Why Dinosaurs Ruled: Just Plain Luck

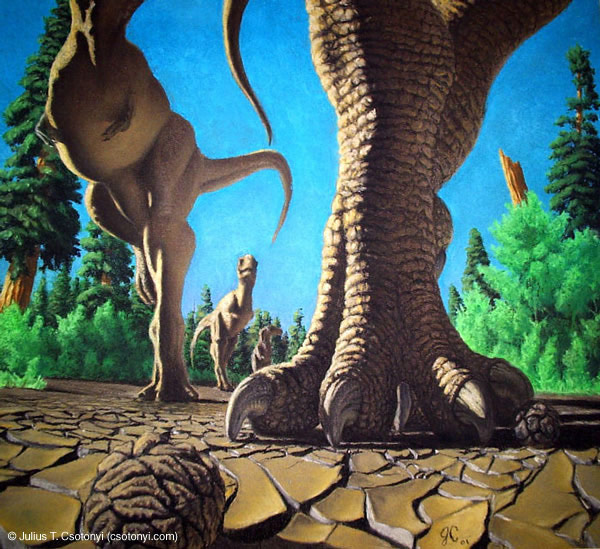

Dinosaurs are often seen as unlucky, having been wiped out by an asteroid. But they dominated Earth for more than 160 million years, evolving into a wild array of body types and sizes suited for many different ecological niches. Scientists previously thought that it was this evolutionary diversity that enabled the dinosaurs' reign, allowing them to out-compete similar groups of reptiles, but a new study, detailed in the Sept. 11 issue of the journal Science, shows that it was really just a matter of luck. "For a long time it was thought that there was something special about the dinosaurs that helped them become more successful during the Triassic, the first 30 million years of their history, but this isn't true," said lead author of the study, Steve Brusatte, a Ph.D. student at Columbia University and affiliate of the American Museum of Natural History in New York. The closest competitors to the dinosaurs during the Triassic period (about 251 to 199 million years ago) were the crurotarsans, the ancestors of today's crocodiles. Both dinosaurs and crurotarsans evolved and filled some of the same ecological niches after a massive extinction event at the end of the Permian period some 250 million years ago. Both groups also survived a later extinction event about 228 million years ago. But only the dinosaurs (and crocodiles) made it through a period of rapid global warming at the end of the Triassic 200 million years ago. And avian dinosaurs are still with us today in the form of modern birds, which evolved from theropod dinosaurs and survived a separate and later mass extinction event at the end of the Mesozoic Era. Special or lucky? To see if there was indeed something "special" about the non-avian dinosaurs that allowed them to out-compete the crurotarsans, Brusatte and his colleagues compared the reptiles' rates of evolution and morphological disparities — or range of different body plans. The team used a database of 437 features from 64 skeletons and relied on a new family tree of the group Archosauria, which includes non-avian dinosaurs and crurotarsans, as well as pterosaurs, modern birds and crocodilians. The research was funded by the Marshall Scholarship and the Paleontological Society. The researchers found no difference in the rates of evolution of the two groups. If dinosaurs were out-competing the crurotarsans, they should have been evolving faster. Crurotarsans also had a much higher disparity — in other words, they were exploring a wider range of body types, diets and lifestyles. Again, this should have given them a leg up on the dinosaurs. "If any of us were standing by during the Triassic and asked which group would rule the world for the next 130 million years, we would have identified the crurotarsans, not dinosaurs," Brusatte said. The dinosaurs only surpassed the crurotarsans when the latter were killed off at the end of the Triassic and the dinos no longer had to compete with them. So why did the dinosaurs survive that second mass extinction event, while the crurotarsans (except for a few lineages of crocodiles) disappeared? "We don't know the answer to that," Brusatte said, "but we suspect that it was nothing more than luck, plain and simple."

- Dino Quiz: Test Your Smarts

- Birds of Prey: Spot Today's Dinosaurs

- Images: Dinosaur Fossils

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.