After a Bout of Flu, Mice Grow Taste Bud Cells in Their Lungs

A bout of influenza may have a long-lasting side effect: The growth of bizarrely out-of-place taste bud cells in the lungs.

New research conducted in mice finds that the growth of these taste bud cells may be linked to long-term problems with lung function after the flu, though additional research is needed to confirm the findings in humans.

Still, taste bud cells in the lungs "was just really weird to see, because the cells are not in the lung" normally, study author Andrew Vaughan, a biologist at the University of Pennsylvania's School of Veterinary Medicine, said in a statement. "The closest they are normally [found] is in the trachea." [11 Surprising Facts About the Respiratory System]

Rebuilding after the flu

Vaughan and his colleagues were studying the long-lasting impacts of severe lung inflammation caused by influenza A, one of the flu virus types responsible for the viral infection that circulates every winter. Around half a million people worldwide die from influenza A each year, Vaughan and his colleagues wrote in a paper published March 25 in the American Journal of Physiology – Lung, Cellular and Molecular Physiology. Many people who recover have long-lasting problems with lung function.

The researchers had previously found that this loss of lung function is likely related to the way the lungs rebuild themselves after sustaining severe damage from the infection. Certain cells called lineage-negative epithelial progenitors vastly expand their numbers in the lungs after the virus clears. They seem to help rebuild tissue, but many morph into abnormal cell types that can't do the typical job of exchanging oxygen and carbon dioxide across lung tissue.

In the new study, the researchers infected mice with H1N1, a type of influenza A. Then, the researchers euthanized the mice at different points during their recovery to study how their lung tissue had changed over time.

Out of place

They were unsurprised to find, post-infection, that the lungs were a hotspot of immune activity. What was odd, though, was that there was a strong "Type 2" immune response, which involves particular immune cells known to respond strongly to parasitic worms and to be involved in allergies — neither of which is involved with the flu.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

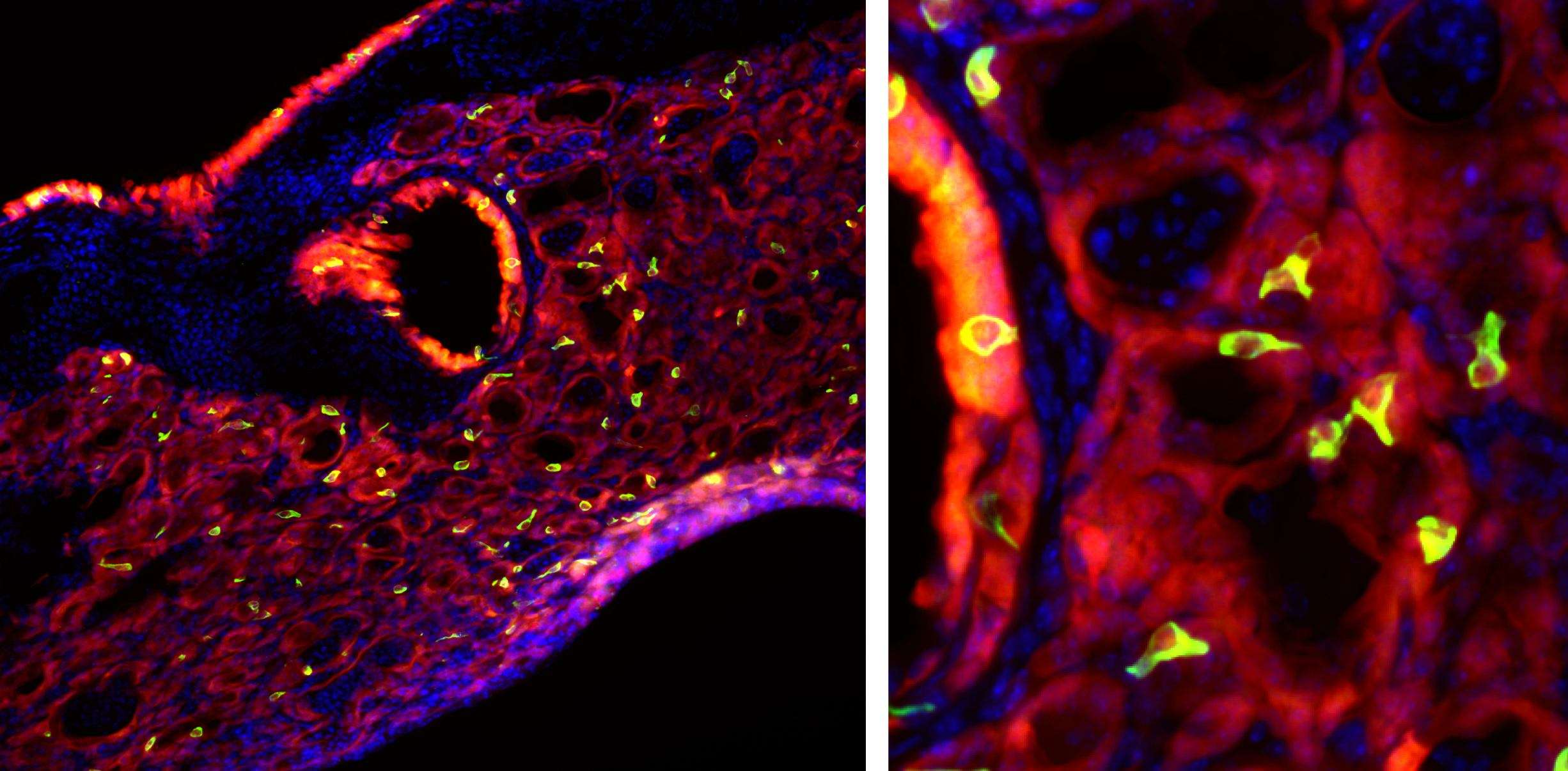

The researchers were perplexed by what might be creating this persistent immune response, so they set out looking for a particular type of cell known to cause it. These cells, called tuft cells, brush cells or solitary chemosensory cells, shouldn't be in the lungs. But in the post-flu mice, they were everywhere.

The cells are of the same sort found in taste buds, and they detect bitterness. When the researchers stimulated the out-of-place cells with bitter compounds, they went wild, growing and triggering an inflammatory response. The researchers also found that the out-of-place taste bud cells arose from the same lineage-negative epithelial progenitors already known to rebuild nonfunctional lung tissue after the flu.

This finding was exciting, Vaughan said, because solitary chemosensory cells are present in elevated numbers in people with asthma and in nasal polyps, which are noncancerous tissue growths in the nasal passage linked to inflammation.

"These recent findings may be a link between Type 2 inflammatory diseases, such as asthma, as well as nasal polyps, following a respiratory viral infection," Vaughan said in the statement. The finding could explain why children who get severe respiratory infections are predisposed to asthma later, he added. The researchers now plan to examine human lung samples to confirm that the same cells appear after the flu.

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.