Miners Looking for Gemstones Find Ancient Sea Monster Instead

Miners digging for gemstones found something entirely different last month; rather than uncovering the shiny and iridescent gemstone known as ammolite, they discovered the fossilized remains of an ancient sea monster.

Paleontologists could barely contain their glee. The ancient sea monster was the nearly complete skeleton of a marine reptile known as a mosasaur, likely of the genus Tylosaurus, that lived during the dinosaur age about 70 million years ago.

During that time, Alberta, Canada (where the mosasaur was found) lay underwater, covered by the Western Interior Seaway, which stretched from the Gulf of Mexico to the Arctic Sea. [T-Rex of the Seas: A Mosasaur Gallery]

"We've got everything from the head almost to the tip of the tail," said Donald Henderson, curator of dinosaurs at the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology in Drumheller, Alberta. "We don't have much in the way of flippers. They were lost to decay, or maybe they were bitten off."

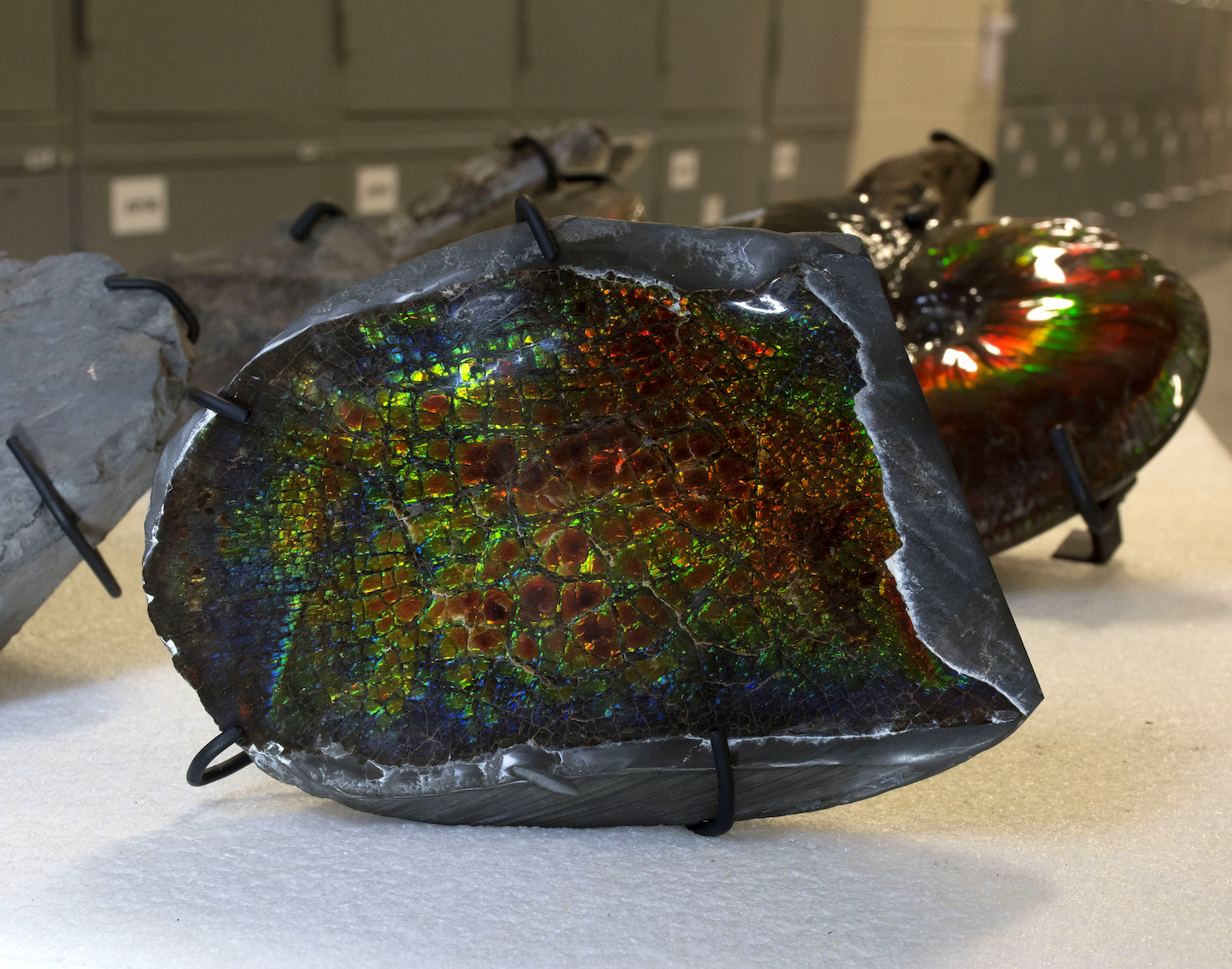

Enchanted Designs Limited, the company that found the mosasaur, in June, was looking for pieces of rainbow-colored ammolite that could be made into jewelry. This opal-like gemstone is made from the fossilized shells of ammonites, an extinct marine mollusk with a circular shell whose distant living relatives include the nautilus.

Miners digging at the Bearpaw Formation (named for the Bears Paw Mountains in Montana, just south of Alberta) usually find from one to two fossilized marine reptiles a year, so this discovery wasn't completely unexpected. But it's not every day that such a nearly complete skeleton is unearthed.

Interestingly, the mosasaur's remains were a bit offset, Henderson said. "It was probably quite rotten when it [the body] went to the seabed," he told Live Science. "It looks like it maybe ruptured or broke when it hit the seabed, but otherwise it's pretty good."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The fossils were embedded in fairly soft black-shale mudstone, so the preparation of the skeleton is nearly complete. In all, the beast is between 20 and 23 feet (6 and 7 meters) long, Henderson said.

"These things tend to be big," he said. "I think they had to be big to survive in that environment."

Mosasaurs were apex predators. (However, take note that they were reptiles, not dinosaurs.) Fossil findings of a mosasaur stomach and bite marks on other fossils show that these beasts ate turtles, fish, ammonites and even other mosasaurs. One of their secret weapons came in the teeth on the roofs of their mouths that curved backward.

"Once they grabbed you with their main teeth and started to work you back, those teeth would keep the food from struggling out," Henderson said. "So, the only way you could slide was down the throat."

It's not yet clear when or if the mosasaur will go on display. But the public can see other mosasaur specimens in the Royal Tyrrell Museum's Dinosaur Hall or its Grounds for Discovery exhibit.

- Image Gallery: Ancient Monsters of the Sea | Predator X

- Image Gallery: 25 Amazing Ancient Beasts

- Photos: Uncovering One of the Largest Plesiosaurs on Record

Editor's note: This story was corrected to say that Enchanted Designs Limited, not Korite miners, found the specimen.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.