Osteoporosis: Risks, Symptoms and Treatment

Osteoporosis is a common disease that makes bones weak, thin, brittle and more likely to break. The condition typically occurs in women after menopause and can increase the risk of fractures, especially in the hip, spine and wrist, according to the National Institutes of Health.

The condition is often called a "silent disease" because bone loss can happen slowly and without any warning signs. People may not be aware they have osteoporosis until they break a bone, lose height or develop hunched posture.

About 10 million Americans have osteoporosis, and another 44 million have low bone mass, or osteopenia, placing them at increased risk for osteoporosis, according to the National Osteoporosis Foundation.

There are a number of factors that may lead to osteoporosis, said Dr. Harold Rosen, an endocrinologist and director of the Osteoporosis Prevention and Treatment Center at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. One such factor is the accelerated bone loss that occurs after menopause, he said.

Men also lose bone as they age, normally once they're in their 60s and 70s, Rosen said. Some men think osteoporosis affects only women, but it strikes men too, he explained.

Low calcium intake and low vitamin D levels in the body can also lead to bone loss, Rosen told Live Science. The body needs a good supply of calcium and other minerals to form bone, and vitamin D helps absorb calcium from food and incorporate the nutrient into bone. In addition, unhealthy habits, such as smoking and excessive drinking, can speed up bone loss, he said.

