Exorbitant Fees Offered to Human Egg Donors, Study Finds

Fertility companies are paying egg donors high fees that often exceed guidelines, especially for donors from top colleges and with certain appearances and ethnicities, a new study finds.

The upshot: Parents with infertility problems are willing to pay up to $50,000 for a human egg they hope will produce a smart, attractive child.

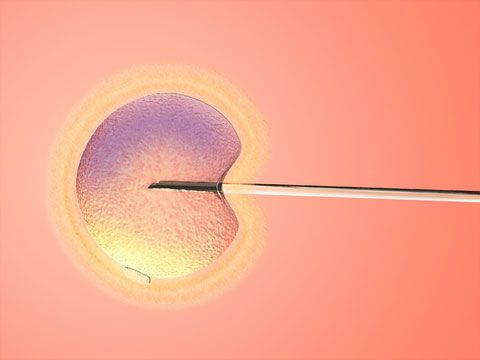

The first baby conceived through egg donation was born in 1983. Since then, the practice, which involves transferring fertilized eggs from a donor into a woman's body, has grown dramatically. The rise has been seen particularly among women with ovarian failure, women over 40, and gay men who want to have children through surrogate pregnancy.

While there are few government regulations controlling the use of this technology, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM), a professional organization, has issued guidelines. The ASRM ethics committee recommends limits on the amount of money egg donors should be paid, saying "sums of $5,000 or more require justification and sums above $10,000 are not appropriate."

Yet the recent study found that out of more than 100 egg-donor ads from 300 college newspapers, about half offered fees above $5,000, with a quarter of the ads touting payments exceeding the $10,000 limit.

SAT scores matter

The study also found that the advertised fees correlated with the average SAT score (standardized test used for college admissions) at the college where the ad was placed, which suggests agencies are paying more to donors who appear more intelligent. This too is a violation of the guidelines, which state that compensation should not vary according to donors' "ethnic or other personal characteristics."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The guidelines were set up to avoid ethical dilemmas associated with putting a price on the seeds for human life, according to the ASRM. And scaling that price based on certain human genetic material that is considered superior is especially worrying to some.

"Commodification is a concern whenever any monetary value is placed on human oocytes [eggs], but particularly when high values are placed on human oocytes from donors with specific characteristics — a practice that also raises eugenic concerns," wrote the researcher, Aaron D. Levine, a professor of public policy at the Georgia Institute of Technology, in a paper in The Hastings Center Report.

(Commodification is the transformation of a good or service not generally considered a commodity into such a product.)

Yet most of the ads Levine found in his study contained appearance or ethnicity requirements for donors.

The problem is that there are few oversights to make sure fertility clinics and egg donation agencies obey the guidelines, and there are few serious consequences for those who flout the rules.

Levine's study, completed in spring 2006, involved tallying the fees being offered and other characteristics of the various ads for recruiting egg donors.

Top dollar

He found that only about half of the ads offered $5,000 or less – within the guidelines. Advertisements in the Harvard Crimson, the Daily Princetonian, and the Yale Daily News offered $35,000, and an ad in the Brown Daily Herald offered $50,000 to "an extraordinary egg donor." Many of these high-end fees were promised on behalf of particular couples using agencies to recruit a donor.

Other objections to such high fees for egg donors rest on the worry that the money could induce women to overlook the risks or drawbacks of donating, potentially creating a situation in which women are being exploited. Egg donation typically pays much more than sperm donation, but that is thought to be justified because egg donation is a more medically invasive and time-consuming procedure.

Some people argue that the generous fees aren't necessarily unethical.

"It may lead some women to become egg donors who would not otherwise do so, but that does not mean that they have been exploited, much less unfairly induced," wrote law professor John A. Robertson of the University of Texas in a related commentary in The Hastings Center Report. Robinson is a previous chair of the ASRM ethics committee, and was not involved in Levine's study.

He pointed out that banning payments to egg donors would drastically reduce the number of donated eggs available, presumably because the financial compensation is a large part of the motivating factor for egg donors.

"The ASRM never says what is wrong with paying women who are healthier, more fertile, have a particular ethnic background, a high IQ, or some other desirable characteristics," Robinson wrote. "The charge of 'commodification'; is easily hurled but not easily justified. After all, we allow individuals to choose their mates and sperm donors on the basis of such characteristics. Why not choose egg donors similarly?"

The Hastings Center Report is a publication of The Hastings Center, a nonpartisan bioethics research institution in Garrison, N.Y.