In Tough Times, Even Amoebas Turn to Family

When times are tough, many of us turn to family and develop closer ties. So too with amoebas.

Some of these single-celled organisms tighten family bonds and cooperate when food is in short supply, new research shows.

The research, published this week in the journal PLoS Biology, shows how one amoeba species can distinguish genetically similar individuals, and how an incredibly simple life-form can display some sophisticated, social behaviors. (Not only is an amoeba a single cell, it reproduces asexually. So one parent cell divides into two daughter cells, which can continue to divide and produce more amoebas.)

"These single cells aggregate based on genetic similarity, not true kinship," said researcher Gad Shaulsky, professor of molecular and human genetics at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. Shaulsky added that this demonstrates a discrimination between "self" and "non-self" that is similar to that seen in the immune systems of higher organisms.

Amoeba community

Called Dictyostelium discoideum, this amoeba species generally keeps to itself when living in a healthy environment with enough grub.

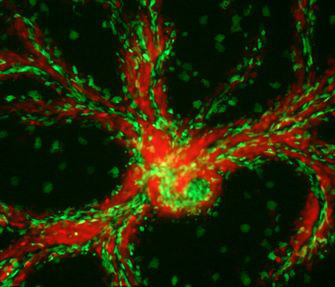

But when food supplies run low, the free-living organisms clump together into a community of individuals. The result is a multi-cellular organism. Each amoeba takes on one of two roles in this organism: They either become spores, which can survive and reproduce, or they die and the dead cells forms stalks that lift the spores above the ground to increase the chances the spores will disperse to more favorable environments.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Only cells that form spores can pass on their genetic information to future amoebas. So the preferred position is spore. About 20 percent of the cells, however, do turn into stalks.

Previous research has shown that Dictyostelium cells sometimes cheat and ditch stalk duty. Instead, they turn into spores while reaping the benefits (passing on genes) provided by other stalks.

Chummy cells

Perhaps there's a way to avoid being cheated, the researchers wondered. If being a stalk means one amoeba could ensure the survival and success of genetically similar individuals, evolutionarily, it makes sense to take one for the family.

To find out, the researchers mixed cells from genetically distinct strains of the amoebas. They found that the amoebas segregated into clusters of genetically similar individuals once they congregated into a multi-cellular formation.

In this way, the researchers determined that Dictyostelium reduces the likelihood that it will become a stalk cell that will die to assist in the survival of a genetically distant individual.

"The big thing we found is that Dictyostelium discoideum have social behavior," said researcher Mariko Katoh of Baylor College of Medicine. "We didn't really know if they could discriminate when the genetic differences were small. That was the surprising part."

Amoebas, along with plants, animals, protists and fungi, are considered eukaryotes by biologists. Sociality has also been detected among the other major group of organisms, prokaryotes (bacteria and archaea), which are generally single-celled organisms.

The amoeba research was funded by the National Science Foundation and the Keck Center for Interdisciplinary Bioscience Training of the Gulf Coast Consortia.

- Even the Simplest Creatures Favor Family

- The Invisible World: All About Microbes

- Amazing Animal Abilities

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.