Incredible Fish Armor Could Suit Soldiers

African fish that have trolled for prey in murky freshwater pools for nearly 100 million years sport the best of the best in body armor. Now a team of engineers has dissected the aquatic armor, figuring out how it works in an effort to suit up future soldiers.

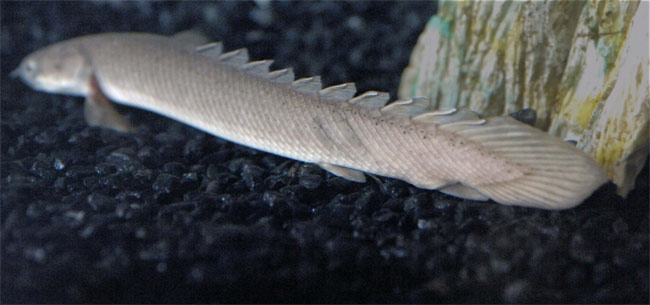

The armor of the fish, Polypterus senegalus, is so effective because it is a composite of several materials lined up in a certain way, the engineers state in a their analysis detailed in the July 27 issue of the journal Nature Materials.

"Such fundamental knowledge holds great potential for the development of improved biologically inspired structural materials," said lead MIT researcher Christine Ortiz, "for example soldier, first-responder and military vehicle armor applications."

The fish's shield would've been particularly critical in the past, when it had to fight off members of its own species along with the likes of typical predators, such as giant sea scorpions with biting mouth parts, grasping jaws, claws and spiked tails. An extinct aquatic enemy, the ancient armored fish, Dunkleosteus terrelli, could have bitten through the exoskeleton of its prey and munch on the flesh beneath.

Today, though the armor may be overkill, it protects the fish from its own species and other carnivores in the water.

With funding from the U.S. Army, the engineers measured the material properties of a single fish scale and its four layer materials, including bone and dentine (a major mineral in teeth).

The different chemical properties of each material, the shape and thickness of each layer and the junctions between layers all contributed to the armor's strength.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"That doesn't surprise me that millions of years or hundreds of millions of years of evolution would be a good starting point for what we need for this day and age," said Leo Smith, assistant curator of zoology at The Field Museum in Chicago, who was not involved in the study. "[The armor's] been sort of fine-tuned during that time for different aspects."

- Video: A Surprising Fish Tale

- Amazing Things You Didn't Know About Animals

- Images: Freaky Fish

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.