Alex: Where Will the Storm Go and How Long Will It Last?

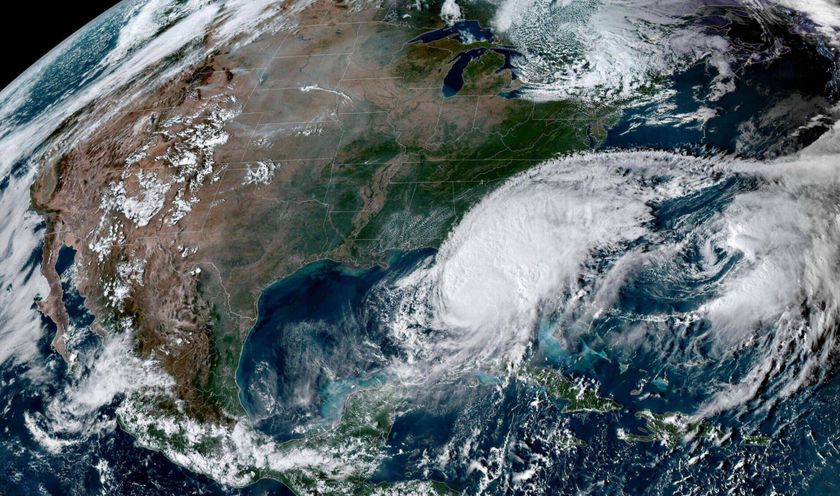

Tropical Storm Alex is expected to intensify into Hurricane Alex in the coming hours, and become the first hurricane of the season, according to NOAA.

As of 10 a.m. CDT on Tuesday, Alex was about 355 miles (571 km) southeast of Brownsville, Texas, and had top wind speeds of 70 mph (112 kph). Tropical storms whose wind speeds increase to more than 74 mph (119 kph) are designated as hurricanes.

Alex's path

Alex is expected to continue on its northwestward path, and is currently moving at 12 mph (19 kph). The storm should stay on this course, with a slow turn toward Mexico anticipated overnight or Wednesday, according to NOAA.

It is expected that the storm will make landfall late Wednesday night or in the early morning hours on Thursday, said Dennis Feltgen, a spokesperson for NOAA's National Hurricane Center in Miami. The storm will likely cross onto land in northern Mexico, just south of the Texas border.

"After it makes landfall, it will probably decay into a tropical depression by early Saturday morning," and will completely dissipate by Saturday afternoon, Feltgen said.

Between now and the time Alex makes landfall, NOAA scientists predict that the storm will intensify. Storms become stronger when they remain over warm water and when they are not subjected to wind shear or to the dry air pockets that sometimes infiltrate the Caribbean, said NOAA meteorologist Chris Landsea.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The science: Why storms intensify

Warm waters provide the energy for storms, and will fuel Alex's likely development from a tropical storm into a hurricane, Landsea said.

If a storm remains relatively stationary, its winds may drive mixing between warm surface waters and deeper, cooler waters, and result in the storm slowing down. But Landsea said this isn't likely to happen with Alex, which is steadily moving northward.

Wind shear can also cause storms to dissipate, but is unlikely to disrupt Alex, Landsea said. Storms are torn apart when the winds near the ocean surface and those near the top of the storm – about 8 miles (13 km) above the sea – are blowing in different directions, or at speeds that are different by at least 20 mph (32 kph).

Landfall also tends to weaken storms, although this effect greatly depends on the climate of the land the storm reaches, Landsea said. Storms are driven when water evaporates into the air and then condenses back from vapor into liquid – a process that releases heat energy. Because the evaporation rate over land is usually so much lower than over water, there is less energy to fuel the storm over land.

But the humid climates and moist soils of both Florida and Mexico's Yucatan peninsula can actually intensify small or medium-sized storms.

"These are flat, swampy lands," Landsea said. "They're surrounded on three sides by water, so a storm is still able to bring enough moisture to intensify it." The effect is different for full-blown hurricanes, though, which lose energy when they cross these regions.

But the region of northeastern Mexico where Alex will make landfall is much drier, and will break up the storm, Landsea said.

Dry air can also get entrained into storms, Landsea said, and weaken them. Saharan Air Layers, which are pockets of dry air that originate over the Sahara Desert and cross the Atlantic into the Caribbean, sometimes disrupt hurricanes. NOAA predictions do now show any of these pockets entering the air near Alex in the next few days, Landsea said, so are unlikely to affect this storm.

This article was provided by Life's Little Mysteries, a sister site to Live Science.