Fossils of Earliest Animal Life Possibly Discovered

Fossils of what could be the oldest animal bodies have been discovered in Australia, pushing back the clock on when animal life first appeared on Earth to at least 70 million years earlier than previously thought.

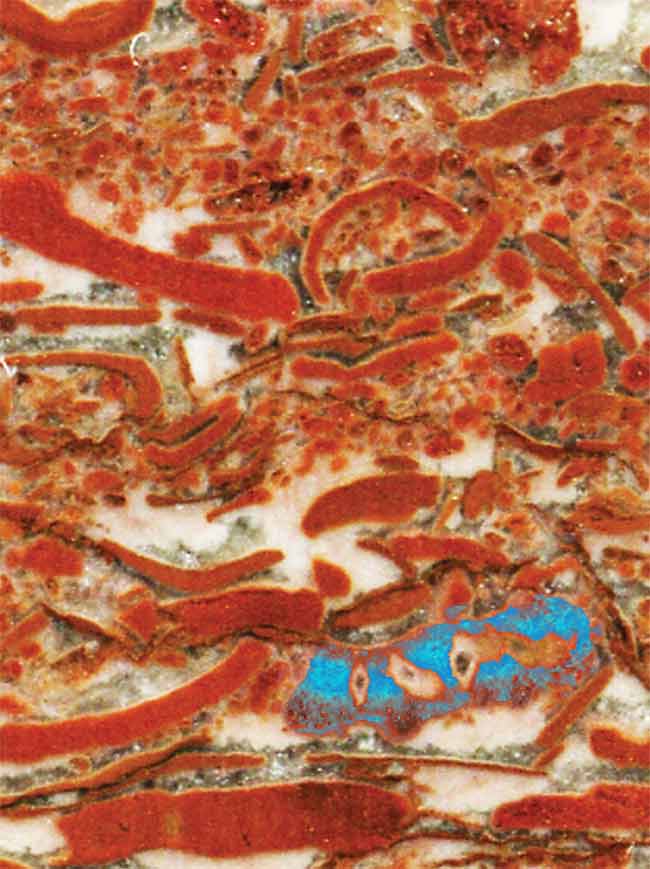

The results suggest that primitive sponge-like creatures lived in ocean reefs about 650 million years ago. Digital images of the fossils suggest the animals were about a centimeter in size (the width of your small fingertip) and had irregularly shaped bodies with a network of internal canals.

The shelly fossils, found beneath a 635 million-year-old glacial deposit in South Australia, represent the earliest evidence of animal body forms in the current fossil record. Previously, the oldest known fossils of hard-bodied animals were from two reef-dwelling organisms that lived around 550 million years ago.

Researchers have identified controversial fossils of soft-bodied animals that date to the latter part of the Ediacaran period between 577 and 542 million years ago.

The research was funded by the National Science Foundation's (NSF) Division of Earth Sciences.

Surpise finding

Princeton University geoscientists Adam Maloof and Catherine Rose spotted the fossils while working on a project focused on the severe ice age that marked the end of the Cryogenian period 635 million years ago.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

They spotted the fossils in the crevices between stromatolites, which are structures that form in oceans where the environment is too harsh for plants to grow and so cyanobacteria take over to form these microbial mats. Over time sediment piles on top, the microbes move back up to the surface and the cycle repeats until you get this sediment pile topped by bacteria.

"We're guessing the microbial mats made a reef-like substrate, and these sponges were probably growing on top, taking advantage of the reef height," Maloof told LiveScience.

Though the scientists aren't positive it's an animal, "that's our best guess," Maloof said. The organism is relatively large, so it likely wasn't something made by bacteria; it's asymmetric, suggesting it wasn't a higher animal like a worm; and it sported relatively large tunnels or canals, which resemble those found in sponges today. Algae have tubes that are much smaller than those in this fossil organism.

Today's sponges are equipped with tiny tubes that suck in seawater, which contains carbon they can eat. "And then to get rid of the water it's exhaled through the sponge and comes out of a series of larger tubes," Maloof said. The fossils showed this series of tubes that seem to be the exhaling type.

Snowball Earth

Their findings, published in the Aug. 17 issue of the journal Nature Geoscience, provide the first direct evidence that animal life existed before – and probably survived – the severe "snowball Earth" event that left much of the globe covered in ice at the end of the Cryogenian.

"We were accustomed to finding rocks with embedded mud chips, and at first this is what we thought we were seeing," Maloof said. "But then we noticed these repeated shapes that we were finding everywhere – wishbones, rings, perforated slabs and anvils. We realized we had stumbled upon some sort of organism, and we decided to analyze the fossils."

Maloof added, "No one was expecting that we would find animals that lived before the ice age, and since animals probably did not evolve twice, we are suddenly confronted with the question of how a relative of these reef-dwelling animals survived the 'snowball Earth.'"

Making 3-D images

Analyzing the fossils turned out to be easier said than done. The ancient skeletal fossils are made not of bone, but of calcite, which is the same material that makes up the rock matrix in which they are embedded. Therefore X-rays, which distinguish between different densities of bones, couldn't be used to look at the newly discovered fossils.

Maloof, Rose and their collaborators teamed up with professionals at Situ Studio, a Brooklyn-based design and digital fabrication studio, to create three-dimensional digital models of two individual fossils that were embedded in the surrounding rock.

When they began the digital reconstruction process, the shape of some of the two-dimensional slices made the researchers suspect they might be dealing with the previously discovered Namacalathus, a goblet-shaped creature featuring a long body stalk topped with a hollow ball. But their model revealed the creatures looked nothing like Namacalathus, but were rather sponges.

Previously, the oldest known and undisputed fossilized sponges date to around 520 million years old.

In future research, Maloof and his colleagues intend to automate the three-dimensional digital reconstruction technique to increase the speed of the process.

(Editor's Note: This story was updated at 3:45 p.m. to include comments and context from the study researcher.)

- 25 Amazing Ancient Beasts

- Image Gallery: Small Sea Monsters

- Image Gallery: Dinosaur Fossils

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.