Before Flowers, Odd Bugs Pollinated Plants

Before there were flowers, pollination of plants by insects was likely rare, and scientists had no idea of the insect culprits. But a new discovery suggests at least one flittering pollinator.

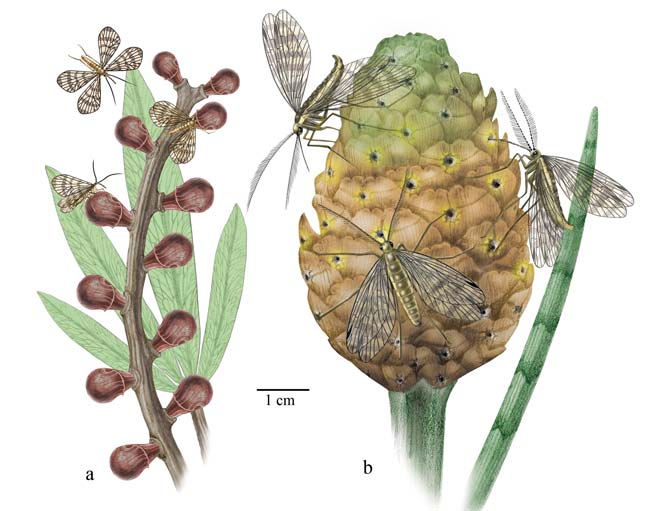

Strange-looking insects called scorpionflies may have slurped up plants' nectar-like fluids through long, tube-like snouts, well before the evolution of flowering plants and the insects that pollinate them, researchers report.

The finding could change how scientists think about pollination of plants by animals, which is thought to have evolved as flowering plants called angiosperms came onto the scene during the late Cretaceous, or about 99.6 million to 65.5 million years ago.

(Pollination occurs when either the wind or an animal, mostly insects, deliver pollen from a plant's male reproductive organ to the female parts either on the same plant or another one.)

Way back when, most non-flowering plants called gymnosperms were wind pollinated, paleobotanists have thought. And if animal pollination did exist in ancient gymnosperms, scientists assumed it was rare and unspecialized.

"Back when there were no angiosperms, before the mid to early Cretaceous, all we had were these gymnosperms with tubes and funnels, some quite jerry-rigged to affect insect pollination," study researcher Conrad Labandeira of the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Natural History told LiveScience.

Even so, Labandeira and his colleagues found insects were equipped with custom features made for such seed plants.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

These results come from an examination of fossils from 11 extinct species of scorpionflies (from three different families) that lived during the Mesozoic, which lasted from 251 million to 65.5 million years ago. Such insects have elongated heads that resemble snouts and are tipped with mouthparts. The male's genitalia curve up over the back like a scorpion's tail — and hence the name.

The insect specimens included flattened fossils preserved beneath overlying sediment and one preserved in amber.

The researchers found such scorpionflies sported long, tubular mouthparts up to a half inch (1.3 cm) in length that were either hairy or adorned with angled ridges and many of which were tipped with sponge-like pads for fluid uptake. The features seemed to be specialized for sucking up nectar-like pollination drops from five extinct gymnosperms.

The only missing piece of evidence: preserved pollen grains. Labandeira said such evidence may have been destroyed over time due to oxidation.

The results are detailed in the Nov. 6 issue of the journal Science.

- Top 10 Poisonous Plants

- More Insect News, Information & Images

- How Plants Know When to Flower

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.