Modern Humans Failed in Early Attempt to Migrate Out of Africa, Old Skull Shows

A prehistoric, broken skull is revealing the secrets of ancient humans, divulging that early modern humans left Africa much earlier than previously thought, a new study finds.

The skull, found in Eurasia and dating back 210,000 years, is the oldest modern human bone that anthropologists have discovered outside Africa, the researchers said.

This skull, however, had an unusual neighbor: a 170,000-year-old, possibly Neanderthal skull that was found resting next to it, in a cave in southern Greece. Given that the Neanderthal skull is a solid 40,000 years younger than the modern human skull, it appears that this particular human's early dispersal out of Africa failed. There are no living descendants of this enigmatic human alive today, and this person's group was replaced by Neanderthals, who later lived in that very same cave, the researchers said. [Photos: See the Ancient Faces of a Man-Bun-Wearing Bloke and a Neanderthal Woman]

"We know from the genetic evidence that all humans that are alive today outside of Africa can trace their ancestry to the major dispersal out of Africa that happened between 70[,000] and 50,000 years before present," study lead researcher Katerina Harvati, a professor of paleoanthropology at the University of Tübingen in Germany, told reporters at a news conference.

Other earlier modern-human dispersals out of Africa have been documented at sites in Israel, including one based on the discovery of a 194,000- to 177,000-year-old modern human jaw from Misliya Cave and others tied to early human fossils dated to about 130,000 to 90,000 years ago at the Skhul and Qafzeh caves. But "we think that these early migrants did not actually contribute to modern humans living outside of Africa today, but rather died out and were probably locally replaced by Neanderthals," Harvati said. "We hypothesize this is a similar situation with the Apidima 1 [the newly dated modern human skull] population."

Discovery in Greece

The two ancient skulls were unearthed in the late 1970s by researchers at the Museum of Anthropology at the University of Athens. Given that the skulls were found in Apidima Cave, the researchers named them Apidima 1 and Apidima 2.

