7,000-year-old cult site in Saudi Arabia was filled with human remains and animal bones

Animal and human remains were excavated from a mustatil, an ancient desert monument believed to have been used for ritual practices in Saudi Arabia.

Archaeologists in Saudi Arabia have discovered ancient human remains buried near hundreds of scattered animal bones inside a 7,000-year-old desert monument, a ritual site used by a prehistoric cult.

The remains, those of an adult male approximately in his 30s, were found inside a mustatil, a structure that takes its name from the Arabic word for rectangle. The ruin is one of more than 1,600 mustatils discovered in Saudi Arabia since the 1970s. Mostly submerged beneath sand, the structures were built when the Arabian Desert was a lush grassland where elephants roamed and hippos bathed in lakes.

The mustatils' builders were members of an unknown cult. As a change to the climate slowly transformed the land to desert, cult members likely gathered to protect it by sacrificing their cattle to unknown gods, researchers say. Now, a new mustatil excavation, detailed in a study published March 15 in the journal PLOS One, has revealed more details about the mystifying structures and their worshippers lost to time.

"Almost nothing has been written on the mustatils and beliefs that surrounded them," study lead author Melissa Kennedy, an archaeologist at the University of Western Australia, told Live Science. "Only 10 mustatil have been excavated, and this study is one of the first to be published. So we still don't know a lot about this tradition yet."

