Mariner's Astrolabe from 1503 Shipwreck Is World's Oldest

A rare navigational tool has snagged a Guinness World Record as the oldest mariner's astrolabe.

The astrolabe dates to between 1496 and 1501; it sank to the bottom with a shipwreck in 1503 near the coast of the island of Al-Ḥallānīyah, in what is now Oman. The find is one of only 104 historical astrolabes in existence.

"It is a great privilege to find something so rare, something so historically important," David Mearns, an oceanographer at Blue Water Recovery, said in a 2017 statement after the astrolabe was first analyzed. Mearns, who led the archaeological excavation of the wreck, added, "It was like nothing else we had seen." [The 25 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth]

A maritime disaster

Mariner's astrolabes are circular devices that sailors used to measure the altitude of the sun or stars, which allowed them to calculate their ship's latitude. The instrument that was just inducted into the Guinness World Records was discovered under a layer of sand in the Arabian Sea in 2014. The astrolabe went down with a ship under the command of a Portuguese commander named Vicente Sodré, who was the uncle of the famous explorer Vasco da Gama.

Sodré and his brother, Brás Sodré, were commanding a subfleet of five ships in the 4th Portuguese India Armada in 1503. The two men were supposed to be patrolling off southwestern India, protecting a couple of trading outposts. Instead, the commanders went rogue and headed to the Gulf of Aden, where the officers and their men looted several Arab ships. The brothers then headed to Al-Ḥallānīyah and stopped to make some repairs. In May 1503, an enormous wind blew in, smashing two of the ships, the Esmeralda and the Sâo Pedro, into the rocks of the island. Vicente Sodré died in the wreck; Brás Sodré also died — on the island — although historical records do not provide the cause of death.

The disaster was famous because the ships went down laden with cargo and left Portugal's trading outposts open to an attack by Indian forces. In 1998, archaeologists surveyed the area where the ships were thought to have sunk and found what looked to be a wreck site. It wasn't until 2013, however, that the Oman government and researchers could arrange an excavation in the remote area. Over the next two years, archaeologists recovered almost 3,000 artifacts from the site, including a ship's bell inscribed with the year 1498.

Navigation by the stars

The astrolabe was found under 1.3 feet (0.4 meters) of sand in a natural gully near the wreck site. The artifact measures 6.9 inches (17.5 centimeters) in diameter and is festooned with the Portuguese coat of arms and an armillary sphere — a representation of the position of celestial objects around Earth. (The armillary sphere was a common Portuguese emblem and is still part of the country's flag.) The metal used in making the astrolabe is an alloy made mostly of copper, with a little zinc, tin and lead.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

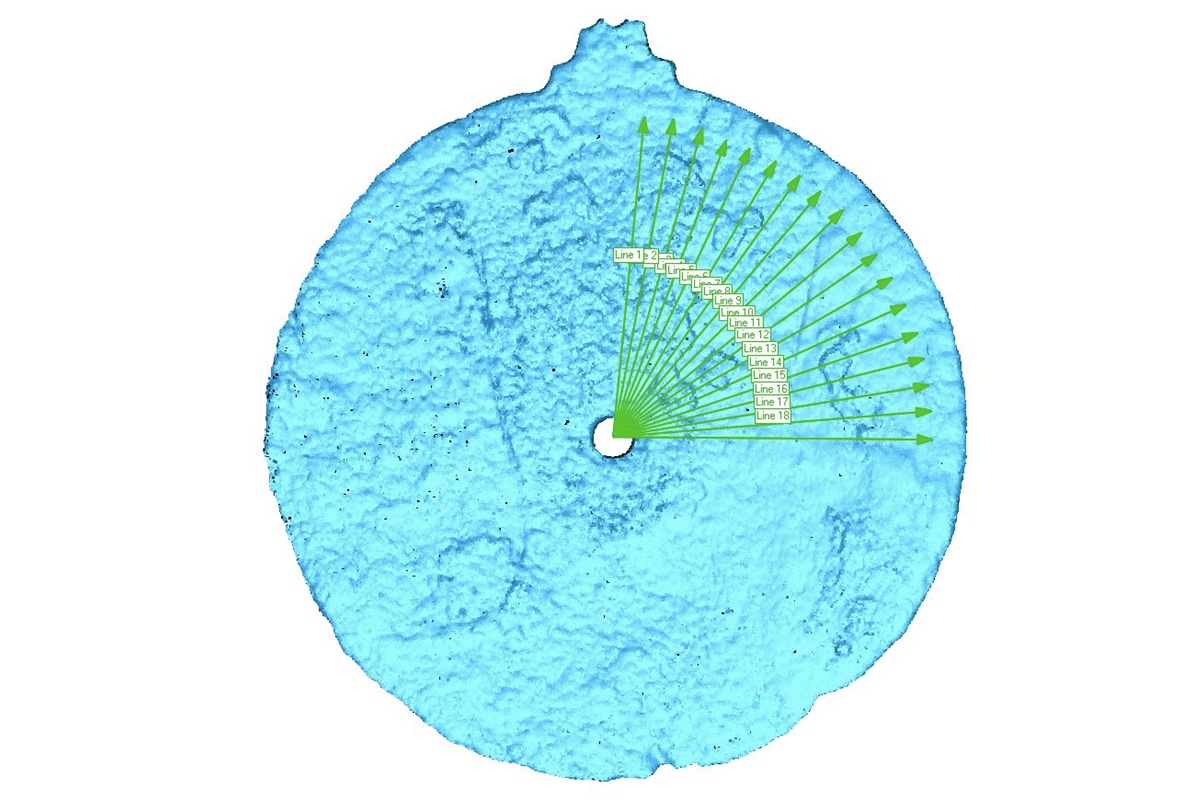

Years of damage by saltwater and tides erased most of the other markings on the astrolabe. To uncover what could no longer be seen by the naked eye, researchers at the University of Warwick in England used laser scanning to detect the tiniest grooves and etchings on the disk. Their results, published in the International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, revealed 18 scale marks on the upper right of the disk, which would have allowed the navigator to measure the angle of the sun or stars.

The first recorded use of an astrolabe was on an expedition by a Portuguese explorer in 1481, the researchers wrote, but the earliest versions were likely wood and did not survive the ages. The Sodré astrolabe had to be made before February 1502, when the squadron left Lisbon. The armillary sphere was an emblem of Dom Manuel I, the king of Portugal from late 1495 to 1521; the astrolabe was probably manufactured during his reign, at around 1496 at the earliest, the researchers concluded. The 1498 ship's bell and the dates of coins found at the wreck site all support that date range, they wrote.

According to the University of Warwick, that ship's bell will also be taking a place of honor in the Guinness World Records as the oldest ship's bell ever discovered.

- Photos: Ancient Greek Shipwreck Yields Antikythera Mechanism

- Image Gallery: World's Oldest Astrologer's Board

- The 20 Most Mysterious Shipwrecks Ever

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.