Baby Dino Skeleton Sheds Light on Growth

A new fossil of a juvenile dinosaur that lived 140 million years ago is shedding light on how the ancient reptiles grew from youngsters to enormous adults.

Scientists unearthed the dinosaur in 1999 from the Lower Morrison Formation of the Howe Ranch in Bighorn County, Wyoming. They estimate the dinosaur was about 1 year old when it died toward the end of the Jurassic Period (206 million to 144 million years ago).

“It’s the only complete skeleton of a juvenile sauropod we know of,” said lead researcher Daniela Schwarz of the Natural History Museum in Basel, Switzerland.

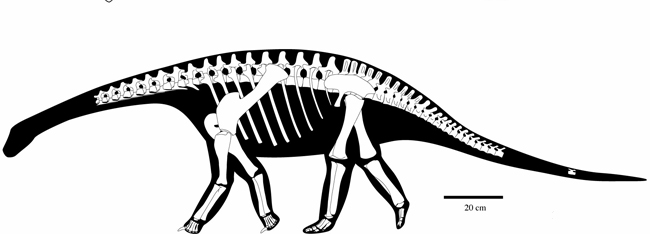

The 6-foot-long dinosaur is a sauropod that belonged to the family Diplodocidae, which included four-legged vegetarians equipped with long, slender tails. Past research has suggested the diplodocids used their tails as whipping weapons. One study found that Apatosaurus louisae could crack its tail at supersonic speeds to produce a ground-shaking boom.

“We do not know very much about sauropods of this age,” Schwarz said. “So it’s not clear how much they change when they grow, and that makes comparisons [with adults] very difficult.”

The skeleton is actually missing a tiny portion—the end of the tail—so the scientists can’t say with accuracy whether the juvenile also possessed the whiplash tail.

An adult Apatosaurus louisae reached a shoulder height of nearly 10 feet, with a nose-to-tail length of 60 feet, whereas the newfound juvenile dino was only about two feet tall at the shoulder.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The juvenile’s limb bones show similar proportions as those of adult diplodocids. However, its relatively short neck and lengthy mid-section don’t match those of its full-grown relatives. “The vertebrae column gets shorter during growth, so the adult specimens have shorter trunks, for example, than the juveniles, at least in this species,” Schwarz told LiveScience.

Plant remains found at the site indicate that the dinosaur perished in a watering hole “deathtrap” in an ancient swampland.

“The locality represents sort of a swampy environment where dinosaurs came and drank,” Schwarz said. One possibility is that while drinking, “they were caught in the swamp sediments and they died.”

The research is detailed in the latest issue of the journal Historical Biology.

Editor's Note: Images used with permission. Journal citation: Historical Biology, Volume 19, Issue 3 September 2007 , pages 225 - 253.

- Image Gallery: Dinosaur Art

- Vote: Avian Ancestors: Dinosaurs That Learned to Fly

- A Brief History of Dinosaurs

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.