Did the Maya Really Sacrifice Their Ballgame Players?

Imagine a crowd roaring as royalty take to the ball court, rubber ball in hand in a sport so spectacular, it symbolized good versus evil. The ballgame played by the Maya, Aztec and neighboring cultures is famous for its ubiquity in Mesoamerica before interloping Europeans shut it down. But many mysteries and misconceptions continue to dog people's understanding of the game.

For instance, did the game's winners or losers get sacrificed at the end of the game? And were the hoops on the ball courts treated like modern-day basketball nets?

The answer to both questions is no; the players were most likely not sacrificed, and the ball wasn't meant to go through the hoop, although it likely happened from time to time, said Christophe Helmke, an associate professor at the Institute of Cross-Cultural and Regional Studies at the University of Copenhagen. [What's the Toughest Sport?]

"It would have been really horrible if your best players were sacrificed all the time," said Helmke, who explained the inner workings of the game to Live Science.

What is the ballgame?

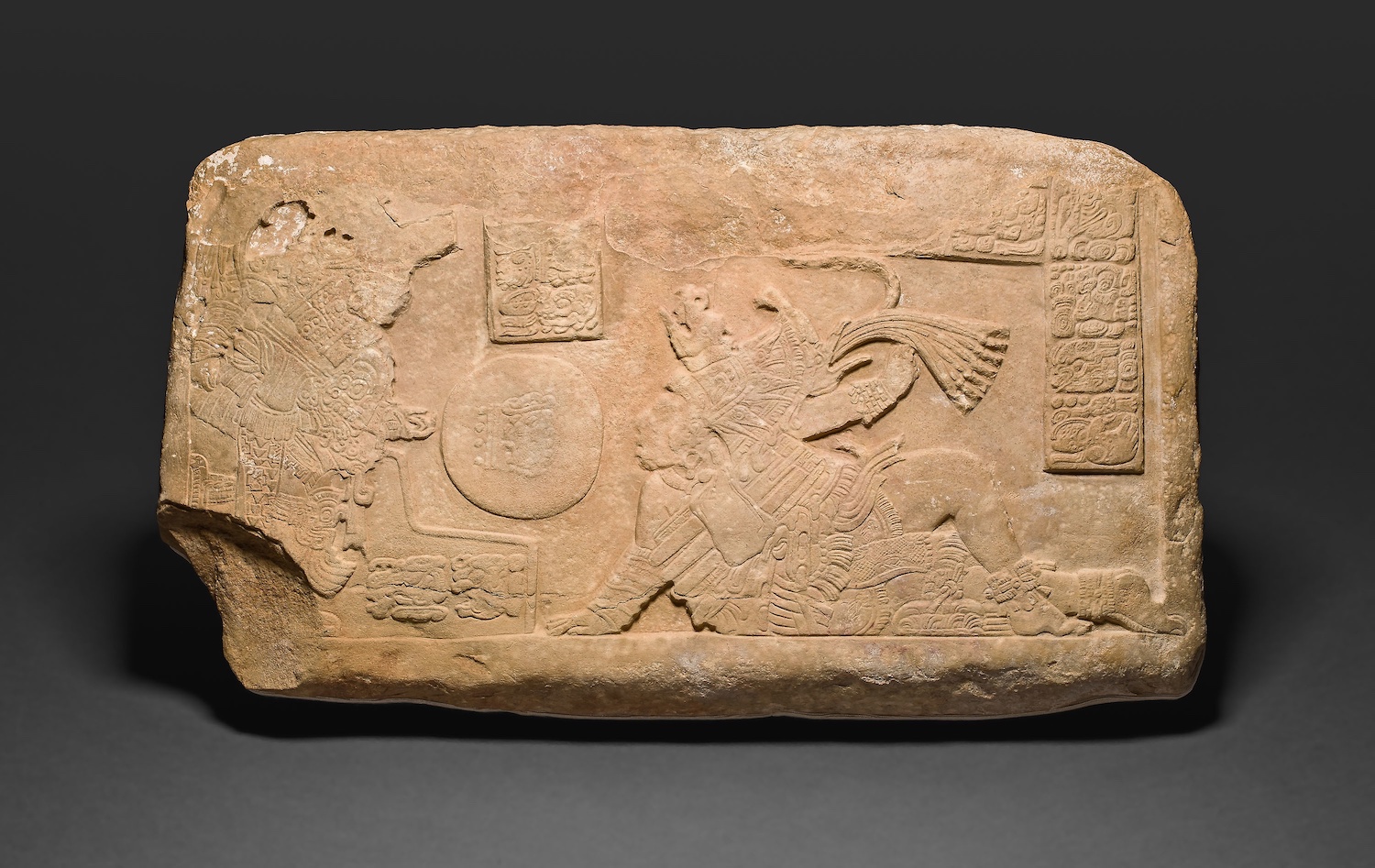

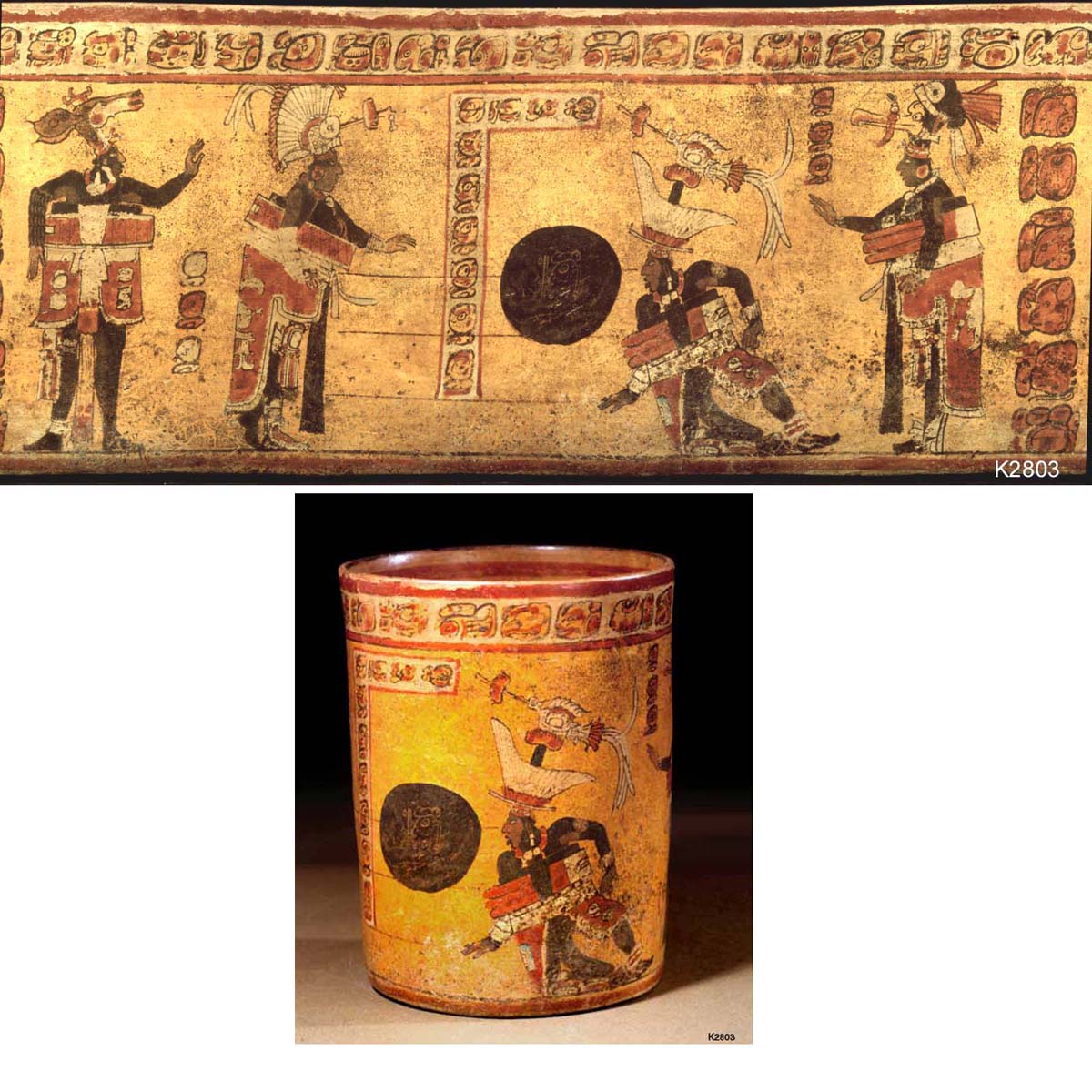

Archaeologists have pieced together information about the ballgame from different sources: excavations of historic ballcourts, documents from the colonial period (written either by Europeans or indigenous peoples who learned to write in English or Spanish) and from iconography — that is, indigenous glyphs depicting the game and its players.

Even today, some Mesoamerican cultures play the ballgame, although it's unclear how similar these games are to the ancient predecessor, Helmke said.

