We Could Be Witnessing the Death of a Tectonic Plate, Says Earth Scientist

A gaping hole in a dying tectonic plate beneath the ocean along the West Coast of the United States may be wreaking havoc at Earth's surface, but not in a way most people might expect.

This gash is so big it may trigger earthquakes off the coast of Northern California and could explain why central Oregon has volcanoes, a new study found.

The researchers in the new study aren't the first to suggest that the Michigan-size Juan de Fuca (pronounced "wahn de fyoo-kuh") plate has a tear. But thanks to a new, detailed dataset, they're the first to say so with certainty. [The Science of Plate Tectonics and Continental Drift (Infographic)]

"Where other people had debated whether or not it [the tear] was there, we can pretty confidently say that it's real," study lead researcher William Hawley, a doctoral student in the Earth and Planetary Science Department at the University of California, Berkeley, told Live Science.

The Juan de Fuca plate is long, stretching about 600 miles (1,000 kilometers) along the Pacific Northwest coast, from Vancouver Island, Canada, to Cape Mendocino, California. "No part of it is above the water. It's a total oceanic plate" that's subducting, or diving beneath another plate, in this case the North American plate (a continental plate), Hawley said.

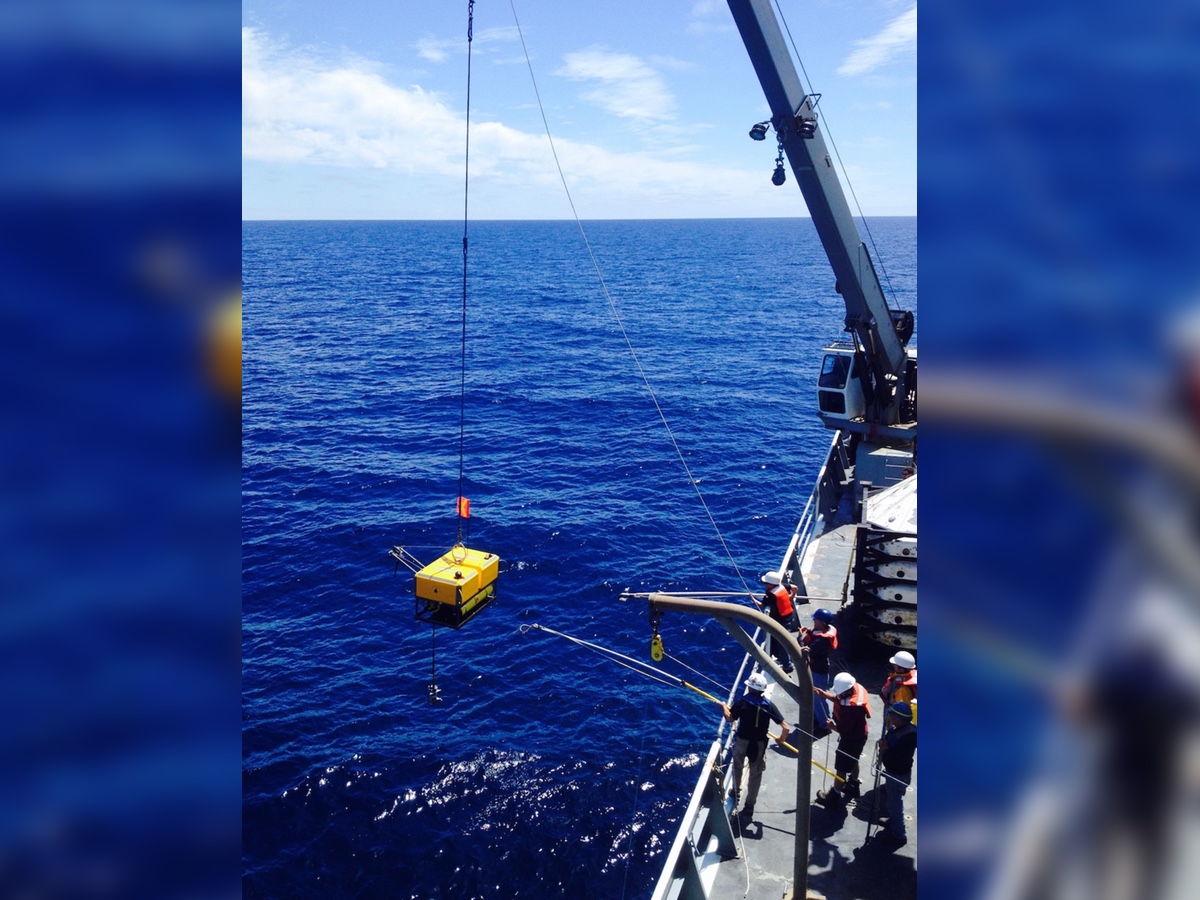

From 2011 to 2015, scientists boated out over different parts of the Juan de Fuca plate, dropped ocean-bottom seismometers underwater and let these sensors collect seismic data from earthquakes all over the world for a year.

When the year was up, the researchers returned, fished up the seismometers and uploaded the data, which allowed them to create a tomography, or layout, of the plate. Then, they deployed the devices to other spots on the plate. "It was an enormous community effort," Hawley said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The data from these seismometers showed how seismic waves traveled through the plate, which, in turn, revealed information about the plate's composition and varying temperatures. One region under central Oregon showed a gap in high-velocity seismic waves, which Hawley interpreted to be the hole.

But why does this hole exist? Hawley and study co-researcher Richard Allen, director of the Berkeley Seismological Laboratory, hypothesized that there is a weak zone in the Juan de Fuca plate that exists because the plate formed at two overlapping ridge segments. As this weakened zone of the oceanic plate goes under the continental plate, it unzips from the bottom up (from the underside upward), creating a gash.

"This tearing may eventually cause the plate to fragment, and what is left of the small pieces of the plate will attach to other plates nearby," the researchers wrote in the study. In other words, "we're witnessing the death of a plate," but it will take at least a few million years to die, Hawley said.

Hawley and Allen estimated that the hole is located at a depth of between 155 and 60 miles (250 and 100 km). The tear itself, which is narrower on top and widens with depth, is about 120 miles (200 km) wide. [Hidden Undersea Mountains Uncovered with Satellites (Photos)]

Moreover, it appears that material is getting pushed up through the tear, which may have led to the formation of the volcanoes in central Oregon's High Lava Plains about 17 million years ago, Hawley noted. In fact, it's incredible how many geographical and seismic features in the Pacific Northwest fit into the researchers' hypothesis, he said.

"The story links the hole in the tomography with this known weak zone in a plate and with a series of volcanic centers in Oregon and with a series of earthquakes and faults off the coast of Northern California," Hawley said.

The research is a "thought-provoking idea paper," said Ray Wells, a research geologist emeritus with the U.S. Geological Survey in Portland, Oregon, who was not involved with the study.

"I'm happy to see more data indicating a hole in the Juan de Fuca plate," Wells told Live Science in an email. "The coincidence of the hole with the location of a subducted zone of weakness in the Juan de Fuca plate is interesting and could help to produce a tear."

The study was published online July 11 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

- In Photos: The UK's Geologic Wonders

- Photos: Fiery Lava from Kilauea Volcano Erupts on Hawaii's Big Island

- Mount Etna: Photos of the Largest Active Volcano in Europe

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.