15 people were brutally murdered 5,000 years ago, but the bodies were buried with care

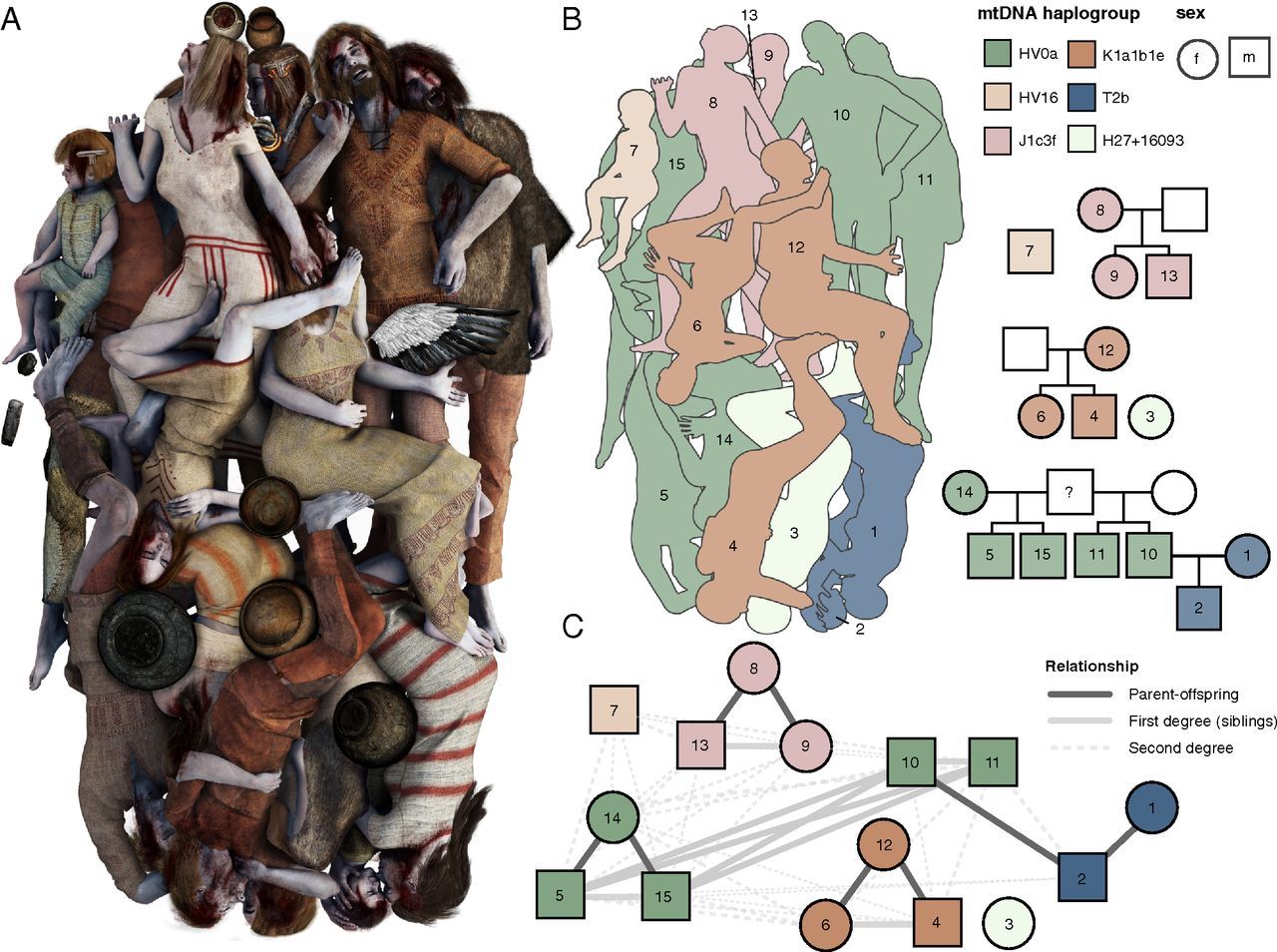

An extended family met a grim end when 15 of them were brutally murdered about 5,000 years ago in what is now Poland. But whoever buried these victims did so with care, placing mothers next to children and siblings side by side.

