How Scientists 3D Printed a Tiny Heart from Human Cells

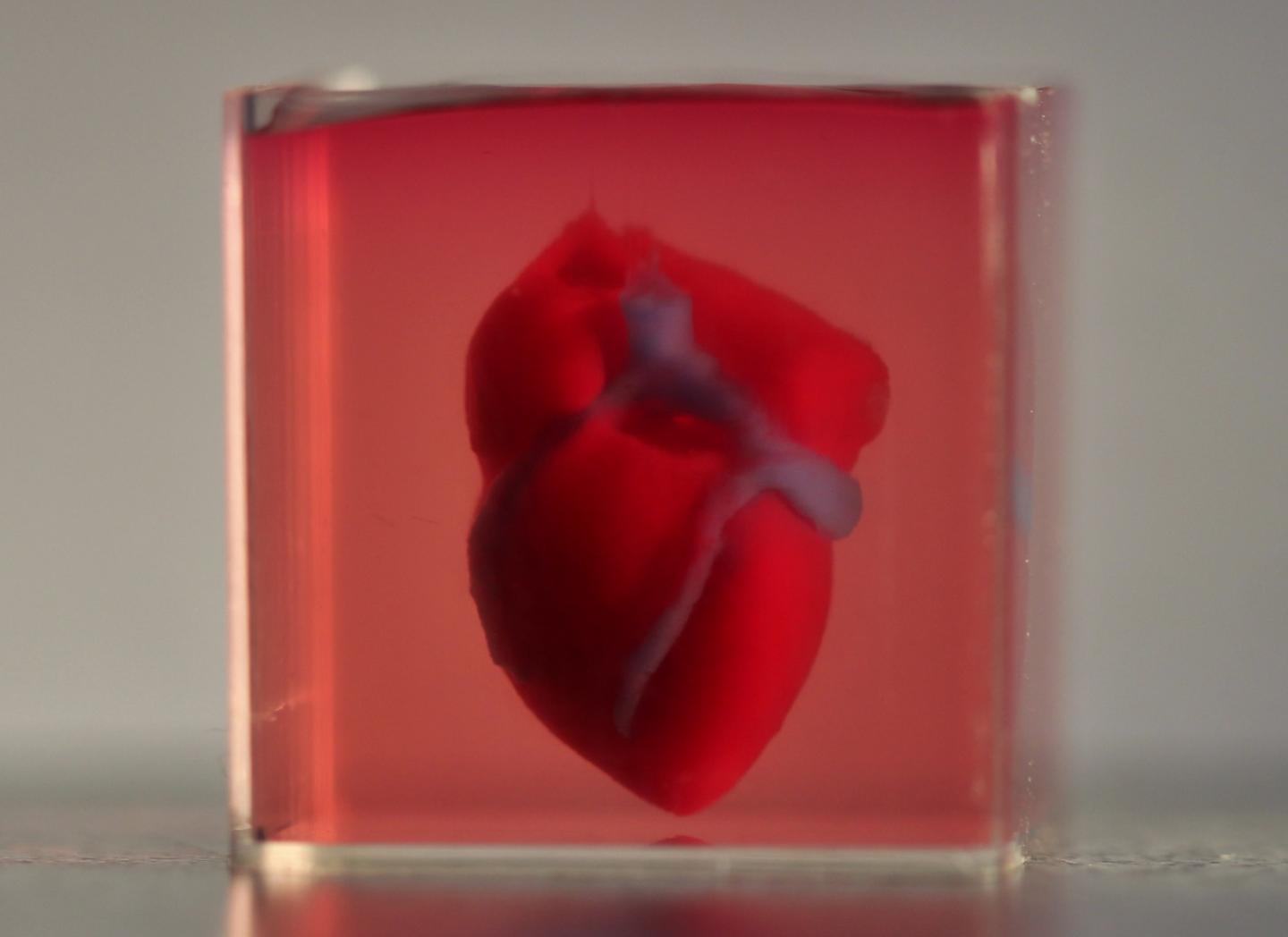

It has four chambers, blood vessels and it beats — sort of.

In a first, scientists have 3D printed a heart using human tissue. Though the heart is much smaller than a human's (it's only the size of a rabbit's), and there's still a long way to go until it functions like a normal heart, the proof-of-concept experiment could eventually lead to personalized organs or tissues that could be used in the human body, according to a study published Monday (April 15) in the journal Advanced Science.

To print the heart, researchers at Tel Aviv University in Israel began by taking a small sample of fatty tissue from a patient. In the lab, they separated this tissue into its component cells and the structure on which the cells sit, called the extracellular matrix. [7 Cool Uses of 3D Printing in Medicine]

Using genetic engineering, the scientists then tweaked the various components, reprogramming some of the cells to become cardiac muscle cells, or cardiomyocytes, and some to become cells that generate blood vessels.

The researchers then loaded these cells — serving as "bioinks" — into the printer, which had been programmed to print a heart, based on CT scans taken from the patient and an artist's depiction of a heart. The printer took between 3 and 4 hours to print the small heart with basic blood vessels. The researchers then incubated the heart and fed it oxygen and nutrients. Within a couple of days, the cells began to spontaneously beat.

But this beating wasn't quite like what a healthy human heart would do. "We need the cells to beat synchronically not just individually," said study co-author Assaf Shapira, the lab manager in the Laboratory for Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine at Tel Aviv University. In order for the heart to pump blood efficiently through the body, its cells need to beat in unison — something that the 3D-printed heart hasn't done yet. "Right now we're working to mature the tissue," Shapira said.

Eventually, a personalized 3D-printed heart might ease the shortage of transplant organs available to patients, and could also circumvent some of the risks associated with transplanting another person's organ — namely, that the body's immune system can reject these foreign tissues, Shapira told Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Camila Hochman Mendez, the assistant director of organ, repair and regeneration research labs at the Texas Heart Institute who was not a part of the study, said that the new findings are "really innovative and move the field forward" by demonstrating that something more complex than a single wall of the heart can be printed. But the results also "show all the hurdles that the field is still facing," she added.

In order to print a full-size, fully functioning heart, the scientists would need to print a higher-resolution organ — one with much more vasculature that could carry oxygen and nutrients through it, Hochman Mendez told Live Science. But doing this would require months of printing — a timespan during which the cells would not survive.

The researchers underscored that the tiny heart is still a "proof-of-concept," but that they hope to figure out a way to create more dense vasculature in the future.

"Of course, if we would need to fabricate a larger heart, it would be expensive, it would take much more time to print and much more material would need to be extracted from the patient," Shapira said.

Indeed, there's still much more research needed before it becomes commonplace to simply hit "print" on the 3D printer at the doctor's office.

- The 10 Weirdest Things Created By 3D Printing

- 7 Foods Your Heart Will Hate

- 15 Odd Things That Can Be 3D Printed

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.