Saturn's Aurora Heartbeat Discovered

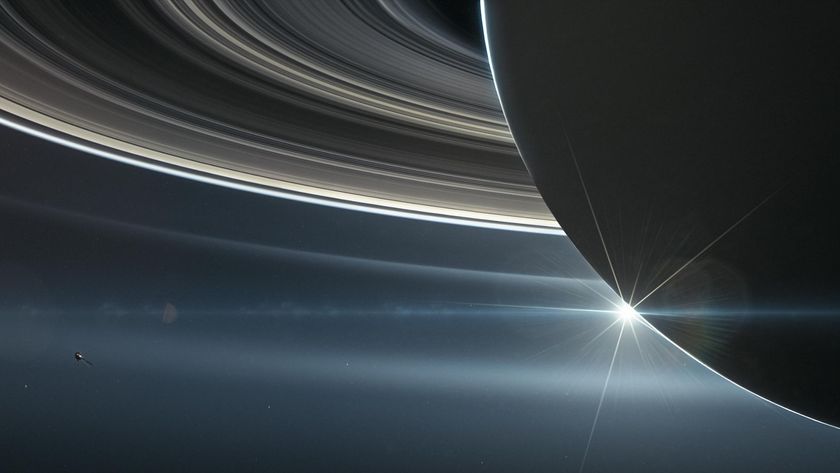

Saturn's aurora, a ghostly ultraviolet glow that illuminates the gas giant's upper atmosphere near the poles, has a heartbeat that pulses in tandem with the planet's radio emissions, scientists have discovered.

The pulsing auroras on Saturn occur about once every 11 Earth hours or so — the length of one day on the ringed planet, researchers found.

"This is an important discovery for two reasons," said study leader Jonathan Nichols of the University of Leicester in England. "First, it provides a long-suspected but hitherto missing link between the radio and auroral emissions, and second, it adds a critical tool in diagnosing the cause of Saturn's irregular heartbeat."

Saturn's heartbeat

Like all magnetized planets, Saturn emits radio waves into space from its polar regions.

These emissions pulse at intervals of about 11 hours. During the twin Voyager missions, both launched in 1977, the timing of the pulses were thought to represent the planet's rotational period.

But, observations over the years noted that the pulsing of the radio emissions has varied. Since the rotation of a planet cannot easily change speed, the source of Saturn's fluctuating radio period mystified planetary scientists.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Similarly, the length of a day on Saturn has generated debate, since traditional clocks are unreliable timekeepers in determining the rotational period of a planet with no solid surface for reference.

In a new study, researchers show that, not only do radio emissions pulse, the planet's auroras also beat in tandem.

Auroras on Saturn

Nichols and his team used images of Saturn's auroras from the Hubble Space Telescope that were obtained between 2005 and 2009. The findings of the study will be published in the Aug. 6 edition of the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

On Earth, auroras are caused when charged particles in space stream down the planet's magnetic field lines toward the poles. The interaction of these particles with atoms of nitrogen and oxygen in the Earth's atmosphere cause them to glow.

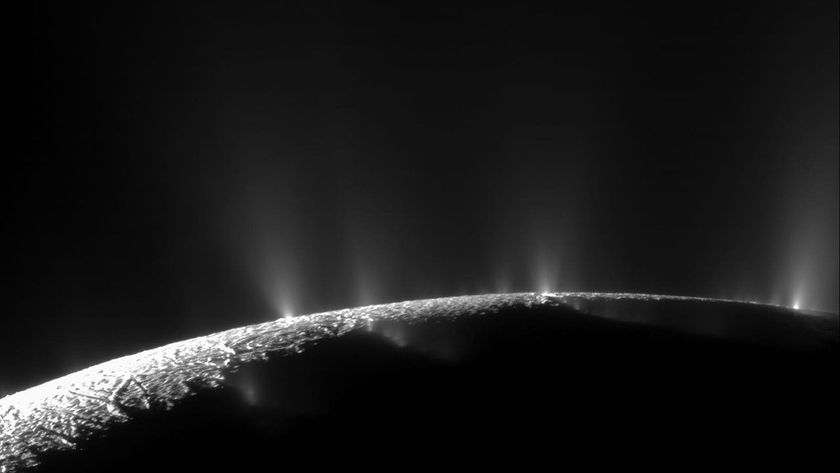

Auroras on Earth can occur when the planet's magnetic field is bombarded by particles emitted by the sun. On Saturn, auroras can occur when moons such as Enceladus or Io expel particulate material into the near-planet space.

It was long suspected that Saturn's radio waves were emitted by these charged particles as they traveled toward the poles, but radio-like pulsing had not been observed in Saturn's aurora. This puzzled astronomers, since the two phenomena were seemingly related.

In this recent study, however, Nichols and his team of researchers used the clock of Saturn's radio pulsing to organize the planet's aurora data.

They also stacked the results from all of Hubble's Saturn aurora images (obtained from 2005 to 2009) on top of each other. By doing this, the aurora pulsing finally revealed itself.

"This confirms that the auroras and the radio emissions are indeed physically associated, as suspected," Nichols said. "This link is important, since it implies that the pulsing of the radio emissions is being imparted by the processes driving Saturn's aurora, which in turn can be studied by the NASA/ESA spacecraft Cassini, presently in orbit around Saturn. It thus takes us a significant step toward solving the mystery of the variable radio period."

Denise Chow was the assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. Before joining the Live Science team in 2013, she spent two years as a staff writer for Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University.