Oldest Human Footprint in Americas May Be This 15,600-Year-Old Mark in Chile

The earliest human footprint on record in the Americas wasn't found in Canada, the United States or even Mexico; it was found much farther south, in Chile, and it dates to an astonishing 15,600 years ago, a new study finds.

The finding sheds light on when humans first reached the Americas, likely by traveling across the Bering Strait land bridge in the midst of the last ice age.

This 10.2-inch-long (26 centimeters) print might even be evidence of pre-Clovis people in South America, the group that came before the Clovis, which are known for their distinctive spearheads, the researchers said. The find suggests that pre-Clovis people were in northern Patagonia (a region of South America) for some time, as the footprint is older than archaeological evidence from Chile's Monte Verde, a site about 60 miles (100 kilometers) south containing artifacts that are at least 14,500 years old. [10 Things We Learned About the First Americans in 2018]

Vertebrate paleontologist Leonora Salvadores discovered the footprint in December 2010, when she was an undergraduate student at the Austral University of Chile. At the time, Salvadores and her fellow students were investigating a well-known archaeological site known as Pilauco, which is about 500 miles (820 km) south of Santiago, Chile.

However, it took years for study lead researcher and paleontologist Karen Moreno and study lead investigator and geologist Mario Pino, both at the Austral University of Chile, to verify that the print was human, radiocarbon date it (they tested six different organic remnants found at that layer to be sure) and determine how it was made by a barefoot adult.

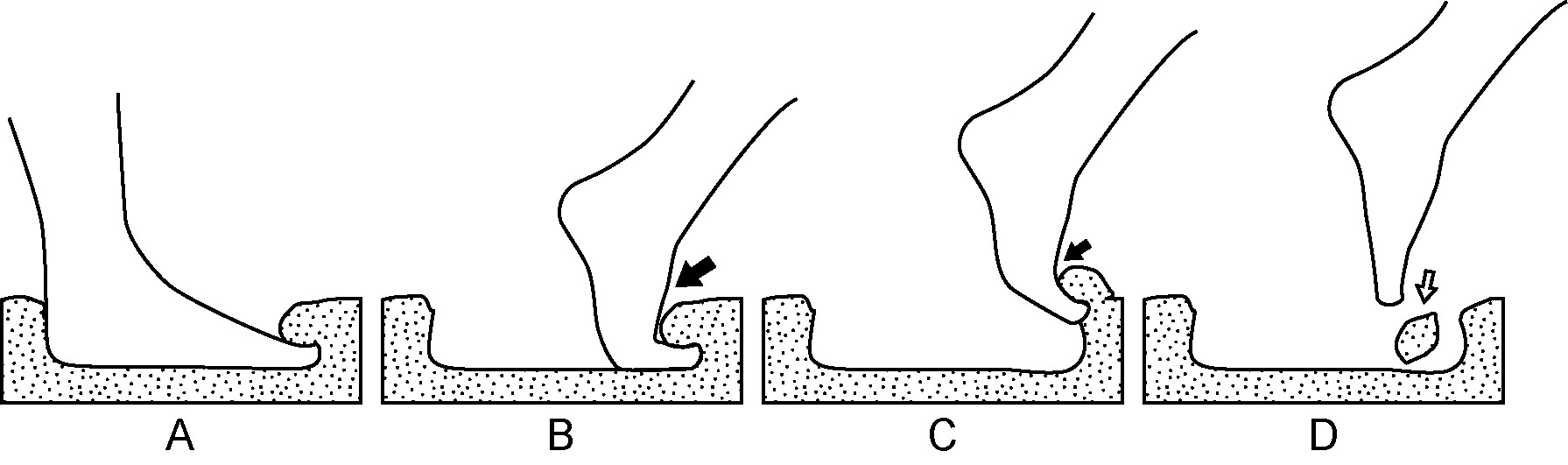

Part of these tests involved walking through similar sediment to see what kinds of tracks got left behind. These experiments revealed that the ancient human likely weighed about 155 lbs. (70 kilograms) and that the soil was quite wet and sticky when the print was made. It appears that a clump of this sticky dirt clung to the person's toes and then fell into the print when the foot was lifted, as the image below suggests.

The footprint is classified as a type called Hominipes modernus, a footprint usually made by Homo sapiens, the researchers said. (Just like species, trace fossils, such as footprints, receive scientific names.) Previous excavations at the site revealed other late Pleistocene fossils, including the bones of elephant relatives, llama relatives and ancient horses, as well as rocks that humans may have used as tools, the researchers said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The study "adds to a growing body of fossil and archaeological evidence suggesting that humans dispersed throughout the Americas earlier than many people have previously thought," said Kevin Hatala, an assistant professor of biology at Chatham University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, who was not involved with the study.

This find comes a mere year after the discovery of the oldest known human footprints in North America, which date to 13,000 years ago, Hatala noted.

It would be nice to have more data from the Chile site — "more footprints, more artifacts, more skeletal material and so on," Hatala told Live Science in an email. "But unfortunately, the fossil and archaeological records are never as generous as we'd like! With just a single human footprint to work with, the authors extracted as much information as they could. When we look at this evidence in the context of other data, it makes a strong case for the antiquity of [the] human presence in Patagonia."

The footprint is now preserved in a glass box and is housed at the recently established Pleistocene Museum in the city of Osorno, Chile. The study was published online April 24 in the journal PLOS One.

- In Photos: Stone Age Human Footprints Discovered

- Photos: These Animals Used to Be Giants

- Photos: Human Footprints Help Date Ancient Tibetan Site

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.