Brain Surgery: It Really Is Brain Surgery

This Behind the Scenes article was provided to LiveScience in partnership with the National Science Foundation.

Everything changes after the surgeons open your skull.

Your brain, and the tumor inside it, no longer fully float in their protective bath of cerebrospinal fluid. Gravity comes into play, as does the atmospheric pressure of the operating theater. The brain responds to these foreign forces, the cerebral tissue sagging, rebounding and changing shape. The tumor that the neurosurgeons want to remove also has changed position.

The preoperative MRI image is no longer accurate enough for brain surgery.

Thus, the brain the surgeon operates on is a different shape from the one depicted in the preoperative MRI. Of course, once the surgeon begins work, the shape of the brain changes even more.

The brain’s changing shape is a problem not only of space, but of time. The goal is to remove as much as possible of the tumor and none of the healthy neural tissue. Today’s operating procedure is to keep track of the brain’s movement by conducting MRI scans during surgery. MRI—magnetic resonance imaging—is a labor-intensive and painstaking process that takes time. Processing each intraoperative MRI can put the procedure on hold for as long as 90 minutes.

“They tell me that they don’t even talk while the MRI is happening,” said Nikos Chrisochoides, a professor of computer science at the College of William and Mary in Virginia.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Chrisochoides is the leader of a group that is working with a team at Harvard Medical School to use mathematics and computer power to solve the neurosurgeon’s problem of space and time.

Modeling the brain

In essence, the William and Mary team provides the surgical team with a dynamic computer model of the patient’s brain. In clinical trials, Chrisochoides says his team can render a new model in six or seven minutes, but hopes to be able to do so in under two minutes.

“We want to help the neurosurgeon make an informed decision of what to cut, where the critical paths are, what areas to avoid,” he said. “I’m neither a neurosurgeon nor a doctor, so the contribution of my research is to make this distillation of objects really, really, really fast.”

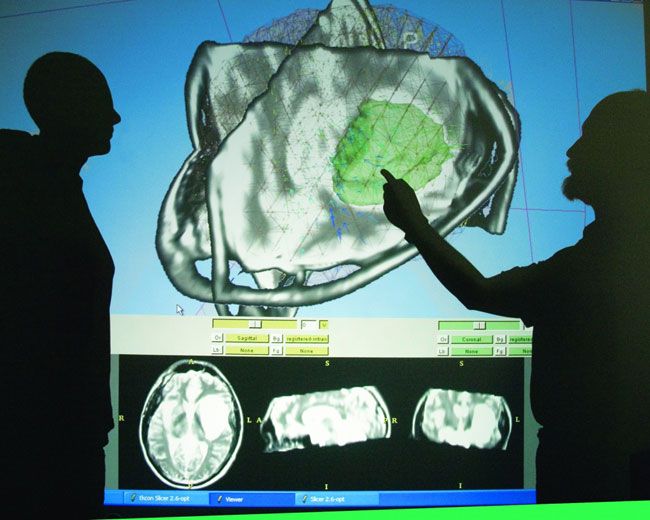

Chrisochoides’ lab is dominated by a projection computer monitor whose screen would not look out of place in a small multiplex theater. Chrisochoides handed out 3-D glasses to a small audience that included a colleague from NASA and Andriy Fedorov, a Ph.D. student recently returned from 15 months as the team’s representative at Harvard.

Chrisochoides takes his place at the keyboard and mouse and the huge monitor displays a parietal slice of a computer mesh brain. A nasty-looking blob clearly indicates the presence of the tumor. The glasses give the audience a striking 3-D effect, showing off the curves of the vector arrows indicating how displacement—represented by color as well as length of the shaft—were acting on the brain.

The process begins with the acquisition of a variety of images before the surgery, which are otherwise unavailable in the middle of the procedure. Low-resolution intraoperative data allows the tracking of the shift of brain matter and calculates how to change the preoperative images accordingly.

Only a guess …

The brain, of course, is an elastic object.

“If you push it,” Chrisochoides said, “it takes energy and then after a while it settles down. We can calculate the place where it settles by solving the partial differential equation. Mathematicians can tell us that there is a solution, but they cannot tell us what the solution is. There’s no such thing for this equation. There’s no analytic solution. So we have to approximate.”

Chrisochoides approximates the geometry of the patient’s brain by tessellation—dividing it into triangles in three dimensions, or in other words, generating a mesh representing the brain. It’s work that NSF has funded for the past seven years he has been at William and Mary, and earlier this year, Chrisochoides’s work earned him a prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship.

“This Fellowship means quite a lot to my research,” said Chrisochoides. “It is in medicine and health, not computer science as one would expect, and it will open many more opportunities for our project.”

The funds will establish a new Center for Real-Time Computing at William and Mary and drive the design of three new courses on medical image analysis, something Chrisochoides will undertake as he begins writing the first book on parallel mesh generation.

“I’m delighted to see his success in terms of his scientific work and societal impact and the recognition he received,” said Frederica Darema, one of the NSF officers who has overseen Chrisochoides’s efforts. “This is a great example of how computer sciences research is impacting other fields and enables such important capabilities, and it’s really great to see this impact in medicine.”

Editor's Note: This research was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF ), the federal agency charged with funding basic research and education across all fields of science and engineering.