These various sources show that the ballgame was widespread and extremely important in the Pre-Columbian Americas, where it was played as far north as the American Southwest, in Arizona and New Mexico. It was also played throughout Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean, and even in northern South America, in Colombia.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Just like dialects, the rules likely varied in different places, Helmke said. But the ballgames had this in common: The sport was played on a capital I-shaped field known as a playing alley. Usually, the playing alley was adobe or smooth polished plaster, made from limestone. In other words, it would hurt if you fell on it, he said.

The top and bottom of the "I" marked the end zones where players could score. On either side of the long alley were sloped terraces, which would help keep the ball in play if it landed outside the court. "You can play the ball game without those [sloping] structures, but it's much more difficult because it just goes out of field," Helmke said.

"We've tried doing re-creations of the game," he added. "We found that the slope dictates how much the ball bounces. The more steeply angled the slope, the faster the pace of the game, the quicker the ball bounces back. The more obtuse the angle [was], the more easygoing it is."

The roughly 1,500 known ball courts vary in size. One at Chichen Itza in Mexico's Yucatan Peninsula is 316 feet long and 98 feet wide (96.5 meters by 30 m), "but it's more of a showpiece," Helmke said. "You can't actually play it in" because the distance is too great to return the ball without it bouncing on the ground. Most standard-size ball courts are about 65 feet (20 m) long, or about five times shorter than a football field, he said. [Photos: Carvings Depict Maya Ballplayers in Action]

The Rules

The Dominican friar Diego Durán never saw the ballgame in person, but he interviewed indigenous elders about it. Based on Durán's writings about the game from the early 1570s, the Aztecs would have tried to keep the ball in constant motion. Two teams would compete against each other, hitting the ball with their bodies, but not their hands or feet. Maya artwork shows ballplayers waiting to smack the ball with their hips, according to The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. In other regions, players used wooden paddles to strike the ball.

Teams could earn points if they drove the ball into the end zone or if the opposing team made a mistake or touched a teammate, Helmke said.

Sometimes royalty would play, in some cases inviting leaders of neighboring polities to compete in a show of allegiance, Helmke said. But regardless of whether royalty or regular athletes were on the playing alley, the games were heavily attended, with some people losing large sums, even their clothes, because they made big bets, Durán wrote.

In fact, the game served many purposes. For the Aztecs, it was seen as a sandlot sport for youth; a public game attended by spectators; a gladiatorial ritual, in which prisoners might be killed; a reenactment of cosmic conflict between the planets; and as a game the gods might play, according to a 1987 study in the journal Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics.

As for the hoops, Durán wrote that sometimes the ball would go through a hoop, located at the alley's midpoint. "If that happened, the whole game would stop and the person who put the ball through the hoop would be hailed a victor," Helmke said. "But he [Durán] didn't say that was the point of the game. He says that might happen once in a while and that it was truly exceptional."

Moreover, the vast majority of ball courts in the Maya area do not have hoops, Helmke added.

The earliest known ball court was found in Paso de la Amada, Guatemala, and dates to about 1400 B.C. However, rubber balls from the Gulf Coast of Mexico dating to 1600 B.C. may be the oldest artifacts of the game, the Met reported.

When they landed in the New World, the Spanish had never seen a ballgame, let alone a rubber ball. The Europeans were so intrigued, they sent a team of indigenous players to Spain to show the game to Charles V, according to the Met. But as the Spanish began conquering Mesoamerica in 1519, they stamped out the game, forbidding anyone from playing it because of its associations with human sacrifice and "idolatrous" religious practices, according to the study in Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics.

Human sacrifice

Given how popular and well-attended the ballgames were, sometimes a captive might be executed at the game, Helmke said. "But [these sacrifices] weren't an integral part of the game. That person would have been expedited [executed] anyway." [25 Cultures That Practiced Human Sacrifice]

Despite this, it's hard to shed the modern perception that ballgame players were often sacrificed, Helmke said. Part of this misconception stems from the Popol Vuh — an epic that tells the creation myth of one of the Maya peoples. The Popol Vuh began as an oral tradition that was later written down by an indigenous leader, and then recopied by Dominican friar Francisco Ximénez in the early 1700s.

In the Popol Vuh (which means "Book of the People" — you can read the full text here), underworld deities battle and use trickery to triumph in a ballgame against humans, whom the deities then decapitate. Then, the twin sons of one of the murdered heroes face off against the underworld deities, and this time the humans win and dismember the underworld lords.

In addition to the association between the game and the gory Popol Vuh, this "human sacrifice" myth stems from artwork on some ball courts featuring skulls and bones. "But the question is, 'Are those references to the underworld and that mythical event? Are they supposed to be taken literally?' I think it's an open question," Helmke said.

- How Does Caffeine Help Athletes?

- Does Grunting Help Tennis Players?

- Why Do Athletes Train at High Altitudes?

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.