12,000 Years Ago, a Boy Had His Skull Squashed into a Cone Shape. It's the Oldest Evidence of Such Head-Shaping.

Ancient people in China practiced human head-shaping about 12,000 years ago — meaning they bound some children's maturing skulls, encouraging the heads to grow into elongated ovals — making them the oldest group on record to purposefully squash their skulls, a new study finds.

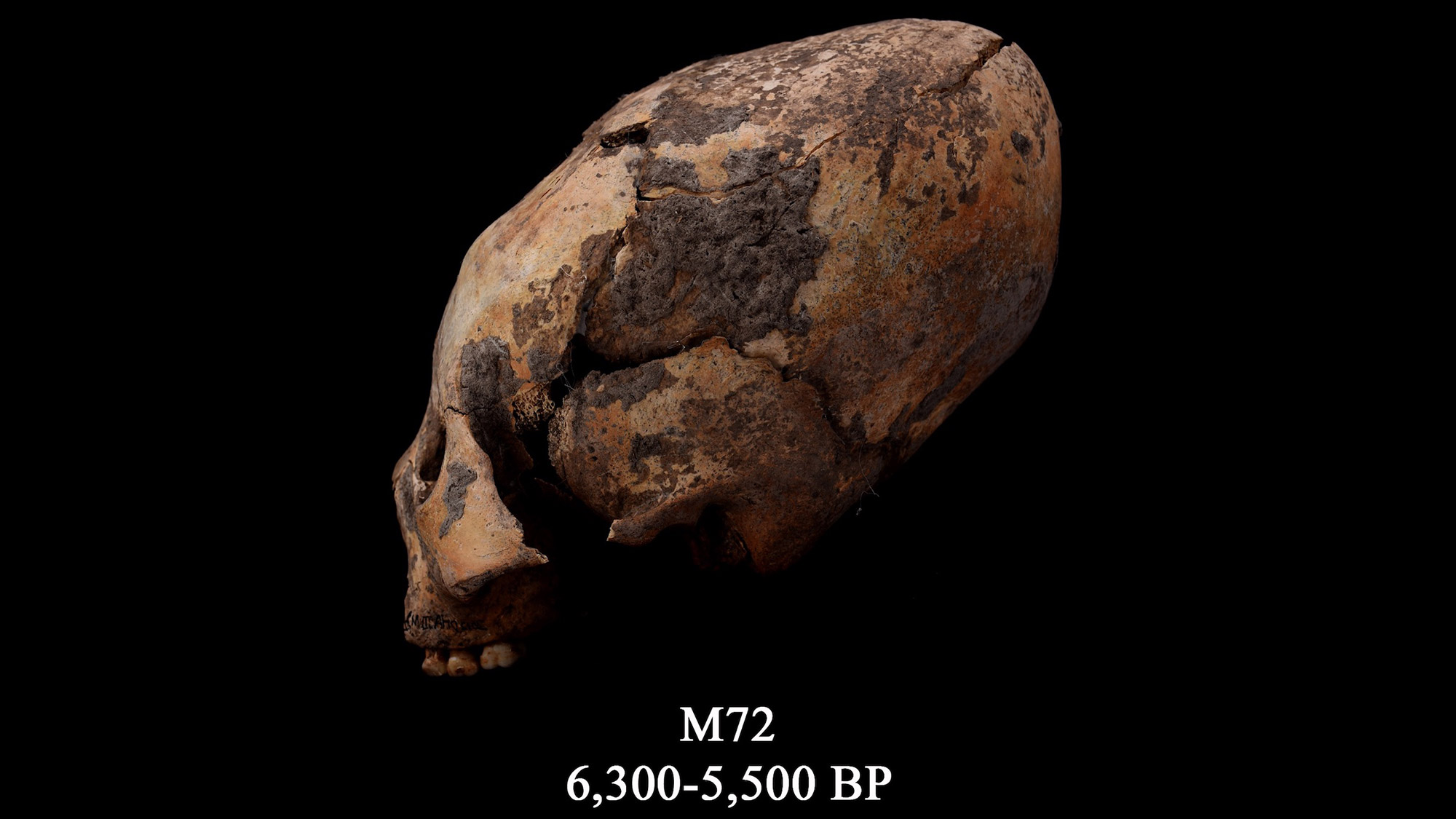

While excavating a Neolithic site (the last period of the Stone Age) at Houtaomuga, Jilin province, in northeast China, the archaeologists found 11 elongated skulls — belonging to both males and females and ranging from toddlers to adults — that showed signs of deliberate skull reshaping, also known as intentional cranial modification (ICM).

"This is the earliest discovery of signs of intentional head modification in Eurasia continent, perhaps in the world," said study co-researcher Qian Wang, an associate professor in the Department of Biomedical Sciences at the Texas A&M University College of Dentistry. "If this practice began in East Asia, it likely spread westward to the Middle East, Russia and Europe through the steppes as well as eastward across the Bering land bridge to the Americas." [In Images: An Ancient Long-headed Woman Reconstructed]

The Houtaomuga site is a treasure trove, holding burials and artifacts from 12,000 to 5,000 years ago. During an excavation there between 2011 and 2015, archaeologists found the remains of 25 individuals, 19 of which were preserved enough to be studied for ICM. After putting these skulls in a CT scanner, which produced 3D digital images of each specimen, the researchers confirmed that 11 had indisputable signs of skull shaping, such as flattening and elongation of the frontal bone, or forehead.

The oldest ICM skull belonged to an adult male, who lived between 12,027 and 11,747 years ago, according to radiocarbon dating.

Archaeologists have found reshaped human skulls all around the world, from every inhabited continent. But this particular finding, if confirmed, "will [be] the earliest evidence of the intentional head modification, which lasted for 7,000 years at the same site after its first emergence," Wang told Live Science.

The 11 ICM individuals died between ages 3 and 40, indicating that skull shaping began at a young age, when human skulls are still malleable, Wang said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

It's unclear why this particular culture practiced skull modification, but it's possible that fertility, social status and beauty could be factors, Wang said. The people with ICM buried at Houtaomuga were likely from a privileged class, as these individuals tended to have grave goods and funeral decorations.

"Apparently, these youth were treated with a decent funeral, which might suggest a high socioeconomic class," Wang said.

Even though the Houtaomuga man is the oldest known case of ICM in history, it's a mystery whether other known instances of ICM spread from this group, or whether they rose independently of one another, Wang said.

"It is still too early to claim intentional cranial modification first emerged in East Asia and spread elsewhere; it may have originated independently in different places," Wang said. More ancient DNA research and skull examinations throughout the world may shed light on this practice's spread, he said.

The study was published online June 25 in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology.

- 25 Grisly Archaeological Discoveries

- The 25 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth

- Back to the Stone Age: 17 Key Milestones in Paleolithic Life

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.