Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Life may have arisen in our solar system before Earth even finished forming.

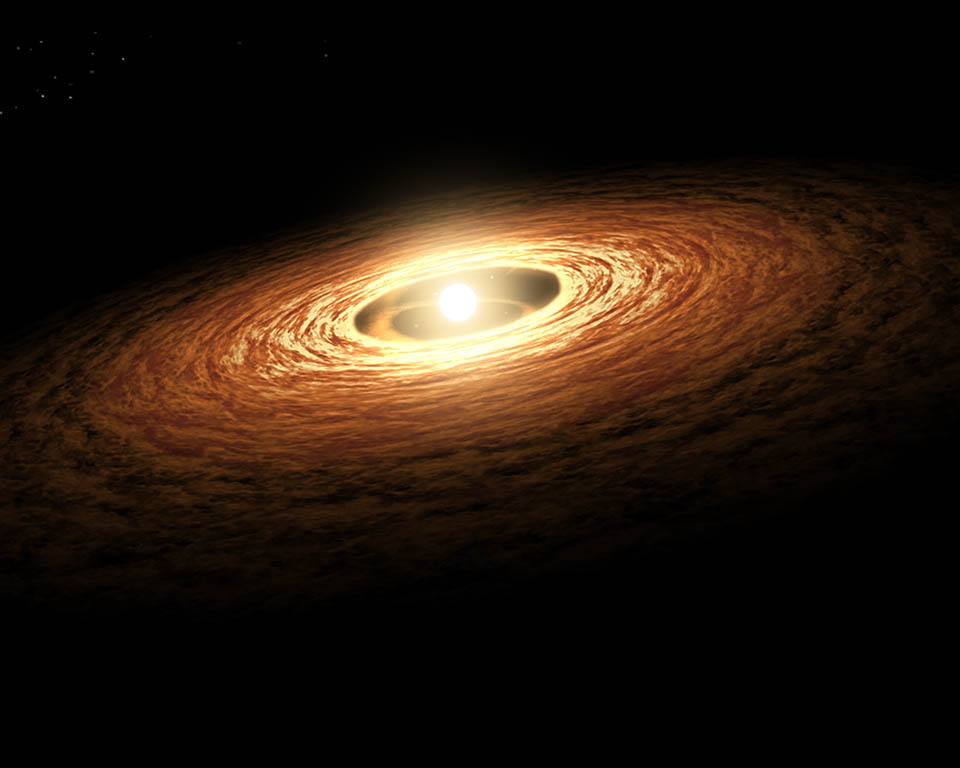

Planetesimals, the rocky building blocks of planets, likely had all the ingredients necessary for life as we know it way back at the dawn of the solar system, said Lindy Elkins-Tanton, a planetary scientist at Arizona State University (ASU).

And clement conditions may have persisted inside some planetesimals for tens of millions of years — perhaps long enough for life to emerge, said Elkins-Tanton, the director of ASU's School of Earth and Space Exploration and the principal investigator of NASA's upcoming mission to the odd metallic asteroid Psyche.

Article continues belowRelated: 7 Theories on the Origin of Life

Some planetesimals survived into and beyond the planet-forming period, raising the possibility that one of these primitive bodies may have seeded Earth with life, she added.

"Not all planetesimals are going to be involved in the kinds of catastrophic collisions that would cause them to go into a plasma or otherwise completely denature anything that was created," Elkins-Tanton said April 11 at the Breakthrough Discuss conference at the University of California, Berkeley.

"Some things are going to fall — like Chelyabinsk, for example — back onto the surface of a temperate planet," she added, referring to the 65-foot-wide (20 meters) object that exploded over the Russian city of Chelyabinsk in February 2013. "So, there is that possibility in the end."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Elkins-Tanton said this basic idea grew out of a course she taught at ASU in the fall of 2016. At the beginning of the semester, she asked the students to consider whether life could have arisen on small bodies. Over the next few months, the students, Elkins-Tanton and her co-author on the newly presented work, Stephen West, explored this possibility, as well as a number of other questions that stemmed from that core question.

Life as we know it requires three main ingredients: liquid water, organic molecules and an energy source. Planetesimals, which formed within 1.5 million years of the solar system's birth, likely featured all three, Elkins-Tanton said.

For example, more than 35 different amino acids have been identified in the Murchison meteorite, an ancient space rock that fell to Earth in southern Australia in 1969.

Murchison is so full of organics that it "smells like an oil well," Elkins-Tanton said. "What could be a better place for the advent of life than a nice, warm, wet piece of Murchison? So, that's the idea that we're starting with."

The energy source on early planetesimals, such as Murchison's parent body, came from the radioactive decay of aluminum-26, she explained. The heat flowing through some planetesimals' interiors was intense enough to melt the objects completely, which is certainly not conducive to the emergence of life.

But other bodies would have melted only partially, from the inside out, so they would eventually sport a metallic core, a magma-ocean mantle and a rocky, primitive crust. Such planetesimals would have had extremely hot interiors but frigid surfaces, Elkins-Tanton said. Waves of heat radiating from the depths would have spurred the release of fluids such as liquid water, driving that material up toward the surface.

Such processes may have created habitable environments beneath the planetesimals' rocky surfaces. And these environments likely lasted for relatively long stretches.

For example, modeling work performed by Elkins-Tanton and West, who's now at the California-based company Metis Technology Solutions, suggests that small planetesimals — those up to 30 miles (50 kilometers) wide — could have supported liquid water underground for about 15 million years.

And an earlier study Elkins-Tanton conducted with Ben Weiss and Maria Zuber of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology found that larger bodies could have remained wet for even longer — perhaps 50 million years or so.

It's unclear if this window is long enough for life to get going, Elkins-Tanton stressed. That's because we don't know how long that window has to be. "I'm going to bravely assert that we really have no idea," she said.

For example, the earliest unambiguous signs of life on our 4.5-billion-year-old Earth date to about 3.8 billion years ago. But some scientists have presented evidence that microbes already had a foothold here by 4.1 billion years ago. And at this same Breakthrough Discuss meeting, biochemist Steven Benner of the Foundation for Applied Molecular Evolution in Florida argued that life actually emerged 4.36 billion years ago. (Only at that time was Earth's atmospheric chemistry right for the first organisms, RNA-based microbes, to evolve, Benner said in his talk.)

To be clear, Elkins-Tanton and West aren't arguing that Earth life actually did originate on planetary building blocks — just that this idea is worthy of consideration. And the new work is preliminary; the Breakthrough Discuss talk marked the first time Elkins-Tanton formally presented the idea to her planetary-science colleagues.

She said she hopes the work spurs further discussion and research about the origin of life and its possible dispersal throughout the solar system.

"This is meant to be just a kind of a thought problem for us all to consider," Elkins-Tanton said. "Could life actually have arisen on planetesimals? Could there be evidence for life in meteorites that we have not known to look for? And if this is so, how could they have been spread through the solar system — and many, many unanswerable implications of that possibility."

The idea that life has spread from body to body throughout the solar system is not a new one, of course. For example, Benner and others have suggested that Earth life may actually have originated on Mars and traveled here aboard a rock liberated from the Red Planet by an asteroid or comet strike.

And some researchers have even posited that life may have come to Earth from another star system, perhaps aboard a wandering comet.

- Earth Quiz: Do You Really Know Your Planet?

- Moon-Forming Smashup May Have Paved the Way for Life on Earth

- Life Among the Stars? Tiny Interstellar Probes May Test 'Panspermia' Idea

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), is out now. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus