Fickle Female Fish Force Males to be Flashy

Working with evolution, fussy female fish have caused desperate males to blush bright red or take on a victorious blue-ribbon shade of indigo.

Two species of cichlid fish swimming in East Africa's tropical Lake Victoria are brilliantly hued because females chose the brightest male partners, according to new research.

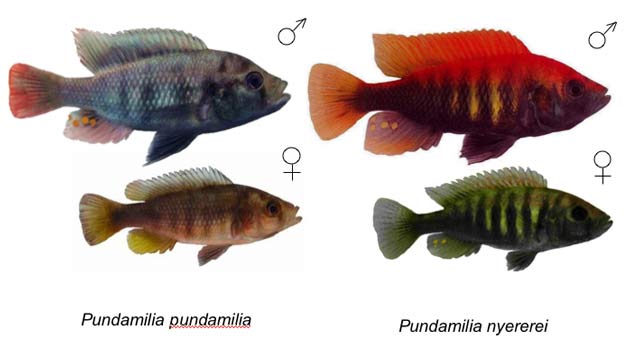

Although the females of both species resemble each other, with drab gray-brown coloring, the males look completely different.

Separated by color

The males of one species, Pundamilia pundamilia, are metallic blue. They eat insect larvae in the shallows.

The Pundamilia nyererei males are bright red and yellow. They feed on zooplankton and spend most of their time in deeper water.

Habitat depth and color have become linked. Blue light is absorbed by water, and only the red makes it effectively to deep water. So the fish's eyes have adjusted by species. The blue variety in shallow water see blue better, while the red ones in deeper water are more sensitive to red.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"At the same time, females in this population developed a preference for brightly colored, conspicuous males," said evolutionary biologist Martine Maan from the University of Leiden in The Netherlands. "Males of other colors are inconspicuous and unattractive, and therefore produce few offspring. We think that as a result of this, eventually only the bright red and bright blue fish remained, and two separate species would arise. Now that the two species do not interbreed anymore, the differences between them may increase and new differences may accumulate."

Maan's research will be detailed in the June issue of the journal the American Naturalist.

Not just sexy

Colors do more than boost a male's sex appeal.

It turns out vibrant males are the healthy choice. Maan discovered the brightest males of both species carry fewer parasites. Similar pickiness has been found at work in other species, and even people use beauty cues to pick healthy, promising partners.

Hues can also determine a territorial prizefighter. In a match between a blue and a red male, researchers at the University of Groningen found that red males dominate the competition.

However, colors lose all of their luster when the lake is murky.

The cloudier the water, the harder it is for the females to find the brilliant males. When light is dim, females stop picking the bright males and choose the biggest ones instead, because size is an easier feature to pinpoint than color.

Getting back together

In unclear water, as females start being less picky and selection for male traits becomes less species-specific (blue or red, for example). The differences between species grow less obvious and breeding between species becomes more common.

"If a female makes 'the wrong choice,' her offspring will probably have characteristics that are intermediate between the two species," Maan told LiveScience. "We expect these hybrids will be less successful than the 'pure' species, because they are not adapted to either one of the two environments."

Colorful cichlid species are swimming in troubled waters.

To maintain the number of cichlid species in Lake Victoria, the fish must be able to choose the best mates with rich coloration, and to do that they must be able see. But the introduction of Nile perch, deforestation and population growth is muddying the lake.

"My work emphasizes that the maintenance of the Lake Victoria species diversity crucially depends on measures that counteract the ongoing eutrophication," Maan said.

- Why We Have Sex: It's Cleansing

- Rumor or Reality: The Creatures of Cryptozoology

- Men Pay the Ultimate Price to Attract Women

- GALLERY: Rich Life Under the Sea