River Gets Blame for Giant 1811 Earthquakes

Massive earthquakes that struck the town of New Madrid, Mo., in 1811 can be traced to the actions of the mighty Mississippi River thousands of years earlier, a new study in the journal Nature suggests.

The work could affect scientists' understanding of the fault systems that caused the quakes.

Such mid-continent temblors have fascinated seismologists because they occur not at the points where tectonic plates interact — as the 2010 Haiti quake did — but in the center of plates. New Madrid lies atop the center of the North American Plate.

The new thinking works like this: At the end of the last ice age around 16,000 years ago, the Mississippi River washed away tons of soil, taking a giant weight off the central portions of the continent. Over 6,000 years, the river dredged 39 feet (12 meters) of sediment from the river basin — a "quite dramatic" erosion event that set in motion the events that would lead to the giant quakes, said geologist and study team member Roy Van Arsdale of the University of Memphis.

Where the sediment eroded, the earth buckled because of the released weight, just like a stick that is bent with two hands, said another team member, geophysicist Andrew Freed of Purdue University.

In the middle of the stick, Freed said, the upward curving top part is stretched and the bottom part is compressed. The land at New Madrid bent the same way as the sediment eroded. The area of land that was stretched contained faults, or cracks in the rocky plates of the Earth's crust. These faults were already close to rupturing, and when they eventually failed in 1811 they unleashed violent earthquakes.

The odds of repeating

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Unlike in the places where two pieces of the Earth's crust butt heads, an earthquake is unlikely to hit again anytime soon on the same faults in New Madrid, the study suggests. But other evidence may dispute this conclusion.

"The theory is certainly interesting enough to merit further consideration," Susan Hough, a geologist with the U.S. Geological Survey who was not involved with the work, told OurAmazingPlanet, but she added that geological evidence "suggests strongly" that a set of faults in the area has produced multiple earthquakes over the last 2,000 years (with quakes coming in roughly 500-year intervals), implying some regularity in these faults as well. More work is necessary to explain that, she said.

The study also suggests other faults in this zone may be close to failure and could erupt because of the sediment erosion, which means the danger zone could be more widespread than previously thought.

"We predict that whenever you have local erosion and uplift, you can have earthquakes," Freed told OurAmazingPlanet.

But scientists can't calculate the probability or severity of earthquakes at faults in the middle of tectonic plates, as they can for faults at plate boundaries.

Danger zone

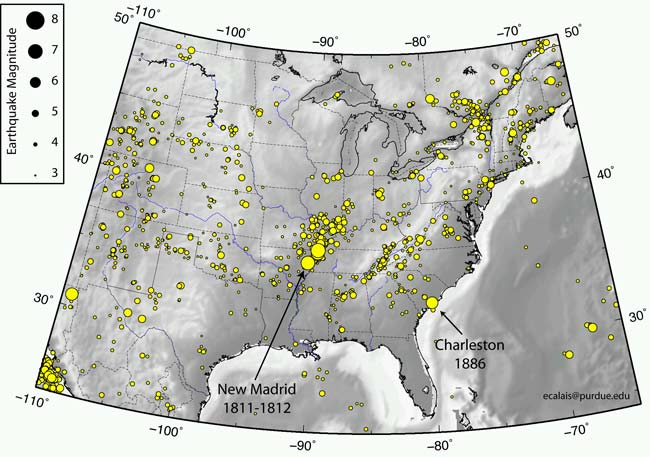

The New Madrid earthquakes that struck between December 1811 and February 1812 were some of the strongest seismic events ever recorded in the continental United States. The largest of these quakes was estimated between magnitude 7.0 and 8.0 and made the Mississippi River flow backwards temporarily. Earthquakes in this part of the country rumble over a larger area than they do on the West Coast, due to the makeup of the underlying ground. When the quakes hit New Madrid, according to legend, church bells rang in Boston.

The temblors ripped through the heart of the United States in the New Madrid Seismic Zone — the country's most earthquake-prone region outside California. The zone runs 100 miles (161 kilometers) along the Mississippi and borders eight Midwestern and Southeastern states: Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas and Missouri.

New Madrid still rumbles with roughly 200 tiny quakes annually — a 5.2-magnitude quake hit in 2008 — but a recent study suggested that what the town is feeling are actually 200-year-old aftershocks, since the fault may be shutting down. The New Madrid faults move more than 100 times more slowly than the San Andreas Fault; the slower a fault moves, the longer the aftershocks last. That's because the tectonic plates can't "reload" the fault, wiping out the effects of a previous earthquake and suppressing aftershocks.

- Top 10 U.S. Natural Disasters

- Earthquakes Rock in Synchrony, Study Suggests

- Image Gallery: Deadly Earthquakes

This article was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience.