AI Listened to People's Voices. Then It Generated Their Faces.

Have you ever constructed a mental image of a person you've never seen, based solely on their voice? Artificial intelligence (AI) can now do that, generating a digital image of a person's face using only a brief audio clip for reference.

Named Speech2Face, the neural network — a computer that "thinks" in a manner similar to the human brain — was trained by scientists on millions of educational videos from the internet that showed over 100,000 different people talking.

From this dataset, Speech2Face learned associations between vocal cues and certain physical features in a human face, researchers wrote in a new study. The AI then used an audio clip to model a photorealistic face matching the voice. [5 Intriguing Uses for Artificial Intelligence (That Aren't Killer Robots)]

The findings were published online May 23 in the preprint jounral arXiv and have not been peer-reviewed.

Thankfully, AI doesn't (yet) know exactly what a specific individual looks like based on their voice alone. The neural network recognized certain markers in speech that pointed to gender, age and ethnicity, features that are shared by many people, the study authors reported.

"As such, the model will only produce average-looking faces," the scientists wrote. "It will not produce images of specific individuals."

AI has already shown that it can produce uncannily accurate human faces, though its interpretations of cats are frankly a little terrifying.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

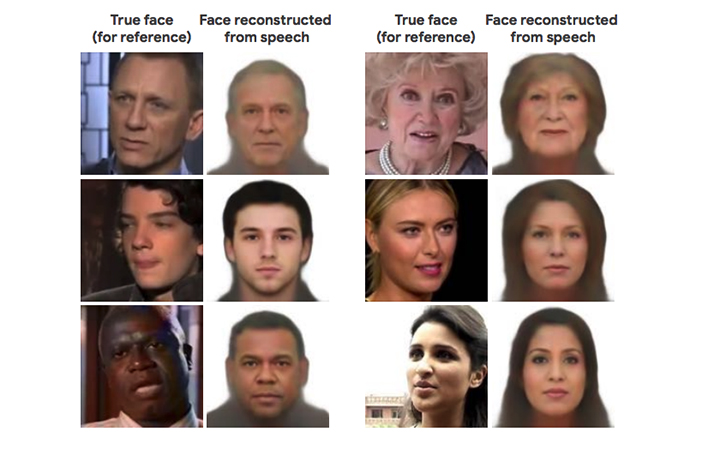

The faces generated by Speech2Face — all facing front and with neutral expressions — didn't precisely match the people behind the voices. But the images did usually capture the correct age ranges, ethnicities and genders of the individuals, according to the study.

However, the algorithm's interpretations were far from perfect. Speech2Face demonstrated "mixed performance" when confronted with language variations. For example, when the AI listened to an audio clip of an Asian man speaking Chinese, the program produced an image of an Asian face. However, when the same man spoke in English in a different audio clip, the AI generated the face of a white man, the scientists reported.

The algorithm also showed gender bias, associating low-pitched voices with male faces and high-pitched voices with female faces. And because the training dataset represents only educational videos from YouTube, it "does not represent equally the entire world population," the researchers wrote.

Another concern about this video dataset arose when a person who had appeared in a YouTube video was surprised to learn that his likeness had been incorporated into the study, Slate reported. Nick Sullivan, head of cryptography with the internet security company Cloudflare in San Francisco, unexpectedly spotted his face as one of the examples used to train Speech2Face (and which the algorithm had reproduced rather approximately).

Sullivan hadn't consented to appear in the study, but the YouTube videos in this dataset are widely considered to be available for researchers to use without acquiring additional permissions, according to Slate.

- Can Machines Be Creative? Meet 9 AI 'Artists'

- Flying Saucers to Mind Control: 22 Declassified Military & CIA Secrets

- Super-Intelligent Machines: 7 Robotic Futures

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.