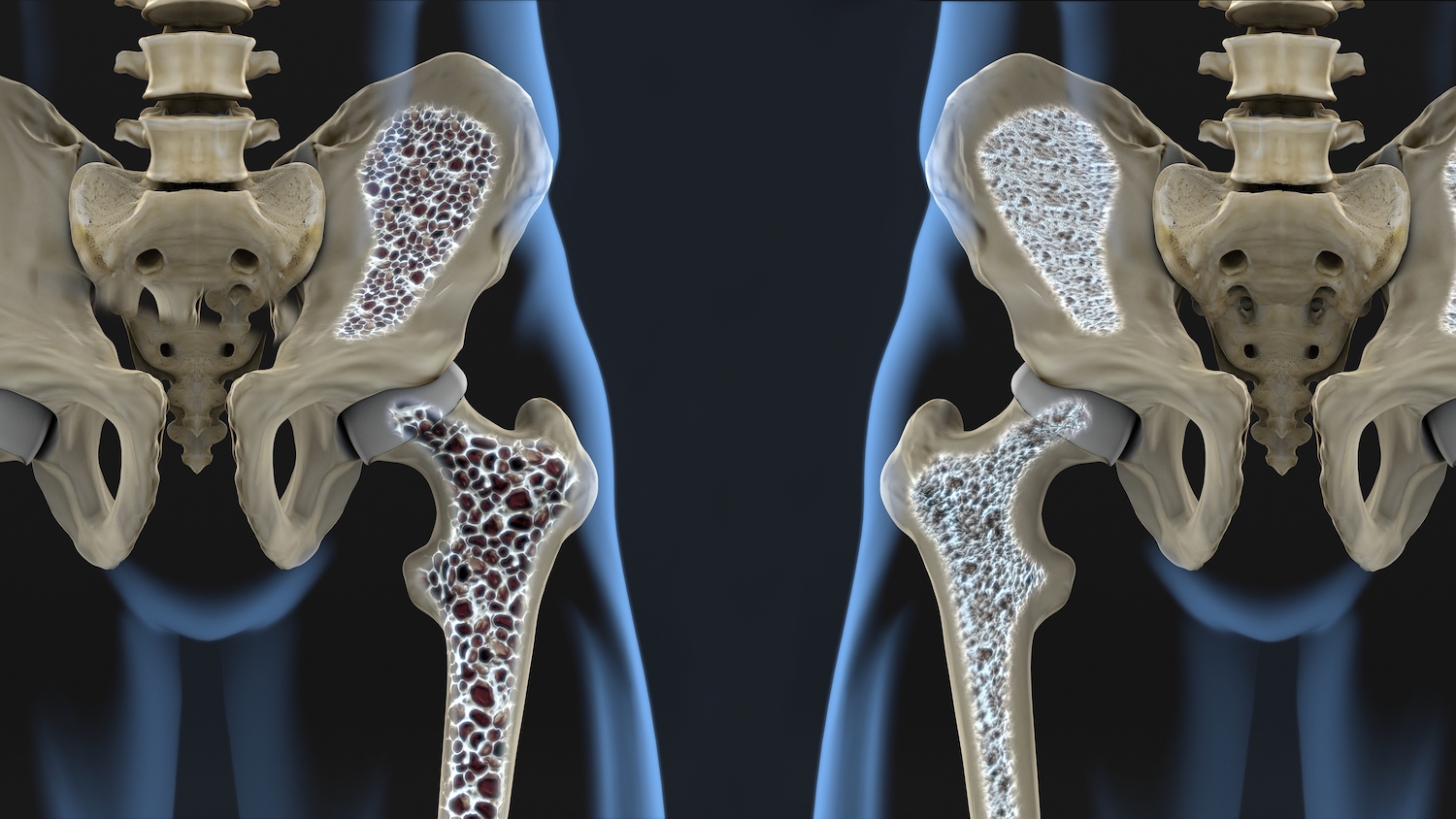

How bone changes over time

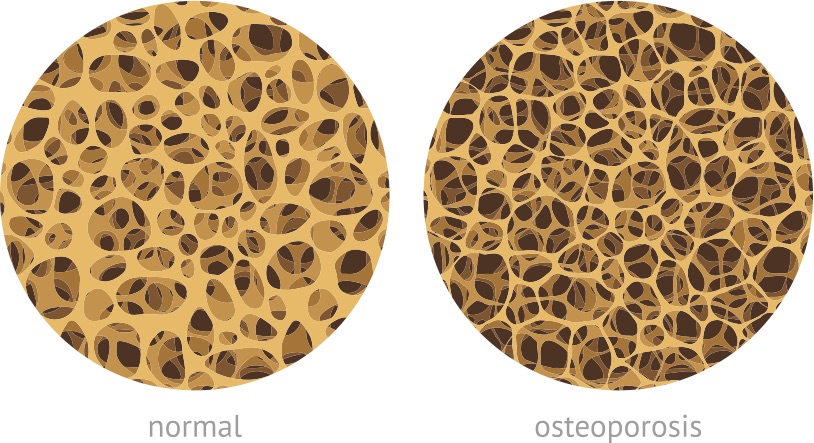

The body is continually breaking down small areas of old bone tissue, a process called bone resorption, and replacing that old tissue with new bone tissue. During childhood and adolescence, new bone is deposited faster than old bone is removed. This makes bones larger, heavier and denser.

Peak bone mass, or when bones reach their maximum density and strength, typically occurs around age 30 for both sexes. Around age 35, bone breakdown occurs faster than the replacement by new bone, causing a gradual loss of bone mass, according to the National Institute on Aging.

Women undergo more-rapid bone loss in the first few years after menopause (around age 51) than in their 30s and 40s because the ovaries produce much less estrogen, a hormone that protects against bone loss, according to The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Men in their 50s and 60s also start to lose bone mass, but at a slower rate than women do. It's not until ages 65 to 70 that men and women begin losing bone mass at about the same rate.

For that reason, osteoporosis is more common in women. The condition affects about 25% of women and 5% of men ages 65 and over, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Can osteoporosis be prevented?

The more bone a person builds early in life, the better that individual can resist bone loss later on. Prevention should start when people are younger, during their peak bone-building years, with the following steps, according to the National Osteoporosis Foundation:

- Consuming adequate amounts of foods rich in calcium and vitamin D throughout life.

- Getting regular weight-bearing exercise.

- Maintaining a healthy lifestyle, such as avoiding smoking and limiting alcohol consumption, reduces bone loss.

Osteoporosis risk factors

The following factors can increase a person's risk of developing osteoporosis, according to the Cleveland Clinic.

- Age: Bones typically become thinner and weaker with age.

- Sex: Women are more likely to develop osteoporosis than men, because women have less bone tissue and lose bone faster after menopause.