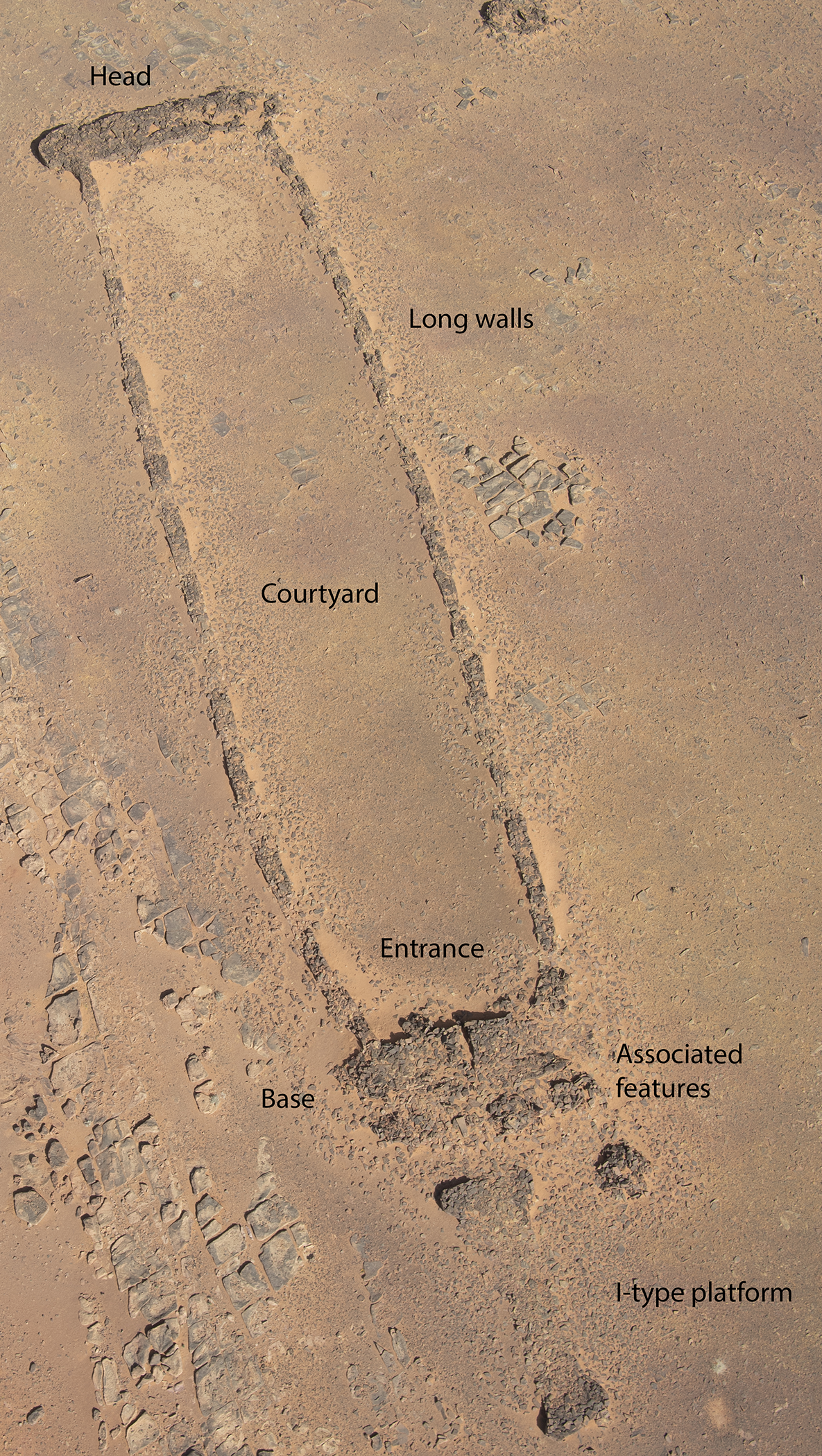

Mustatils vary in their appearance, but they are typically long rectangles formed from low rock walls around 4 feet (1.2 meters) high. Excavations have revealed complex structures inside some of the ruins, including interior walls and pillars that give way to central chambers possibly reserved for feasting and ritual sacrifices, Kennedy said.

Related: Vast 4,500-year-old network of 'funerary avenues' discovered in Saudi Arabia

Worshippers entered the mustatils from one end and walked anywhere from 66 to 1,970 feet (20 to 600 m) or more to the other, arriving at a rubble platform called the head. A chamber inside the head housed a beytl — a sacred stone, sometimes originating from a meteorite — that cult members used to commune with their gods.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The mustatil excavated by the researchers, located 34 miles (55 kilometers) east of the ancient city of AlUla, is 460 feet (140 m) long and constructed from local sandstone. Its beytl is a large upright stone, around which the researchers found 260 fragments of animal skulls and horns. The bone pieces are mainly from domesticated cattle, though the researchers said some fragments belonged to domesticated goats, gazelle and small ruminants.

"They would most probably have brought animals with them, potentially slaughtered them on-site, offered the horns and upper parts of the skull to a deity, while potentially feasting on the rest of the remains," Kennedy said. "We can't be certain if the slaughter occurred on-site or somewhere else, as we haven't found the rest of the animal remains. However, we think that it most probably occurred on-site, as the horns, particularly the keratin — which degrades very quickly — were in such good condition. It suggests that there was probably only a short period of time before the removal of the horns and their offering in the mustatil."

Immediately to the north of the mustatil's head, the researchers found a cist, a type of burial chamber built throughout the Neolithic and Bronze ages across Europe and the Middle East. Analysis of the interred bones belonging to the man revealed that he was in his 30s or early 40s when he died and that he probably had osteoarthritis, a degenerative joint disease that is the most common form of arthritis. Radiocarbon dating of the human and animal bones showed that the man was buried 400 years after the animals had been slaughtered — a sign that the mustatils were sites of repeated pilgrimages.

"We are finding more and more evidence for humans being interred in mustatils," Kennedy said. "However, these burials are always later; they do not date to the same time period as the animal offerings. We hypothesize that the mustatil sites retained their importance even after their use ceased and that later generations would bury their dead at these places as a way of asserting ownership over these structures, essentially claiming a link with the past."

The purpose of the mustatils' ceremonies remains an enigma. As the desert-spanning structures were built during the Holocene Humid Period — a phase that lasted between 7000 B.C. and 6000 B.C. for Arabia, making it and North Africa much wetter but still prone to droughts and slow desertification — the researchers think there could be some connection between the rituals practiced inside these structures and a communal desire to bless the drying land with rain.

They are now testing this hypothesis by geographically mapping the close placement of mustatils to prehistoric pastoral lands, rivers and lakes. The investigation, which is ongoing, could reveal the connections between ancient religious practices and the region's primeval climate crisis.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.