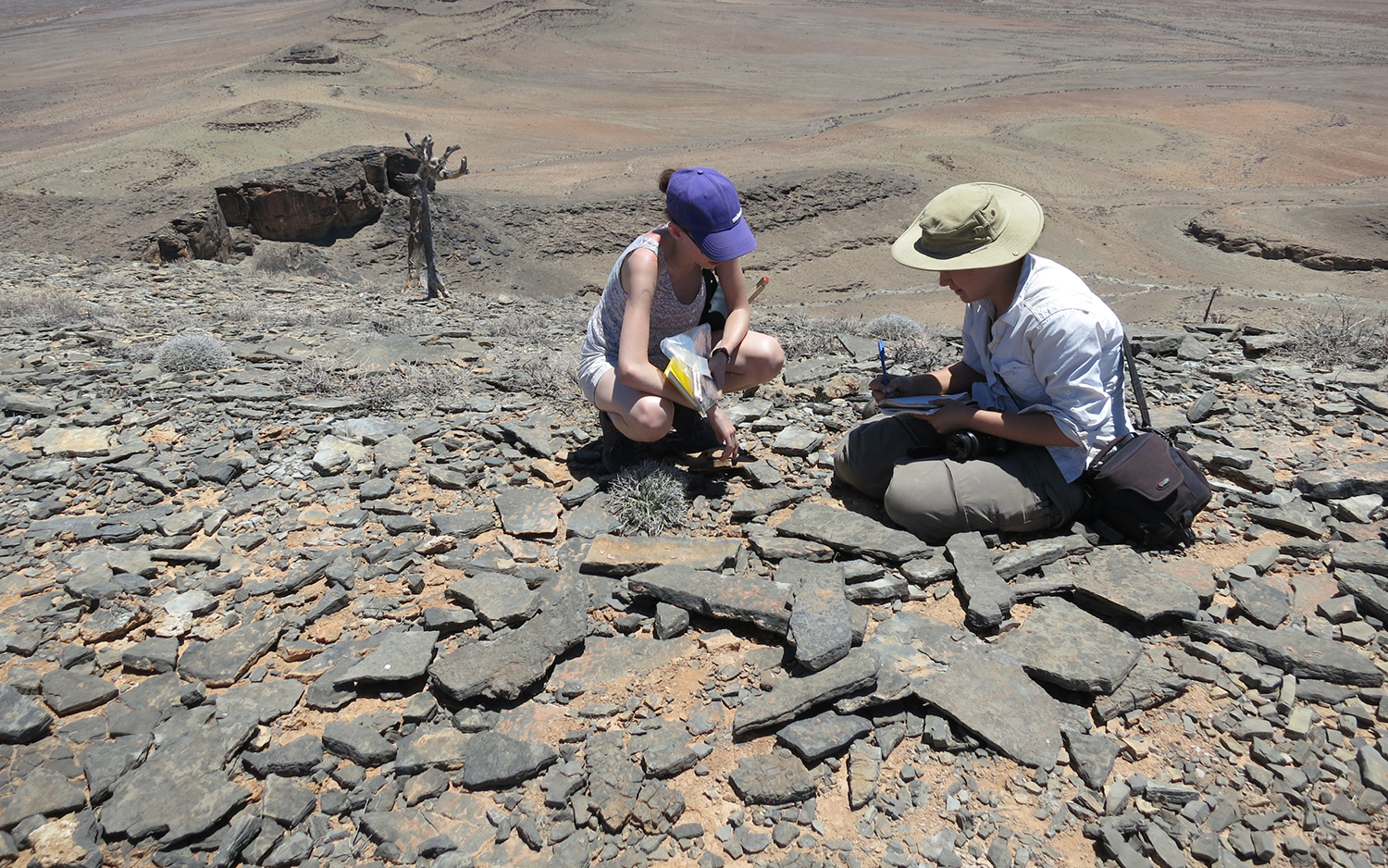

Since the days of Charles Darwin, scientists have found Cambrian-era rocks that were chock-full of fossils. Those fossils seemingly appear in the geologic record "in an abrupt way and with great diversity," said lead study author Rachel Wood, a professor of carbonate geoscience at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland.

"There's no doubt that in the Cambrian there was an explosion of bilaterian forms [bodies with two symmetrical sides] — that's all the animals except the sponges, corals, jellyfish and so on," Wood told Live Science.

But recent fossil discoveries dating to the Ediacaran period (635 million to 542 million years ago) suggest that many new soft-bodied species first arose long before creatures with skeletons showed up during the Cambrian, Wood told Live Science.

For the study, the researchers conducted a sweeping evaluation of existing research in fields such as geochemistry, stratigraphy and paleontology, Wood said. They also analyzed fossil finds from both the Ediacaran and the Cambrian, creating the first integrated picture of what happened before, during and after the Cambrian explosion.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

They discovered that some physical features found in Cambrian creatures were also present in organisms from older rocks. These collections of creatures form a transitional bridge "between what was thought to be typically Ediacaran and what is typically Cambrian," Wood said.

The scientists also noted that changes swept through early animal life in waves, beginning as early as 571 million years ago and producing multiple surges in animal diversity during the Cambrian.

"It begs the question: Is it sensible to isolate the Cambrian explosion as one event, or should it simply be seen as one event amongst many?" Wood said.

Their conclusions, while "not shocking news," were absent from prior studies because most researchers tended to focus on "the abruptness, explosiveness, and uniqueness of the Cambrian explosion," Shuhai Xiao, a professor of geobiology in the Department of Geosciences at Virginia Tech, told Live Science in an email.

Xiao, who was not involved in the study, said that paleontologists will now need to untangle the evolutionary relationships between Ediacaran and Cambrian fossils to determine how big the extinctions were before the Cambrian explosion.

The new study will help scientists to study early animal diversity as a continuous process, "rather than just thinking it all happened in a very short period of time in the Cambrian," Wood said.

"We'll start to be able to really understand the pace and the dynamics of evolution, and the origin of animal complexity," she added.

The findings were published online March 11 in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution.

- Cambrian Period & Cambrian Explosion: Facts & Information

- These Bizarre Sea Monsters Once Ruled the Ocean

- Photos: 508-Million-Year-Old Bristly Worm Looked Like a Kitchen Brush

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.