What Is Trypophobia?

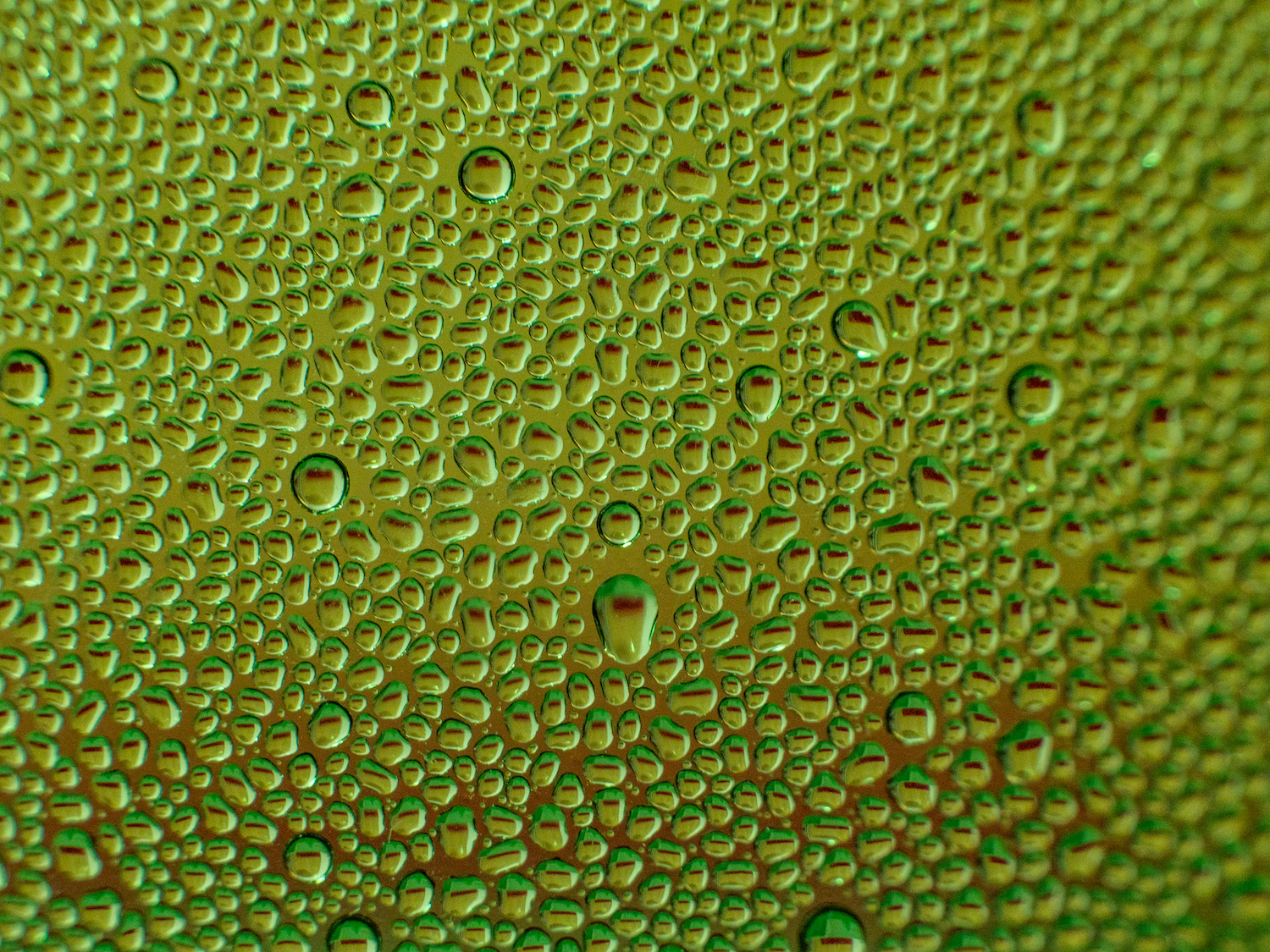

Does the sight of natural sponges, honeycomb cells or bubbly pancake batter make your skin crawl? You may be among thousands of people with trypophobia — an extreme aversion to clustered patterns of irregular holes or bumps. Viral images of lotus seed pods, pregnant Surinam toads and woodpeckers storing fruit in trees have triggered reactions from trypophobes online, and raised awareness of the condition. Though anecdotally widespread, the phobia is not listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), the diagnostic guide for mental disorders recognized by professional psychologists.

