Canada Makes a Claim to the North Pole

The mystique of the North Pole, at the very top of the world, has long driven explorers to risk their lives in the Arctic — while those of us not so adventurously inclined look on in awe. Now, three northern nations are vying to stake their claim to part of the Arctic seafloor, a region chock-full of fossil fuels that lies under thousands of miles of water and ice.

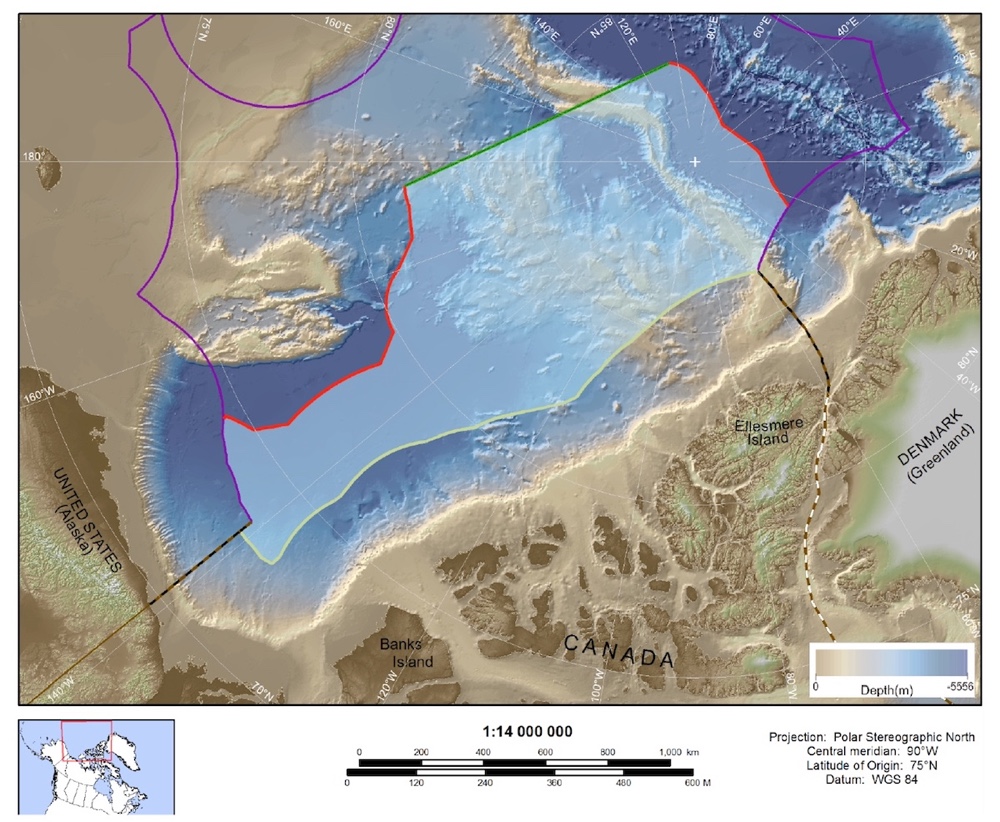

Late last month, Canada threw its metaphorical hat into the ring, joining Russia and Denmark in arguing that science is on their side in laying claim to almost half a million square miles of underwater Arctic territory, based on the extent of its continental shelf — including the geographic North Pole.

At the center of the debate is the 1,100-mile-long (1,800 kilometers) Lomonosov Ridge, a region at a depth of around 5,600 feet (1,700 m) that runs near the pole and bisects the Arctic Ocean. The ridge, which is about the size of California, is considered a promising source for oil and gas, according to The New York Times. So, who owns that area of seafloor?

To establish their case, Canadian officials have submitted a 2,100-page report to a scientific committee of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), detailing the size and shape of the continental shelf along Canada's Arctic coastline. The extent of the continental shelf was determined by scientists on board several ship-based expeditions to the polar ocean, between 2006 and 2016. [On Ice: Stunning Images of Canadian Arctic]

After the Canadian submission is evaluated by the U.N. committee, probably in several years' time, the three nations will start negotiations on the final delimitations of their Arctic territory, including their competing claims to the pole. Regardless of the outcome, the seawater and ice above the North Pole will remain an area of open navigation for ships from any country, said Michael Byers, the author of "International Law and the Arctic" (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

90 degrees north

Byers explained that UNCLOS lets nations claim an "exclusive economic zone" at sea within 200 miles (370 km) of their coastlines.

But, if the claim is supported by scientific evidence, the convention also lets nations claim territory out to a much greater distance — something that's based on the extent of their continental shelf. [The 7 Harshest Environments on Earth]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Russia first made a scientific submission under UNCLOS in 2001, and Denmark made its submission in 2014. Byers said each nation is scientifically correct when it asserts that its continental shelf extends beyond the North Pole, which would mean they can each lay claim to the pole itself.

"All three countries' scientists take the view that it is the same continental shelf all the way around the ocean, because North America used to be part of the same continent as Eurasia," Byers told Live Science.

North America, including Greenland, separated from the Eurasian continent around 60 million years ago, forming today's Arctic Ocean.

Ice cold

Since 2006, scientists working for the Canadian government have staged 17 shipboard expeditions into the Arctic to gather data about the outer limits of the continental shelf. The most recent expeditions took place in 2014, 2015 and 2016.

Oceanographer Mary-Lynn Dickson, the director of the UNCLOS program for the government department Natural Resources Canada and the chief scientist on board the 2016 expedition, said the scientists involved had made a strong argument for defining the limits of Canada's continental shelf.

The different Canadian expeditions studied bathymetric data from the oceans and geophysical data from the seafloor over an area of more than 463,000 square miles (1.2 million square kilometers) of the Arctic, to determine the extent of Canada's underwater continental shelf, The Barents Observer reported.

The studies included inspections of the seafloor by autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) — essential in areas where heavy ice made working from the ship impossible — and even rock samples from thousands of feet below that she told Live Science were "rarer than moon rocks."

Frozen fuel

The Canadian submission on the extent of its territory in the Arctic comes amid a flurry of interest in the region among powerful world nations, including Russia, the United States and China.

For decades, the North Pole has been covered by thick sea ice for most of the year. But international interest has been spurred by the prospects of climate change in the Arctic making the region open to ships for longer periods each year.

Undersea natural resources may also play a part. An estimated 90 billion barrels of oil and trillions of cubic feet of natural gas are thought to lie under the polar oceans, according to the U.S. Geological Survey, although the central North Pole region is not thought to be especially rich in fossil fuels.

Canada, Denmark and Russia are likely to be more interested in undersea fuel reserves that lay closer to their coastlines than in the distant and frozen North Pole, said political scientist Andreas Østhagen of the Fridtjof Nansen Institute in Norway.

"They are struggling to utilize or exploit resources that are much closer to shore," Østhagen told Live Science. "So, from a resource perspective, I don't really see how this matters at all."

Ownership of the North Pole itself is an important symbol of national prestige, however. "This plays into the narrative of Arctic sovereignty, protecting your Arctic territory, and upholding your Arctic presence," he said. "The North Pole is a symbolic prize in all this."

Byers said that Canada, Denmark, and Russia have all agreed to abide by the results of the UNCLOS negotiations.

"This is a really exciting story about science being used to resolve issues that otherwise might cause tensions between different states," he said.

- In Photos: A Conveyor Belt for Arctic Sea Ice

- In Photos: The Vanishing Ice of Baffin Island

- In Photos: Norwegian Explorer's Ship Raised from the Arctic

Follow Tom Metcalfe on Twitter @globalbabel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.