Why Do Cambrian Creatures Look So Weird?

A spiky worm with legs like noodles. A giant predator that looks like a cross between a walrus and a housefly. Many animals that evolved during the Cambrian period, 541 million to 485 million years ago, seem bizarre compared with modern life-forms. Even paleontologists sometimes wonder: Why do Cambrian creatures look so strange?

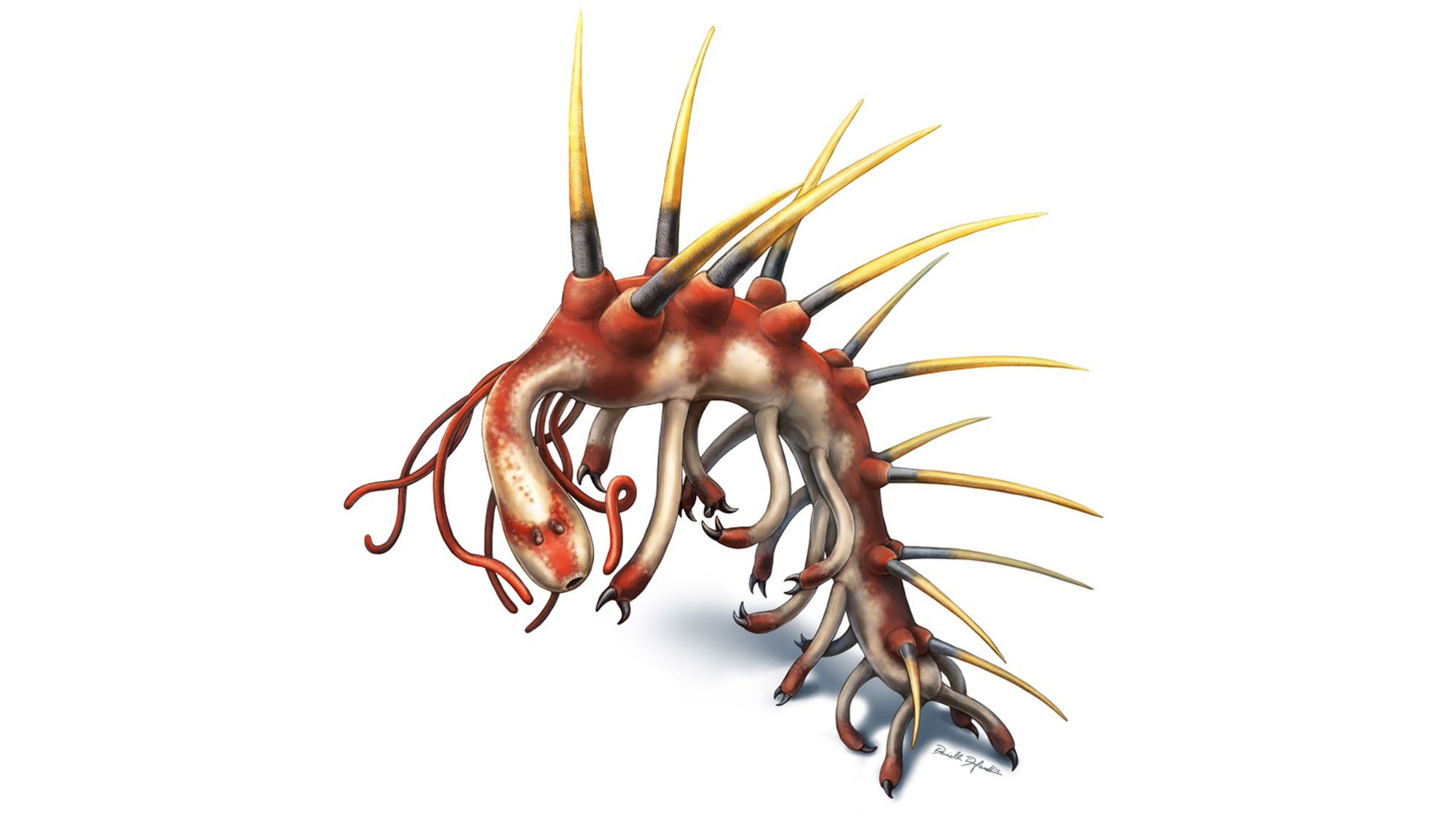

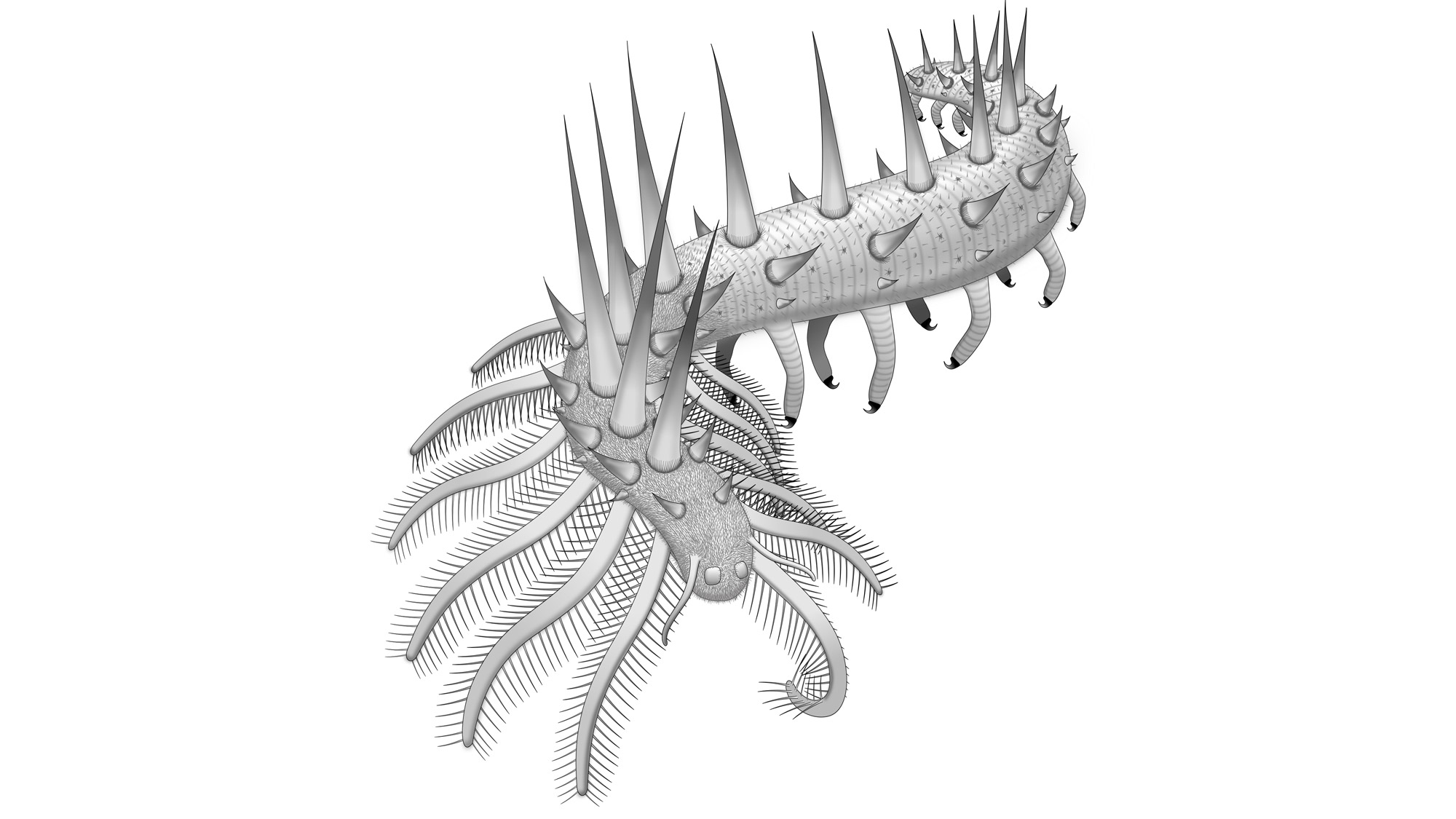

Animals from this ancient time are certainly distinctive. One of the better-known is Hallucigenia, a worm named for its resemblance to the product of a fever dream. Fossils of the spine-covered creature were first discovered in the 1900s in the Burgess Shale, a famed fossil deposit in the Canadian Rockies. Scientists found Hallucigenia's body shape so confusing that it took years to confirm which end of it was the head.

Another standout is Opabinia, a five-eyed Cambrian invertebrate with a claw dangling from the end of a long, flexible face-nozzle. A group of paleontologists burst out laughing when their colleague, Harry Whittington, first showed them his reconstruction of the fossil at a conference in the 1970s. Whittington took the reaction as "a tribute to the strangeness of this animal" when he recounted it later in his detailed study of Opabinia. He concluded that the animal probably used its awkward facial appendage to dig for food. [Why Don't Fish Have Necks?]

All of these odd-looking animals evolved at a special time in Earth's history, said Javier Ortega-Hernández, an invertebrate paleontologist and assistant professor of organismic and evolutionary biology at Harvard University. For billions of years before the Cambrian period, simple underwater microorganisms were the only living things on Earth. By the beginning of the Cambrian, tiny animals had appeared to eat these microbes. But they stayed on the flat surface of the seafloor, unable to move above or below it.

