Russians Likely Used This Beluga Whale As a Spy. Here's Why.

Fishermen in Norway came across a Russian spy late last week, but the interloper wouldn't reveal its mission, and with good reason: It couldn't, because it was a beluga whale (Delphinapterus leucas).

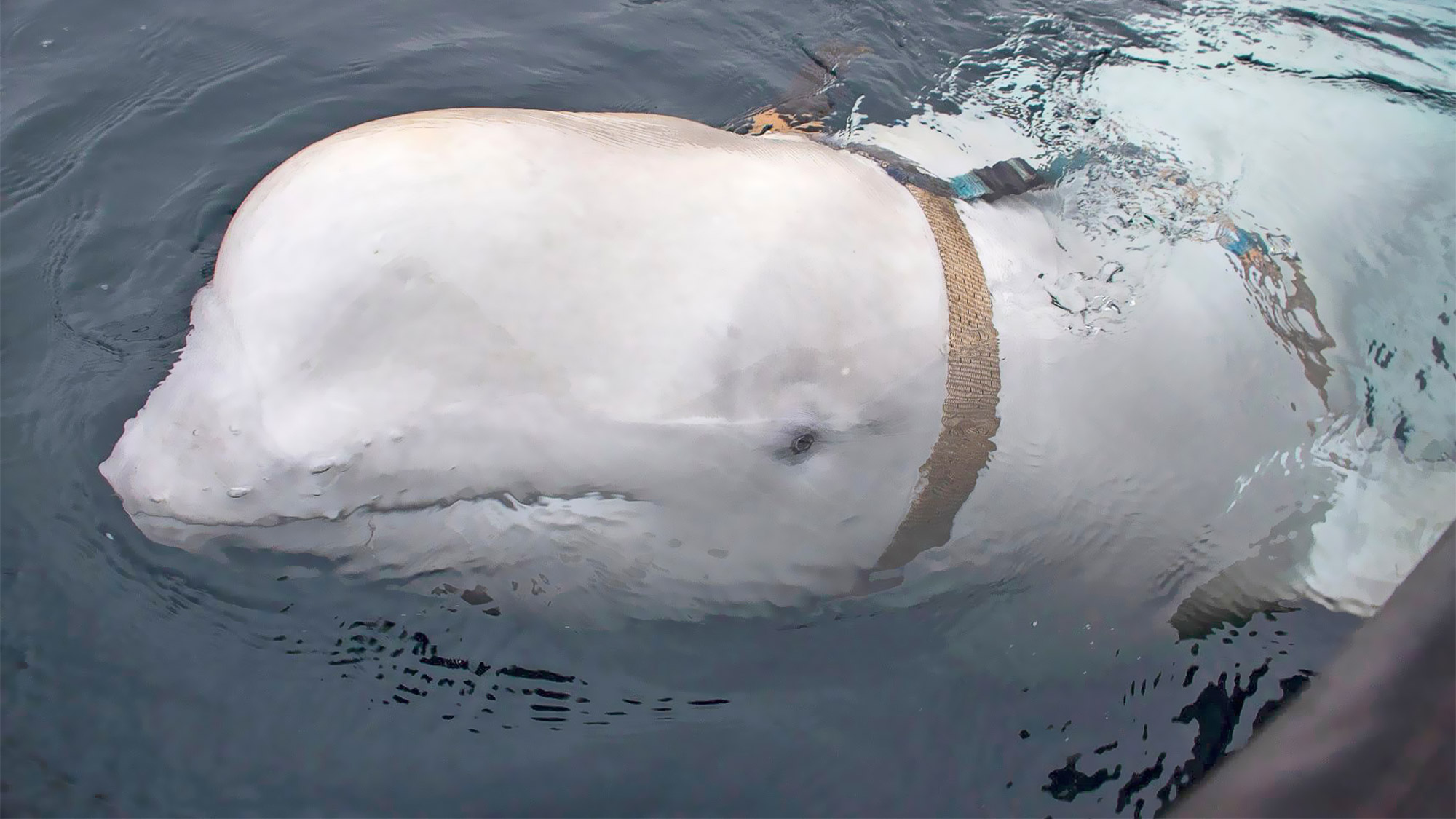

However, the beluga whale's outfit gave it away. The surprisingly tame whale was wearing a harness that read "Equipment of St. Petersburg," indicating that it was likely trained by the Russian navy to be used for special operations, according to news sources.

