Space Archaeology Is a Thing. And It Involves Lasers and Spy Satellites

What does it take to be a space archaeologist? No, you don't need a rocket or a spacesuit. However, lasers are sometimes involved. And infrared cameras. And spy satellites.

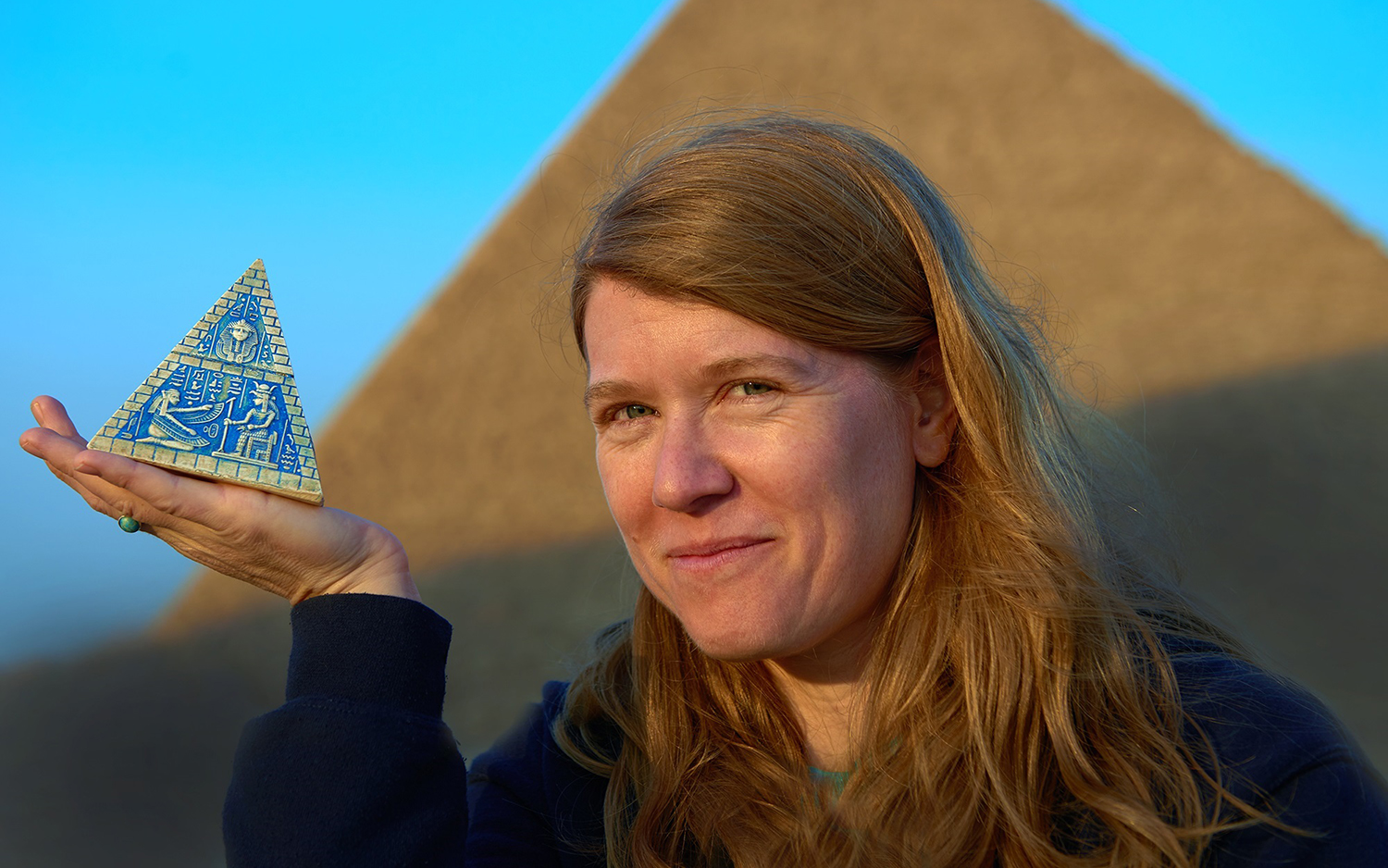

Welcome to Sarah Parcak's world. Parcak, an archaeologist and a professor of anthropology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, has mapped sites around the world from space; she does so using images captured by satellites — from NASA and from private companies — orbiting high above the ground.

From these lofty heights, sensitive instruments can reveal details that are invisible to scientists on the ground, marking the positions of walls or even entire cities that have been buried for millennia. Parcak unpacks how views from space are transforming the field of archaeology, in her new book "Archaeology From Space: How the Future Shapes Our Past" (Henry Holt and Co., 2019). [Read an excerpt from "Archaeology From Space"]

Satellites analyze landscapes and use different parts of the light spectrum to uncover buried remnants of ancient civilizations. But studying archaeological sites from above had very humble (and low-tech) beginnings, Parcak told Live Science. Researchers first experimented with peering down from a great height at a historic location more than a century ago, when a member of the Corps of Royal Engineers photographed the 5,000-year-old monument Stonehenge from a hot-air balloon.

"You could even see — from this very early and somewhat blurry photograph — staining in the landscape around the site, showing that there were buried features there," Parcak said.

Through the 1960s and into the 1970s, aerial photography continued to play an important role in archaeology. But when NASA launched its first satellites it opened up "a completely new world," for archaeologists in the 1980s and 1990s, Parcak said.

In fact, declassified images from the U.S. government's Corona spy satellite program, which operated from 1959 to 1972, helped archaeologists in the 1990s to reconstruct the positions of important sites in the Middle East that had since disappeared, eradicated by urban expansion.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Today, aerial or satellite images captured by optical lenses, thermal cameras, infrared and lidar — light detection and ranging, a type of laser system — are well-established as part of an archaeologist's tool kit. And archaeologists need as many tools as they can get; there are thought to be millions of sites around the world that are yet to be discovered, Parcak added.

But remote sensing isn't one-size-fits-all; different terrains require different space archaeology techniques. For example, in Egypt, layers of sand blanket lost pyramids and cities. In that type of landscape, high-resolution optical satellites reveal subtle differences on the surface that may hint at structures underground.

And in regions with dense vegetation, such as in Southeast Asia or Central America, lidar emits millions of pulses of light to penetrate beneath the trees and detect hidden buildings, Parcak explained.

In her own work, Parcak's analysis of satellite views led to the creation of a new map for the legendary city of Tanis in Egypt, famously featured in the movie "Raiders of the Lost Ark." Satellite images of Tanis revealed a vast network of the city's buildings, which had previously gone undetected even as the site was under excavation, she wrote.

If these stories of space archaeology in Parcak's book leave readers wanting more, they're in luck. An online platform called GlobalXplorer, launched and run by Parcak, offers users access to a library of satellite images for browsing and annotation.

Aspiring "citizen-scientists" can join "campaigns" to assist in the ongoing search for lost cities and ancient structures, and to help experts identify signs of looting in vulnerable sites, according to the platform website. Since 2017, approximately 80,000 users have evaluated 14 million satellite images, mapping 700 major archaeological sites that were previously unknown, Parcak said.

"Archaeology From Space" is available to buy on Amazon.

- 7 Amazing Places to Visit with Google Street View

- In Photos: Ancient Egyptian Tombs Decorated with Creatures

- Image Gallery: How Technology Reveals Hidden Art Treasures

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.