Then, 541 million years ago, worm-like animals developed the first simple muscles. "That is what really changed the whole game," Ortega-Hernández told Live Science. The power to move helped the worms burrow down into the seafloor, bringing oxygen with them. "And all of a sudden, bam," Ortega-Hernández said. "We have these marine sediments which are just teeming with activity and life."

Moving above and below the seafloor's surface opened up new opportunities for animals to make a living. The early Cambrian period brought a rapid expansion of new life-forms as animals adapted to new habitats, food sources, predators and prey. This time — often referred to as the Cambrian explosion — gave rise to many lineages of animals that are still with us, including some of the first mollusks and arthropods.

"Many of these arthropods had almost teeth-like structures in the legs that they used for chewing [on] each other, and that started to become a real issue" for their victims, said Ortega-Hernández. In response, animals such as Wiwaxia evolved defensive armor, like spines and plates. Over millennia, this adaptive arms race only intensified. Animals became increasingly diverse, complex and extraordinarily weird-looking as they battled each other to survive.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Many Cambrian animals became extinct during the transition to the next geological period, the Ordovician. But some Cambrian curiosities are still with us today. Animals such as sponges, jellyfish and anemones look relatively similar to their Cambrian ancestors. And in 2014, Ortega-Hernández co-authored a study in the journal Nature providing evidence that Hallucigenia are related to modern-day velvet worms.

In some ways, finding Cambrian creatures weird is just a reflection of our contemporary bias, said Ortega-Hernández. The older an organism is, he explained, the more changes life on Earth has had to adapt to since the organism appeared. That means that the species we see today are naturally very different from those that lived 500 million years ago. In other words, Hallucigenia and Opabinia would probably think you look ridiculous, too.

Originally published on Live Science.