But why would the Russian navy use a beluga whale for special ops — as opposed to a bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) or a California sea lion (Zalophus californianus), like the U.S. Navy does? Here's a look at why these marine mammals are drafted into service by some countries. [Beasts in Battle: 15 Amazing Animal Recruits in War]

The short answer is that beluga whales are extremely intelligent, calm in difficult situations and easily trainable, said Pierre Béland, a research scientist in marine biology at the St. Lawrence National Institute of Ecotoxicology in Montreal, Canada. Béland has been studying belugas since 1982, but he wasn't involved with this whale's case.

Norweigan fisherman spotted the beluga near the fishing village of Inga, along the northern coast of Norway on April 26. Later, Norweigan scientists tracked down the whale and removed its very tight harness, according to the Norweigan news outlet VG. The harness had an attachment for a GoPro camera, but there wasn't a camera there anymore, Audun Rikardsen, a professor at The Arctic University of Norway in Tromsø (UiT), told VG.

Rikardsen added that as far as he knows, neither Norweigan nor Russian researchers put harnesses on belugas, which suggests that this was likely the handiwork of the Russian navy in Murmansk, a city in northwestern Russia, he said. The animal probably approached the fishermen's boat because the animal was used to people feeding it fishy treats, Rikardsen noted. He said that he hoped the whale would be able to hunt for food on its own, but that's still unclear at this point, Rikardsen said.

Beluga in Turkey

This isn't the first case of a Russian-trained beluga going AWOL. In the mid-1990s, Béland got a call from government officials in Turkey, asking if it was normal for a beluga whale to be in the Black Sea. "I said, 'No, not at all,'" Béland told Live Science. These animals live in the Arctic and aren't typically found in warmer waters.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Béland flew to Turkey, where he saw the whale with his own eyes, swimming off the country's northern coast. "It was tame, it would come to us and you could give him fish and pat him on the head," Béland recalled. He also noticed something curious: The whale's teeth had been filed down flat.

"It turned out [the beluga] was coming from a naval facility on the Russian side in the Crimea," Béland said. "We surmised they had filed its teeth so it could take a big object in its mouth, such as a magnetic mine that it could stick on the hull of a foreign ship for military purposes."

Béland later learned that a storm had ripped a net at this naval facility, allowing the beluga whale to escape. But the Russians found out; they parked their ship within international waters and someone, presumably the whale's trainer, was able to call the whale back. A year later, the whale escaped to Turkish waters again. By this time, the whale had quite a fan base in Turkey. But, once again, the Russians returned and collected the mammal, "and I never saw it again," Béland said. [Photos: See the World's Cutest Sea Creatures]

Naval service

Even the U.S. Navy has studied beluga whales, though with the purpose of learning how the animal's sonar could help scientists improve the sonar on submarines, Béland said.

The U.S. Navy doesn't appear to use beluga whales anymore; it's not clear why, but one reason could be water temperature. While the Navy has animal training facilities in California and Hawaii, both places are too warm for the Arctic animal, he said.

That said, it's no wonder that colder-climate countries such as Russia continue to train belugas. Naval sources from different countries have said that "beluga whales were far easier to train than dolphins," Béland said. "Maybe because dolphins are like a 3-year-old child — they don't have a very long attention span, they are temperamental. Whereas belugas are calmer."

Evolution likely plays a role in the beluga's temperament. Take, for instance, the beluga's icy home in the Arctic. If there were a dolphin and a beluga trapped under the ice, both would need to find an ice-free area where they could surface to breathe. "Dolphins would go in one direction and find there's no open water and come back and get frantic about it," Béland said. "But beluga whales have learned through selection or cultural evolution to sit there and listen, send sounds left and right and find out where the nearest open water is and then go there."

Moreover, like dolphins, belugas are smart. They can even mimic the rhythm and frequency of human speech, a 2012 study found. They're also deep divers, going as far as 3,280 feet (1,000 meters) underwater, Béland said.

"They're very social, very adept, very intelligent, very inquisitive," Uko Gorter, the president of the American Cetacean Society, told Live Science.

It's unclear how this particular whale ended up in Norway. It's possible it escaped from its facility, or maybe it just took a break from a mission, perhaps a reconnaissance patrol it was doing, Béland said. But regardless of what happened, it's a shame that a wild animal was trained for naval purposes, he said.

"I understand that we need them at some point because other countries, which are not necessarily friendly, have them. But I think we should leave animals out of it," Béland said.

- In Photos: Response Teams Try To Save Starving Killer Whale

- Humpback Whale Rescue Photos

- Image Gallery: Mysterious Lives of Whale Sharks

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.