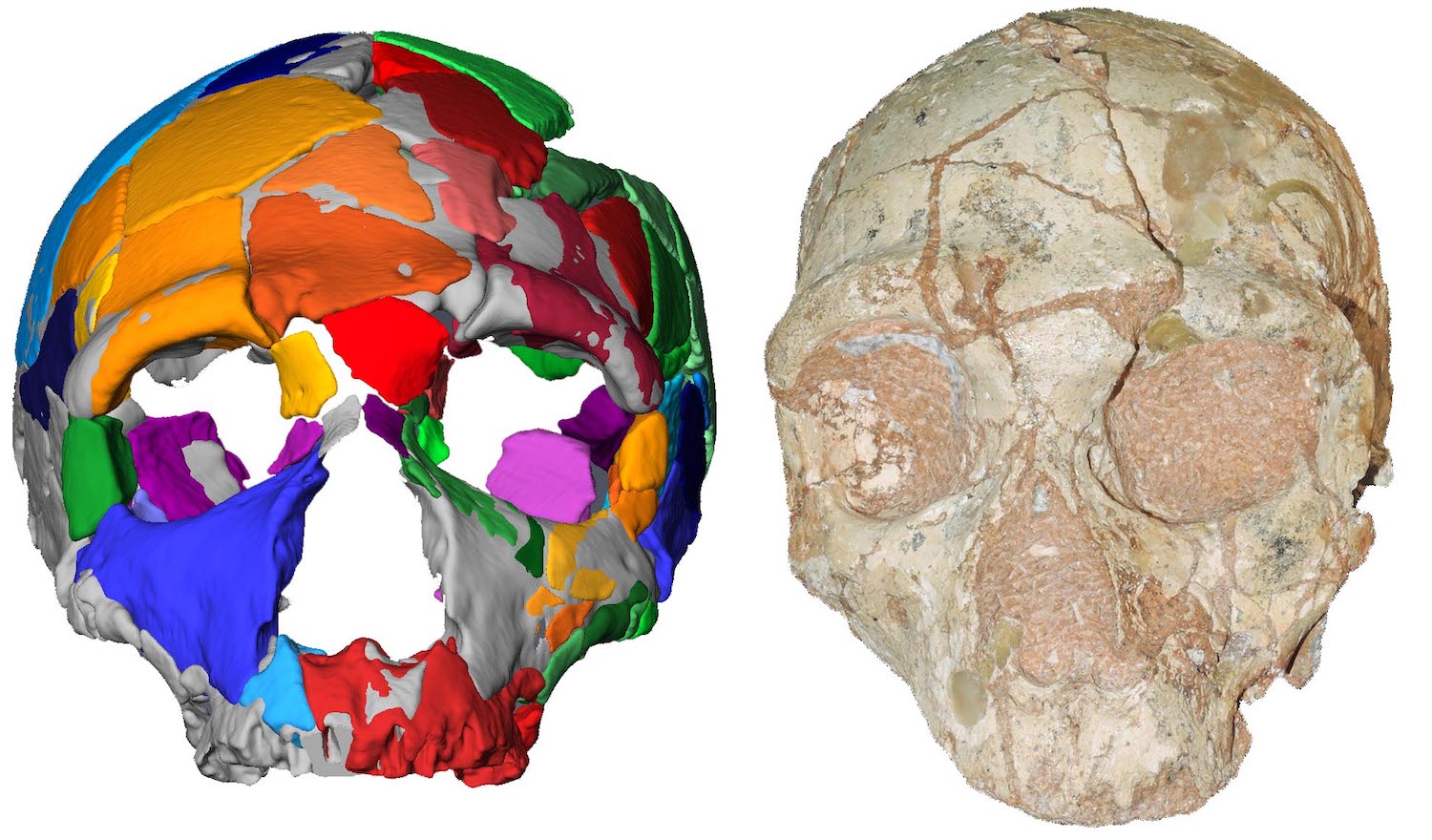

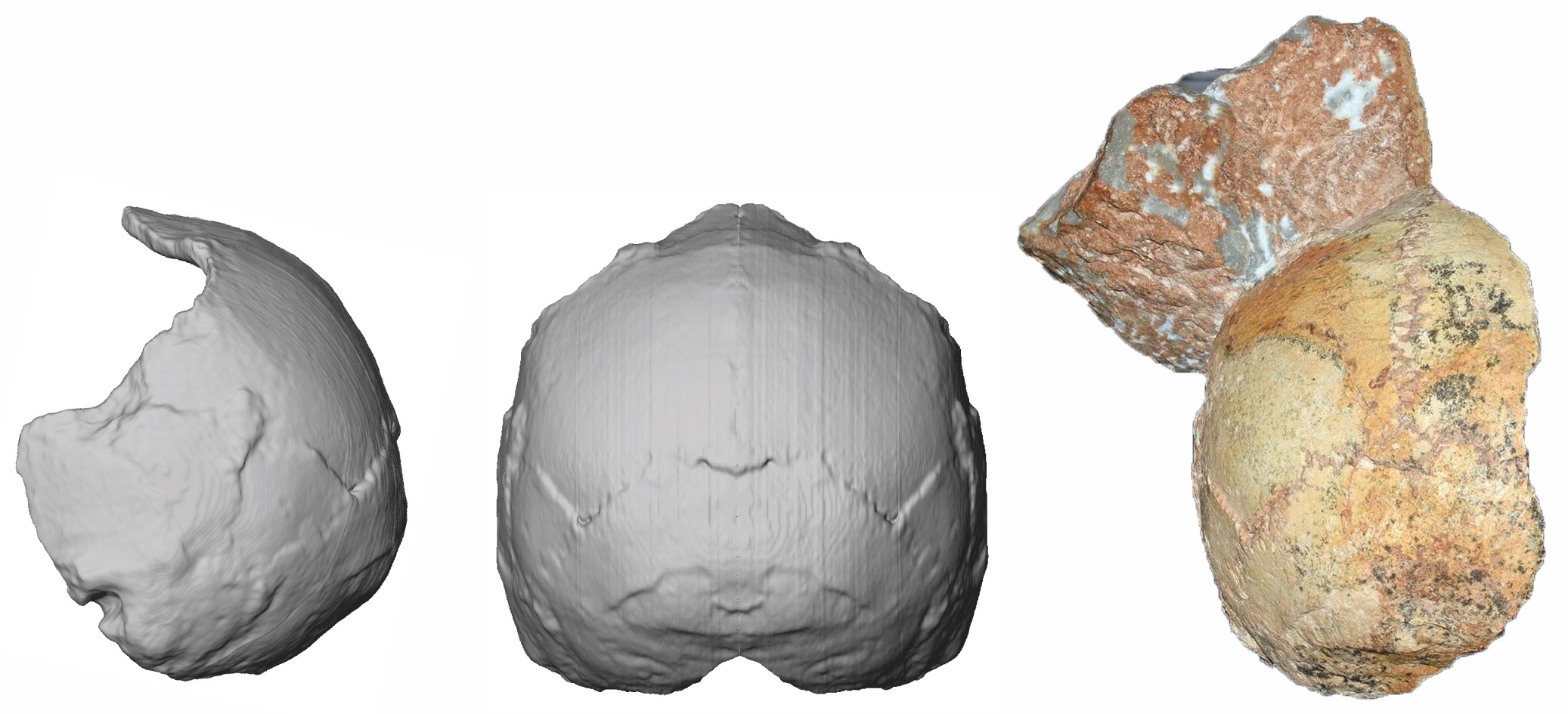

Both skulls, neither of which had a lower jaw, were found side by side in a block of breccia, angular pieces of rock that were cemented together over time. However, neither skull was in good shape; the damaged Apidima 1 included only the back of the skull, and at the time, researchers weren't sure what species it came from. Apidima 2, which preserved the facial region of the skull, was identified as Neanderthal, but it was broken and distorted.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For years, the skulls sat at the Museum of Anthropology in Athens until they were finally cleaned and prepared from the breccia block in the late 1990s and early 2000s. In the new study, Harvati and her colleagues put both skulls in a CT scanner, which generated 3D virtual reconstructions of each specimen. Then, they analyzed the features of each.

As in previous analyses, the team concluded that Apidima 2, which had a thick, rounded brow ridge, was from an early Neanderthal. Identifying Apidima 1 was more challenging because of its fragmentary remains, but the researchers were able to create mirror images of its right and left sides, which gave them a more complete reconstruction. [In Photos: Oldest Homo Sapiens Fossils Ever Found]

Several clues, such as the rounded back of the skull (a feature unique to modern humans), indicated that Apidima 1 was an early modern human, or Homo sapiens, the researchers said.

Dating the skulls

Next, the researchers dated the skulls. Previous analyses had estimated that the skulls were roughly from the same time period, given that they were discovered next to each other, suggesting that they lived around the same time. But by using a method known as uranium-series dating, the new team found that the skulls were not from the same time period.

At 170,000 years old, the Neanderthal skull fit within the range of other Neanderthal remains found in other parts of Europe. But the modern human skull was an unexpected outlier, predating the next-oldest H. sapiens remains in Europe by more than 150,000 years, the researchers found.

Uranium-series dating is one of only a few ways to date such ancient bones, "but it's not without some pitfalls," said Larry Edwards, regents professor in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences at the University of Minnesota, who was not involved in the study.

In effect, the method works because uranium decays into thorium. The more thorium there is in a sample, the older it is, Edwards told Live Science. However, bones and teeth don't contain much of their own uranium; rather, they absorb it from the environment over time. "That then requires you to make interpretations on how and when the uranium was picked up and whether or not the uranium was lost," he said.