Causes and symptoms of trypophobia

Upon seeing a dimpled piece of coral, bubble-filled bathtub or even aerated chocolate, a person with trypophobia may become overcome with disgust or feel physically ill. They may feel their heart race, head pound or skin crawl. Sometimes, even a narrative description of a triggering visual can incite these symptoms, no picture needed. [Clowns or Holes: What Is Your State Most Afraid Of?]

Most trypophobic people show disgust as their main symptom, which is uncommon in recognized phobias, where fear is more prevalent, according to a 2018 review in Frontiers of Psychiatry. Women appear more likely to develop trypophobia, and its most common comorbid diagnoses are major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder.

A phobia is a type of anxiety disorder that can trigger symptoms of nausea, dizziness, heart palpitations, trembling and feelings of panic, according to the National Health Service. Phobias develop when people have an exaggerated sense of fear about a situation, place, feeling or object; this overwhelming reaction may stem from their own traumatic experiences or from responses they've picked up from observing others. The chances of developing a phobia depends on a person's genetic history.

"It is important to understand the underlying reasons for the individual's aversion to objects or images with small holes," psychologist Anthony Puliafico, assistant professor of clinical psychology at Columbia University, New York, told Live Science in an email. "If an individual is just 'grossed out' by pictures of small holes or patterns, but their aversion does not impair their functioning, this would not be a phobia."

In other words, a phobia must "significantly interfere with the person's normal routine," as stated in the DSM-5. Scientists remain dubious as to whether trypophobia meets this criterion, though more research may resolve that question.

Is trypophobia real?

The term "trypophobia" is thought to have originated on an online forum entitled "A Phobia of Holes." A user named Louise from Ireland consulted the Oxford Word and Language Service for help crafting the word, which translates to "fear of boring holes" in Greek.

The term came into popular usage in 2009, when a University of Albany student named Masai Andrews founded the website Trypophobia.com and a trypophobe support group on Facebook, according to Popular Science. As of today, the public group has over 13,600 members. A newer sister group, called "Trypophobia Triggers," acts as an archive of pockmarked, pitted images that send members' stomachs turning.

After an extended struggle, the trypophobe community secured a Wikipedia page describing the condition. Wikipedia editors had deleted an attempted page in 2009, stating that trypophobia was "likely hoax and borderline patent nonsense," the Washington Post reported. The fear has now secured pop culture fame and was even featured in the seventh season of the TV series "American Horror Story," as highlighted by BuzzFeed.

What the science says

Trypophobia first entered scientific literature in 2013, when researchers proposed that the condition stems from an innate aversion to dangerous animals. The scientists lit upon the idea when one of their study participants mentioned their fear of the blue-ringed octopus, a highly poisonous animal with bruise-colored spots. The researchers realized that many dangerous animals, such as the box jellyfish, inland taipan snake and poison dart frog, share similar visual features to trypophobia triggers; namely, their patterns are typically high-contrast and clustered, but not so close that they overlap.

Some scientists theorize that trypophobia is not a overgeneralized fear of animals, but of human disease. Many infectious diseases and parasites leave the skin riddled with spots and sores — think of smallpox, scarlet fever or botfly bites. A 2017 study suggested that this overlap may explain the nausea and "skin crawling" sensations conjured by the condition.

Other evidence suggests that trypophobia triggers simply provoke visual discomfort, and that some people are particularly sensitive to their effects, such as eyestrain and perceptual distortions. In addition, a 2016 study found that trypophobes tend to be highly empathetic and sensitive to disgusting stimuli. Ultimately, scientists still haven't pinned down the underlying cause of the condition.

How to cure trypophobia

Though it's not listed in the DSM5, trypophobia can cause disturbance in people's lives.

"As for any fear or aversion, if your symptoms are persistent and distressing or impairing, I would recommend consulting with a mental-health professional with expertise in exposure treatment," Puliafico said. In exposure treatment, a therapist guides an individual in gradually facing objects or situations that provoke fear or disgust. "There is growing evidence that specific phobias can be treated intensively, and in certain cases after just a single exposure session."

Additional Resources

- See if your skin crawls at the sight of Suriname sea toads giving birth, from National Geographic.

- Learn more about anxiety disorders and phobias in this video from Crash Course.

- Read more about what defines a phobia according to Harvard Medical School.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.