An extended family met a grim end when 15 of them were brutally murdered — killed by vicious blows to the head — about 5,000 years ago in what is now Poland. But though these victims were violently killed, whoever buried them did so with care, placing mothers next to children and siblings side by side, a new study shows.

In other words, the placement of bodies in this burial was far from random.

The burial shows "kids next to parents, brothers next to each other [and the] oldest person close to center," said study co-lead researcher Niels Nørkjær Johannsen, a professor in the Department of Archaeology and Heritage Studies at Aarhus University, in Denmark. [25 Grisly Archaeological Discoveries]

Archaeologists learned about the late Neolithic burial during the construction of a sewage system in 2011, near the town of Koszyce in southern Poland.

This is far from the first large grave filled with ruthlessly murdered victims from the Neolithic; the remains of nine brutally murdered people dating to 7,000 years ago are buried in Halberstadt, Germany, and 26 murdered individuals are buried in a 7,000-year-old "death pit" at Schöneck-Kilianstädten, Germany. But the newly described burial is unique, because the individuals were related to one another and weren't buried haphazardly, according to a genetic analysis on the remains.

"We are dealing with what you might call an extended family," Johannsen told Live Science in an email. "We were able to show that there are four nuclear families present and emphasized in the burial, but these individuals are also related to one another across these nuclear families — for example, being cousins."

The genetic analysis also revealed that the group, which was part of the Globular Amphora culture (named for their globular-shaped pots), had one male lineage and six female lineages, "indicating that the women were marrying from neighboring groups into this community where the males were closely related," Johannsen noted.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

It's impossible to know who buried the victims, but whoever did wasn't a stranger. "It is clear that lots of effort has gone into this [burial] and the people who buried them knew the deceased very well," Johannsen said.

Even so, it's interesting that these 15 people were buried together, rather than separately.

"Perhaps the people who buried them were in a hurry?" Johannsen said. "But they nonetheless took care to bury individuals next to their closest family and also equipped the dead with funerary gifts, such as ceramic amphorae [jugs], flint tools, amber and bone ornaments."

The burial doesn't hold the remains of any of the family's fathers, so maybe the victims were massacred when the fathers were away, Johannsen said. "[Perhaps] they returned later, found their families brutally killed and subsequently buried their families in a respectful way."

The massacre is tragic, but unsurprising given the time period. During the late Neolithic, European cultures were being heavily transformed by groups migrating from the steppes, to the east. "We do not know who was responsible for this massacre, but it is easy to imagine that the demographic and cultural turmoil of this period somehow precipitated violent territorial clashes," Johannsen said. [Fight, Fight, Fight: The History of Human Aggression]

The finding is remarkably similar to 4,600-year-old burials from the Corded Ware culture (named for their corded pottery designs) found near Eulau, Germany. At that site, "violently killed people were also carefully buried according to their familial relationships," said Christian Meyer, a researcher at OsteoARC, Germany, who was not involved in the study but who has worked on several other sites of Neolithic mass violence.

If anything, the Koszyce burial "is further evidence that lethal mass-violence events occurred at times throughout the Neolithic of Europe," Meyer said. "These events could be catastrophic for the targeted communities, which were apparently built upon overlapping social and biological kinship ties."

However, while the researchers of the new study call the Koszyce finding a "mass grave," Meyer said he sees it differently. "The people were buried very carefully, received grave goods and were positioned according to their immediate kinship ties," he said. "We should maybe call this a large 'multiple burial' rather than a 'mass grave,'" in which bodies are typically buried in a disorganized heap.

The study was published online May 6 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

- Photos: 5,000-Year-Old Neolithic Figurine

- In Photos: Ireland's Newgrange Passage Tomb and Henge

- In Photos: Intricately Carved Stone Balls Puzzle Archaeologists

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.