This Ancient 'Warg' Was Scarier Than a Tolkien Beast, Terrorized Kenya 22 Million Years Ago

In the "Lord of the Rings" series, author J.R.R. Tolkien invented the fantastical "warg," a wolf-like beast with sharp teeth that lived in the Misty Mountains. Little did Tolkien know that such a creature, perhaps one even more terrifying than a warg, actually existed.

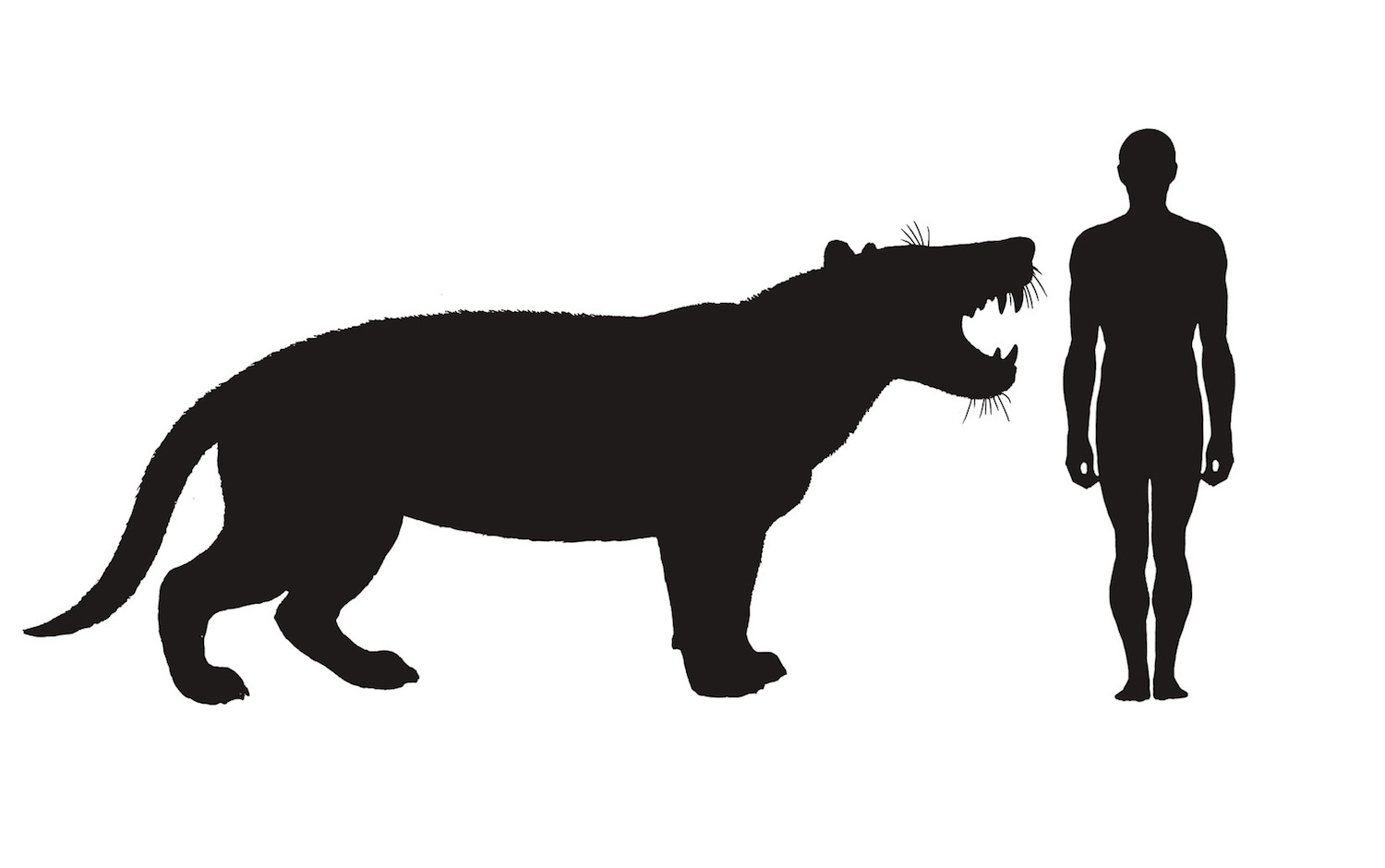

This newly discovered but now extinct carnivore lived about 22 million years ago in what is now Kenya. It was larger than a polar bear, the largest land-based carnivore alive today; it weighed up to 3,300 lbs. (1,500 kilograms), measured 8 feet (2.4 meters) long from snout to rump and stood 4 feet (1.2 m) tall at its shoulders.

The creature had very sharp, powerful teeth, and is considered a hypercarnivore — meaning it got almost all its calories from meat. [Image Gallery: 25 Amazing Ancient Beasts]

Researchers are calling the newfound meat eater Simbakubwa kutokaafrika, Swahili for "big lion from Africa." But it was much larger than a modern lion, said study co-researcher Matt Borths, curator of the Division of Fossil Primates at the Duke Lemur Center in North Carolina.

"Part of the reason we named it 'big lion' in Swahili is because it would have played a lion-like role in its ancient ecosystem," Borths told Live Science in an email. When it was hungry, S. kutokaafrika didn't hold back. "Animals that might have been on the menu were anthracotheres (hippo relatives that were lankier than their modern cousins), elephant relatives and giant hyraxes (today, hyraxes look like grumpy rabbits, but in the past they filled zebra and antelope niches in Africa)."

Besides looking like a warg, S. kutokaafrika would seem weird by today's standards, Borths said.

"Compared to modern carnivorous mammals, its head would have looked a little too big for its body, like a very toothy Funko Pop figure," he said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Borths came across the fossil remains of S. kutokaafrika in a museum drawer. He happened to be at the Nairobi National Museum, where he was studying the evolution of hyaenodonts, a group of extinct carnivorous mammals that lived in Africa, Eurasia and North America during the Miocene epoch, which lasted from about 23 million to 5 million years ago.

"I thought I had gone through all the meat-eaters from about 20 million years ago," Borths said. "Then, during a lunch break, I decided to open a few other drawers to learn about carnivores from the [last] ice age, and there was this enormous jaw. Based on the structure of the teeth, I knew it was a hyaenodont, but I had no idea this specimen existed."

The jaw was so large, it couldn't fit into the cabinet with its close relatives, he said. Keen to learn more, he reached out to Nancy Stevens, who was studying fossils from Meswa Bridge, Kenya, where S. kutokaafrika's remains were originally found. Stevens, a professor of functional morphology and vertebrate paleontology at Ohio University, became the co-author on the study.

"Discoveries like this one underscore the importance of museums as troves of information about our planet's past," Stevens told Live Science in an email.

In addition to the excitement of finding such a large and previously unknown hypercarnivore, the researchers said they were happy to find such a complete hyaenodont.

"Most of the relatives of Simbakubwa are known from pretty scrappy material," Borths said. "The teeth are still pretty sharp! We also have an ankle bone that tells us how Simbakubwa might have moved. With these data, researchers can better interpret fragmentary material of other species, piecing together the evolution of this group of giant carnivores that evolved as continents slammed into each other, landscapes became more open and lineages that originated on different continents started to mix for the first time."

The new study was published online today (April 18) in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

- Top 10 Deadliest Animals (Photos)

- Photos: Fearsome Ancient Otter Was As Large As a Wolf

- Images of an Ancient Hippo Ancestor

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.