Remains of Ancient Feast to Honor Dead Shaman Discovered

Prehistoric leftovers of a feast 12,000 years ago at an apparent shaman's gravesite have been unearthed in what is now Israel. Archaeologists say the ritual might be the first clear evidence of feasting in early humans, a sign of the kinds of increasingly complex societies that proved crucial to the dawn of agriculture.

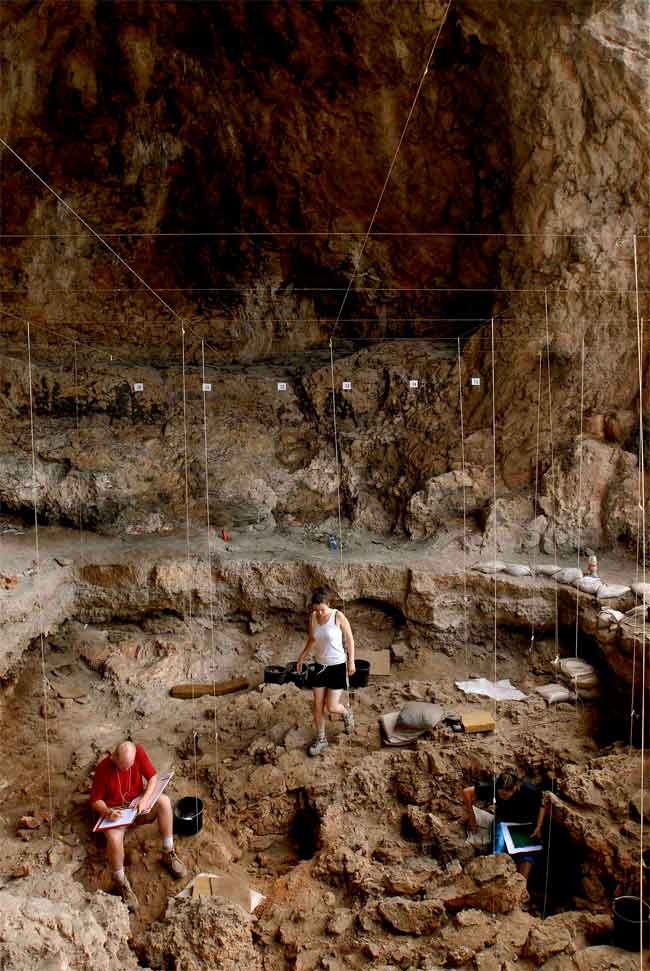

In a cave above a creek in the Galilee region of northern Israel, scientists discovered the body of a petite, elderly, disabled woman, most probably a shaman, in 2005. As they continued to excavate, they found the woman apparently was intentionally laid to rest in a specially crafted hollow between the remains of at least 71 Mediterranean tortoises, as well as with seashells, beads, stone tools and bone tools. In a separate pit nearby, they also found bones of at least three wild, extinct cattle known as aurochs.

The cattle bones showed clear signs of butchery, with the bones cracked for marrow, while there were enough tortoises to supply meat for at least 35 people. Signs of burning were seen on both the cattle and turtle remains, suggesting they were cooked.

Altogether, these large amounts of meat seen in these roughly 12,000-year-old deposits might be remnants of a ritual feast held to commemorate the dead shaman, the researchers said.

Ancient feasts

The act of sharing food communally in a feast is one of the most universal and important behaviors seen in humanity, taking center stage in everything from the Last Supper to Thanksgiving. Although evidence for feasting is common in the early agricultural societies of the Neolithic, such evidence of pre-Neolithic, pre-agricultural feasting proved more elusive until now.

"Scientists have speculated that feasting began before the Neolithic period, which starts about 11,500 years ago," said researcher Natalie Munro, a zooarchaeologist at the University of Connecticut at Storrs. "This is the first solid evidence that supports the idea that communal feasts were already occurring, perhaps with some frequency, at the beginnings of the transition to agriculture."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In this period, once-nomadic groups of people were settling down into lasting communities, which could place tremendous pressure on local resources. Population growth also ramped up, meaning people were coming into contact with each other a lot more often, "and that can create friction," Munro said.

"Before, they could get up and leave when they had problems with the neighbors," she explained. "Now, these public events served as community-building opportunities, which helped to relieve tensions and solidify social relationships."

The food that binds

Feasting may have thus helped people bond, easing the shift toward full-fledged agricultural societies.

"We believe that the detection of feasting at this early date signifies important culture changes," Munro told LiveScience. "These rituals foreshadow those that occur later in the Neolithic agricultural period. The fact that these rituals are becoming more intensive at an earlier date than previously indicated demonstrates that the social changes that accompany the agricultural transition were already in place at its very beginning."

The researchers are now working on completing the analysis of all the other remains at the site to provide broader context regarding the rituals and burials that occurred in the cave, Munro said.

Munro and her colleague Leore Grosman detailed their findings online Aug. 30 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.