Mysterious Etchings in Peruvian Desert Prove to Be Foreign Birds. What Did They Mean to the Pre-Incans?

The sprawling Nazca Lines have long been cloaked in mystery. The enormous geoglyphs number in the thousands and portray everything from animals and plants to seemingly mythical beasts and geometric patterns. Now, researchers have found some of Peru's massive creations depict non-native birds.

Among the 16 massive bird carvings in the Nazca desert of southern Peru are a hermit (a forest species) and a pelican (a coastal denizen), according to new research published yesterday (June 19) in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.

No one knows why the Nazca Lines were made, and it's too early to say why the pre-Inca people who carved them would have been interested in non-native birds, said study co-author Masaki Eda, a zooarchaeologist at the Hokkaido University Museum in Japan. [In Images: The Mysterious Nazca Lines]

Nazca mystery

The Nazca Lines are enormous geoglyphs, created with piled stones or carved into the dry desert ground. Most are geometrical shapes or drawings of animals made with one continuous line; they're best viewed from the air or from surrounding hillsides.

The Nazca people began crafting these lines — both by carving into the desert and using piles of stones — around 200 B.C. Archaeologists suspect they had a religious purpose, perhaps the creations served as labyrinths that pilgrims or priests may have walked. Eda began looking at the birds of the Nazca Lines at the behest of study co-author Masato Sakai, an expert in the lines at Yamagata University in Japan. Eda was working to identify bird bones at a nearby archaeological site in the Nazca desert when he became interested in studying the lines themselves from a biological perspective.

"I believe that the motifs of the animal geoglyphs are closely related to the purpose [of] why they were etched," Eda told Live Science.

Ornithological archaeology

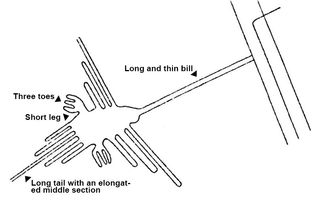

Using an ornithologist's approach, Eda and his team studied the anatomical characteristics of each of the 16 bird etchings, categorizing features such as the shape of the beak and tail and the relative length of the tail and feet. They were able to identify three birds with confidence. One famous glyph, previously identified generally as a hummingbird, actually appears to be a hermit, a subgroup of hummingbirds found in the tropics and subtropics, the researchers reported. Hermits live in the forests of northern and eastern Peru, but not in the southern desert.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Another surprise, Eda said, was the discovery that another of the glyphs represents a pelican, which would have been found only on the coast. The third identifiable glyph shows a guano bird, which represents an important group of species in Peru to this day. On islands off the country's coast, the Guanay cormorant, the Peruvian booby and the Peruvian pelican leave huge amounts of bird poop, or guano, which became a hugely valuable commodity for British speculators in the mid-1880s because it makes an excellent fertilizer. Bird guano is still harvested from the islands today.

The next step, Eda said, is to study the representations of birds at Nazca temple sites and on Nazca ceramics. Comparisons between all three examples of bird drawings could help explain why the Nazca chose to feature the birds they did, he said. That work is still ongoing, Eda said, but the team has already found some differences in the types of birds presented in the three different contexts.

- Photos: Circular Geoglyphs Discovered in Peru's Sihuas Valley

- In Photos: Google Earth Reveals Sprawling Geoglyphs in Kazakhstan

- In Photos: Mysterious Amazonian Geoglyphs

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.