Mystery of Weird Sky-Glow Named 'STEVE' Finally Solved

Three years ago, a mysterious purplish glow arced across the Canadian skies. The light show was a completely unknown celestial phenomenon, so it was given a name befitting its beauty and grandeur: Steve.

Now, scientists have finally pinpointed what causes the phenomenon's glowing ribbons of reddish purple and green: magnetic waves, winds of hot plasma and showers of electrons in regions they normally never appear.

A brief history of STEVE

On July 25, 2016, observers noticed an odd type of atmospheric light display illuminating the night sky in the Northern Hemisphere. They quickly realized that this was no ordinary aurora and gave it a new name inspired by the film "Over the Hedge" (DreamWorks Animation, 2006); a group of forest animals, confounded by a hedge for the first time, name the unfamiliar object "Steve." (Astronomers later changed that name to STEVE, an acronym for strong thermal emission velocity enhancement.)

Preliminary analysis of STEVE found that its optical effects came about differently than an aurora's, but scientists couldn't say what exactly was taking place. [Northern Lights: 8 Dazzling Facts About Auroras]

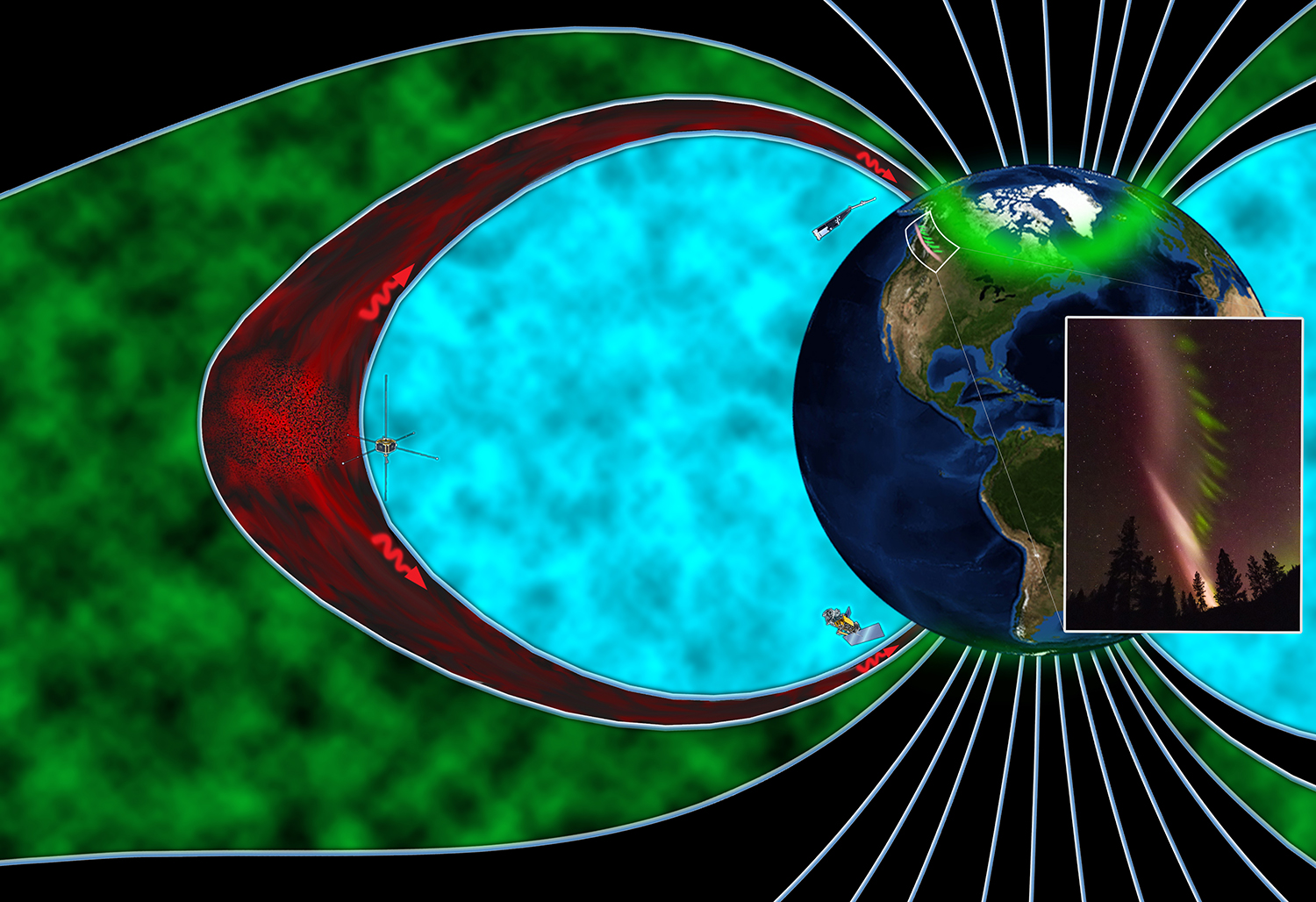

Auroras can trace their origins to the sun, when sunspots spit out clouds of protons and electrons that speed toward Earth on solar winds. Once these charged particles reach the planet, its magnetic field draws them toward the North and South poles. As the particles leave the magnetosphere and bombard the planet's upper atmosphere, they interact with elements such as oxygen and nitrogen to generate swirling ribbons of light.

But STEVE's light shows are different from a typical aurora's. STEVE appears farther south, and over more-populated areas, than most auroras do. And unlike an aurora and its trademark greenish swirls that undulate horizontally, STEVE produces a towering vertical purplish or green band, sometimes accompanied by a column of short bars resembling a picket fence, according to the new study.

"Completely unknown"

In a prior study published in 2018, the same researchers found that STEVE originated in the ionosphere, the zone stretching from about 50 to 375 miles (80 to 600 kilometers) above the ground, where auroras form.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But even though STEVE appeared during the same solar-powered magnetic storms that produced auroras, most of the newfound phenomenon's glowing appearance was not the result of charged particles slamming into Earth's upper atmosphere. That conclusion comes from evidence gathered by satellites that passed through a STEVE event in 2008.

The new study used that 2008 data, along with satellite data and ground observations from two other STEVE events, to identify two different processes that shape STEVE's light ribbon and picket fence.

STEVE's vertical ribbons are illuminated not by a rain of charged particles falling into the atmosphere, but by friction caused by hot plasma flows and powerful magnetic waves about 15,000 miles (25,000 km) above Earth, according to the study. Heat from these flows energizes particles so that they generate purple light, a mechanism similar to the illumination of incandescent lightbulbs.

While aurora glows occur when electrons and protons fall into Earth's atmosphere, "the STEVE atmospheric glow comes from heating without particle precipitation," study co-author Bea Gallardo-Lacourt, a space physicist at the University of Calgary in Canada, said in a statement.

STEVE's green picket fence, on the other hand, forms as auroras do: when electrons rain down on the upper atmosphere. However, this occurs far south of the latitudes where auroras usually form, "so it's indeed unique," Gallardo-Lacourt said.

This distinctive picket fence also appeared in skies over the Northern and Southern hemispheres at the same time, the authors wrote. This demonstrates that the energy source fueling STEVE is abundant enough to create simultaneous light shows in both hemispheres, the study authors said.

But scientists still don’t know why the phenomenon appears so much farther south than auroras do, meaning that STEVE retains a little of its mystery.

The findings were published online April 16 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

- Aurora Photos: Northern Lights Dazzle in Night-Sky Images

- Aurora Borealis: What Causes the Northern Lights and Where to See Them

- Aurora Photos: See Breathtaking Views of the Northern Lights

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.