Breakthrough Untangles One Key to Alzheimer’s Disease

Scientists may have found a new way to reduce levels of a toxic protein that accumulates in the brains of Alzheimer's patients. The approach may one day lead to new therapies for the condition.

In patients with certain neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's, a protein called tau forms stringy blobs known as "tangles" inside brain cells. These tangles, along with brain plaques, are thought to contribute to the development of the disease.

Normally, tau proteins help maintain the cell's structure. But in Alzheimer's patients, they've become toxic because they've undergone a certain kind of chemical change, called phosphorylation. Brain cells should recognize that these changed tau proteins are damaged, and should destroy them. But this destruction doesn't happen, and scientists have not understood why.

Li Gan, a researcher at the Gladstone Institute of Neurological Disease in San Francisco, and her colleagues wondered whether these damaged tau proteins might be modified in some other way that prevents the cells from demolishing them.

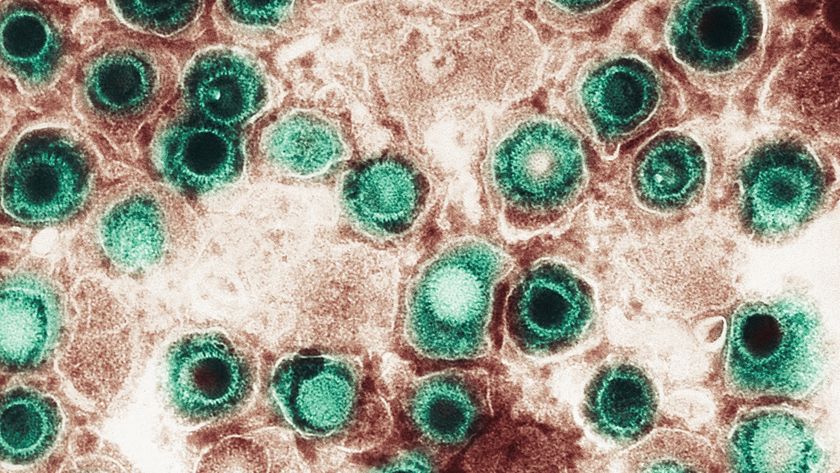

They discovered a second chemical change that the toxic tau proteins have undergone, called acetylation, which makes them destruction-proof. In both mice with Alzheimer's and humans with Alzheimer's, levels of this destruction-proof tau protein were elevated at early and middle stages of the disease — before the tangles appeared.

And when they blocked the second change, levels of the damaging proteins in the cells were greatly diminished.

"We can actually make the cell more efficient," in getting rid of the damaged tau proteins, Gan told MyHealthNewsDaily.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The molecule the researchers used to block the second change might one day serve as a new class of anti-Alzheimer's disease drugs, Dr. Lennart Mucke, GIND director, said in a statement.

The researchers said the second change might work by preventing the toxic tau protein from being "tagged" for demolition by the cell.

The study will be published tomorrow (Sept. 23) in the journal Neuron.

- 10 Things You Didn't Know About the Brain

- Study: Disease, Not Old Age, Causes Forgetfulness

- Sleep Disorder Reveals Parkinson's Disease Risk

This article was provided by MyHealthNewsDaily, a sister site to LiveScience.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.