But although this technique isn't ideal for dating skulls such as Apidima 1 and 2, it can still provide useful data, Edwards said.

"I think it's pretty solid, their [dating] conclusions," he said.

Out-of-Africa implications

Despite the skull's title as the "oldest known modern human fossil in Eurasia," the new finding does not rewrite the fundamentals of human evolution, said Eleanor Scerri, an associate professor and leader of the Pan-African Evolution research group at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, Germany, who was not involved in the study.

Those fundamentals are that humans first evolved in Africa and then ventured out into the rest of the world.

"The oldest human fossils still come from Africa and are about 100,000 years older than the Apidima fossil," Scerri told Live Science in an email. "That is roughly 4,000 generations — ample opportunity to move around."

That said, "if we want to ask questions specifically about the early history of our species in Eurasia, then this study may confirm the arguments made for multiple, early dispersals," Scerri said. In addition, this finding supports the view that the population of "early Homo sapiens was fragmented and dispersed," she said. [Top 10 Mysteries of the First Humans]

Previous studies have suggested that "Homo sapiens left Africa every time the Saharan and Arabian deserts shrunk, which happened broadly on 100,000-year cycles," roughly agreeing with dates from this study, she noted.

What's more, if modern humans truly had reached Eurasia by at least 210,000 years ago, then "we can no longer assume that 'Mousterian' stone tool assemblages found across large regions of Eurasia are necessarily being produced by Neanderthals," she said.

There are many avenues open to researchers hoping to learn more about the Apidima skulls. For instance, the skulls could contain ancient DNA or primordial proteins that could verify their species, Eric Delson, who was not involved with the research, wrote in an accompanying perspective published online today (July 10) in the journal Nature. Delson is a professor and the chair of the Department of Anthropology at Lehman College and The Graduate Center at the City University of New York.

Moreover, researchers could study the cave's paleo-environment and climate to figure out what conditions were like when Apidima 1 and 2 lived there. Today, the cave is on a cliff facing the sea, reachable only by boat, Harvati said.

The study was published online today in the journal Nature.

- In Photos: Bones from a Denisovan-Neanderthal Hybrid

- Photos: Newfound Ancient Human Relative Discovered in Philippines

- Photos: Looking for Extinct Humans in Ancient Cave Mud

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.