How the Public Perceives Science

This ScienceLives article was provided to LiveScience in partnership with the National Science Foundation.

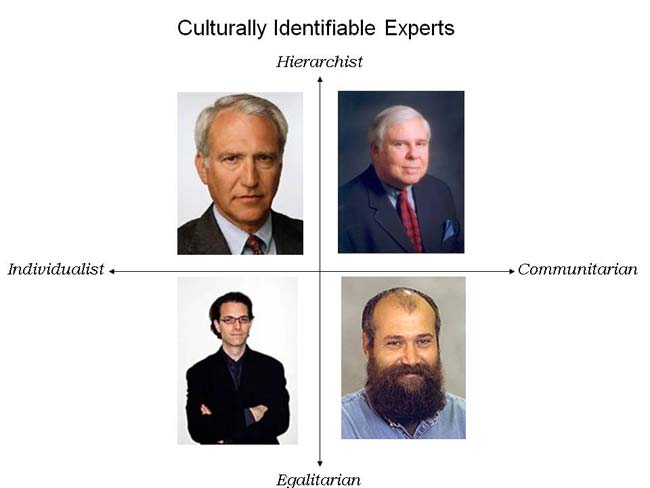

Dan Kahan of Yale Law School is a member of the Cultural Cognition Project, an interdisciplinary team of scholars who examine how group values shape individuals' perceptions of risk and related factors. He and his collaborators have investigated beliefs about climate change, assessments of the risks and benefits of universally vaccinating school girls against infection by the human papillomavirus virus (HPV), and the formation of beliefs and attitudes about nanotechnology. The Cultural Cognition Project is currently engaged in an NSF-supported program aimed at identifying how public perceptions of the risks and benefits of synthetic biology are likely to evolve as synthetic biology assumes a higher public profile. Kahan's research has also examined how cultural cognition can influence perceptions of fact-finding in law, a major focus of his teaching of Evidence and other subjects at Yale Law School. Read more about Kahan and his work in Who's Afraid of the HPV Vaccine?, and see the related webcast. Below, Kahan answers the ScienceLives 10 Questions.

Name: Dan Kahan Age: 46 Institution: Yale Law School Field of Study: Risk Perception and Science Communication

What inspired you to choose this field of study? A paradox: At no point in human history have we had possession of more scientific knowledge relevant to public policy (on protecting the environment; on promoting public health; on attaining security; on our streets and at our borders), yet at no time — at least as far as I can tell — have we had more public disagreement about the threats and dangers we face and what steps will be most effective to repel them. This fascinates me as a scholar. It concerns me as a citizen. My research is aimed at understanding why there is so much conflict on policy-relevant science and at contributing, if I can, to dispelling such disagreements.

What is the best piece of advice you ever received? From a grade school teacher (who put it in terms I was able to understand then): Don't shun uncertainty, ambiguity or complexity; embrace them, because they are the occasions for learning something.

What was your first scientific experiment as a child? I don't recall all the details — I likely have suppressed them — but I'm sure it involved my younger brother and would not have been approved by any human subjects review committee.

What is your favorite thing about being a scientist or researcher? Scholarly leisure: I am permitted and generously enabled by others to satisfy my curiosity as my life's work. I like to describe my job as "student for life;" in fact, my job is even better than that, because I get all the benefits of being a student — being free to commit my energy to learning new and interesting things — and yet I never have to endure all the unpleasantness of final exams!

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

What is the most important characteristic a scientist must demonstrate in order to be an effective scientist? I am reluctant to state what the most important characteristic is; surely some degree of humility, and reluctance to make claims about what one has opinions on, but realizes one doesn't have strong evidence for, are among the important characteristics! Add to those curiosity and passion for learning — including appreciation of the experience of surprise to discover one's opinions were wrong and must be revised — and one is likely at least to have the aptitude to be an effective scientist.

What are the societal benefits of your research? I think it is a benefit in itself to understand who disagrees about what and why on facts that are relevant to policy and that are amenable to scientific investigation. But I hope, too, that by contributing to the understanding of those things, I can also contribute to the formation of procedures and institutions that make it possible for diverse citizens to recognize the best available scientific knowledge of how to achieve their common ends and to use that knowledge effectively as they engage in genuine self-government.

Who has had the most influence on your thinking as a researcher? Surely my collaborators in the study of the cultural cognition of risk. Not only have I lost count of the number of ideas, and the number of concepts and techniques useful for investigating them, that they have imparted to me; at this point, I could not tell you what it is that I know, or what I know how to do, that isn't attributable to their ideas and skills.

What about your field or being a scientist do you think would surprise people the most? The most surprising thing is how far behind our science (or sciences) of policymaking is from our science of communicating science to citizens of a democracy. Remarkably, it doesn't seem to occur to most people (including most scientists) that communicating science in a diverse, self-governing society is a problem whose solution itself admits of, and indeed requires, scientific knowledge.

If you could only rescue one thing from your burning office or lab, what would it be? My cat. My data are backed up; she isn't.

What music do you play most often in your lab or car? A wide variety of things — but always on my "iPod nano," my appreciation of which has been significantly increased by the work I've done with my collaborators on the formation of nanotechnology risk perceptions.

Editor's Note: This research was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF), the federal agency charged with funding basic research and education across all fields of science and engineering. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. See the ScienceLives archive.