Humans Crawled Through a Cave 14,000 Years Ago. We Can Still See Their Perfectly Preserved Footprints.

To light their way, these late Stone Age people likely burned bundles of pine (Pinus) sticks, which archaeologists also found in the cave, known as Grotta della Bàsura, in northern Italy.

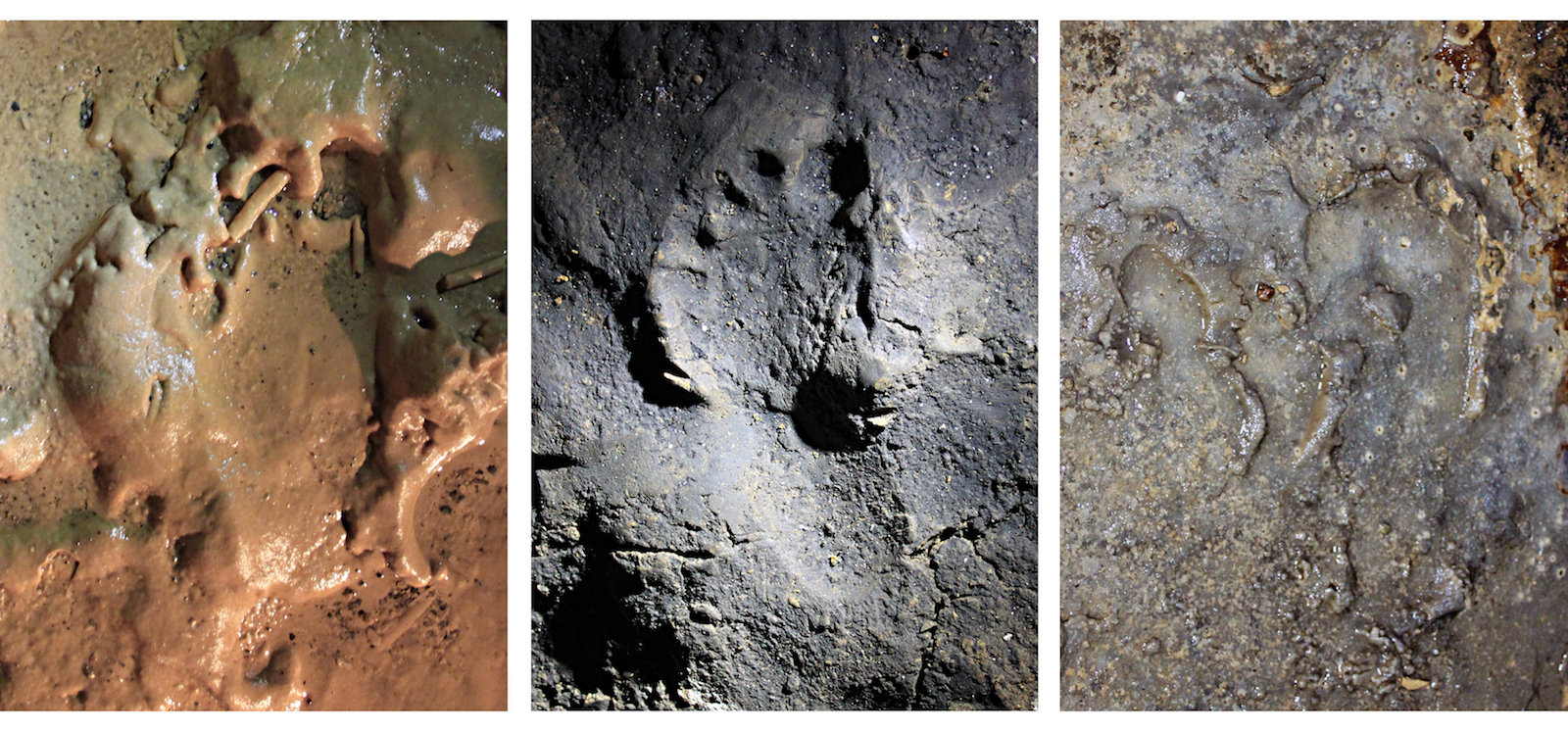

The cave's ceiling was so low, that at one part, the ancient explorers were forced to crawl, leaving behind "the first evidence ever of human footprints left during crawling locomotion," that is, in a "crouching walk" position, said study first author Marco Romano, a postdoctoral researcher at the Evolutionary Studies Institute at the University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa. [In Photos: Stone Age Human Footprints Discovered]

Researchers have known about the ancient human presence in Grotta della Bàsura since the 1950s. But the new analysis is the first high-tech look at these particular trackways, in which the researchers used laser scans, sediment analysis, geochemistry, archaeobotany and 3D modeling to study the prints.

There were so many prints — 180 in all — that the researchers were able to piece together what happened that day during the upper Paleolithic (also known as the late Stone Age). According to the different sizes of footprints, it appears there were five people: a 3-year-old, 6-year-old, a pre-adolescent (8- to 11-year-old) and two adults, the researchers found.

This group was barefoot and didn't appear to be wearing any clothes (at least not that left any imprints in the cave). After walking nearly 500 feet (150 meters) into the cave, the party arrived at the "Corridoio delle Impronte" (footprint corridor), and then fell into single file, with the 3-year-old in the rear.

"[They] walked very close to the side wall of the cave, a safer approach also used by other animals (e.g., dogs and bears) when moving in a poorly lit and unknown environment," Romano told Live Science in an email.

Shortly thereafter, the cave roof dropped to below 31 inches (80 centimeters), forcing the adventurers to crawl, "placing their hands and knees on the clay substrate," Romano said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The explorers then passed a bottleneck of stalagmites; traversed a small pond, leaving deep tracks on the waterlogged ground; climbed a small slope beyond the "Cimitero degli Orsi" (cemetery of the bears); and finally arrived at the terminal room "Sala dei Misteri" (room of mysteries), where they stopped.

Once in that room, "the adolescent and children started collecting clay from the floor and smeared it on a stalagmite at different levels according to height," Romano said. The group's torches left several charcoal traces on the walls. Then they left the cave.

The motley crew shows that "very young children were active members of the upper Palaeolithic populations, even in apparently dangerous and social activities," Romano said.

The new study is "a beautifully presented piece of work," said Matthew Bennett, a professor of environmental and geographical sciences at Bournemouth University in the United Kingdom, who was not involved in the research. "It's an example of the sophistication with which we can now record prints, whether they be humans or animals." [Photos: Dinosaur Tracks Reveal Australia's 'Jurassic Park']

However, given that researchers already knew that ancient humans lived in the area and used the cave, the finding doesn't add much to the scientific understanding of late Stone Age people, Bennett said. "It's a group of individuals exploring a cave, which is cool, but we knew that anyway," he told Live Science.

Bennett added that it's not uncommon to find the footprints of children intermingled with those of adults from this time. In part, that's because children likely outnumbered adults during the upper Paleolithic and because children take more steps than adults, as their legs are shorter. Moreover, "[children] do silly things — they dance around, they run around, they don't walk economically in one direction," Bennett said. "It makes statistical sense that we should be finding lots of children's footprints."

The study was published online today (May 14) in the journal eLife.

- Photos: Human Footprints Help Date Ancient Tibetan Site

- Top 10 Missing Links

- Top 10 Things That Make Humans Special

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.