- Body size: Petite and thin people are at greater risk of this condition because they have less bone to lose than people with larger frames and more body weight.

- Ethnicity: White and Asian women have the highest risk of osteoporosis, while African American and Hispanic women have a lower risk.

- Family history: People whose parents had a hip fracture may be more likely to develop the disease.

- Nutrition: Eating a diet that's low in calcium and vitamin D increases osteoporosis risk.

- Being a couch potato: Not getting enough physical activity or too much bed rest following an injury, illness or surgery weakens bones over time.

- Medications: Using certain drugs on a long-term basis can lead to bone loss. These medicines include corticosteroids, such as prednisone; heparin, a blood thinner; selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), a class of antidepressants; and aromatase inhibitors, used to treat breast cancer.

- Unhealthy habits: Smoking and consuming too much alcohol can both increase bone loss.

- Medical problems: Numerous health conditions and diseases can also increase a person's risk for osteoporosis.

Osteoporosis symptoms and diagnosis

Osteoporosis may cause no symptoms in its early stages, and as a result, the disease can go unnoticed for decades.

Some visible signs of osteoporosis may be a loss of height and a curve in the upper back, which may cause stooped posture. A "dowager's hump" may occur when several vertebrae collapse from osteoporotic fractures in the spine.

Other symptoms may include back pain, from a fracture or a collapsed vertebra in the spine, or tooth loss, if osteoporosis has affected the jawbone.

Hip fracture is another serious consequence of osteoporosis. About 20% of older adults who fracture a hip die within one year from complications of the broken bone or the surgery needed to repair it, according to the National Osteoporosis Foundation.

Doctors may perform a bone mineral density (BMD) test to determine if a patient has osteoporosis, according to the Mayo Clinic. The test uses a special X-ray machine to measure the mineral content at three different bone sites, typically the hip, the spine and the top of the femur. The scan can reveal if a person has low bone mass at any of these three bone sites by comparing the patient's bone density to the normal bone density in a healthy 30-year-old person of the same sex.

BMD testing is recommended for women who are 65 or older and for women 50 to 64 who have certain risk factors for the disease. Men over the age of 70 or younger men with risk factors should also be screened for osteoporosis.

Osteoporosis treatment and medications

People with advanced osteopenia as well as those with osteoporosis need medication to reduce their risk of fractures.

Bisphosphonates are usually the first drugs used to treat osteoporosis, but while they help slow bone loss, they don't help build new bone. These drugs include alendronate (Fosamax), risedronate (Actonel) and ibandronate (Boniva). Studies have shown that alendronate can reduce the risk of spine and hip fractures by up to 50%, Rosen said.

Once a person has started treatment for osteoporosis, bone-density testing should be repeated every two to three years to monitor how the density is changing and whether treatment is working, Rosen said.

For severe osteoporosis, patients may need one of three medications given by injection that actually build new bone, Rosen said. These include teriparatide (Forteo), abaloparatide (Tymlos) and romosozumab (Evenity). But after a year on these bone-building drugs, a patient needs to take bisphosphonates; otherwise, all the bone-density gains will be lost, Rosen said.

In addition to medication, people with osteoporosis should aim to include 1,200 milligrams of calcium a day in their diet, from food or supplements (preferably calcium citrate), Rosen said. He also recommends taking 1,500 to 2,000 International Units (IU) of supplemental vitamin D each day.

Being physically active is also beneficial for people with osteoporosis. Rosen recommends regular workouts that include weight-bearing aerobic activity, as well as strength training, balance and posture exercises.

Additional resources:

- Review this list of calcium-rich foods from the University of California, San Francisco Medical Center.

- Download a helpful brochure from Osteoporosis Canada on managing osteoporosis through exercise.

- Learn more about osteoporosis in men from the National Institutes of Health.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Cari Nierenberg has been writing about health and wellness topics for online news outlets and print publications for more than two decades. Her work has been published by Live Science, The Washington Post, WebMD, Scientific American, among others. She has a Bachelor of Science degree in nutrition from Cornell University and a Master of Science degree in Nutrition and Communication from Boston University.