Jupiter's Missing Cloud Stripe Bounces Back Big Time

This story was updated at 8:09 a.m. ET, Nov. 25.

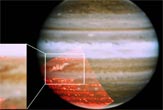

The dark brown stripe of clouds on Jupiter that disappeared from view last year is reappearing.

Astronomers confirmed Wednesday (Nov. 24) that the gas giant’s South Equatorial Belt (SEB), one of two distinctive dark stripes formed by the planet's cloud chemistry and winds, is coming back. They attributed the return of the view to a shift in Jupiter’s cloud cover.

An amateur astronomer, Christopher Go of the Philippines, spotted the stripe's reappearance earlier this month. Now scientists, armed with observations from NASA's Infrared Telescope Facility, the 10-meter Keck telescope and the 8-meter Gemini telescope, all atop Mauna Kea in Hawaii, have confirmed the finding. [Photo of Jupiter's returning cloud stripe]

Go spotted the beginning of the horizontal stripe's revival on Nov. 9, when it appeared as a white blotch, and has been tracking it ever since. It should take between four and six months to return entirely, he said.

"This is a very textbook revival," Go told SPACE.com in an e-mail. "It is following historic revival patterns. We are just seeing more of the details now."

The dark band had been temporarily obscured by a white cloud deck made of ammonia ice, scientists now say.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The reason Jupiter seemed to 'lose' this band — camouflaging itself among the surrounding white bands — is that the usual downwelling winds that are dry and keep the region clear of clouds died down," said Glenn Orton, a research scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., in today's announcement. "One of the things we were looking for in the infrared was evidence that the darker material appearing in visible light was actually the start of clearing in the cloud deck, and that is precisely what we saw."

Every few decades the South Equatorial Belt appears to disappear, its location turning completely white for around one to three years. These events have puzzled scientists for decades.

Such an extreme change in appearance has only been seen with the South Equatorial Belt, making it unique to Jupiter and the rest of the solar system.

"At infrared wavelengths, images in reflected sunlight show that the spot is a tremendously energetic 'outburst,' a vigorous storm that reaches extreme high altitudes," said Imke de Pater, a University of California, Berkeley professor of astronomy. "The storms are surrounded by darker areas, bluish-gray in the visible, indicative of 'clearings' in the cloud deck."

The South Equatorial Belt underwent a slight brightening, known as a "fade," just as NASA's New Horizons spacecraft was flying by in 2007 on its way to Pluto. Then there was a rapid revival of its usual dark color three to four months later. Go was the first to discover that revival as well, he said.

"I would say that this is more spectacular than the revival of 2007," said Go, who also spotted the cloud belt's last revival. "This is because in 2007, the SEB did not completely fade and the revival started 'prematurely.'"

The last full fade and revival was a doubleheader event, starting with a fade in 1989, revival in 1990, then another fade and revival in 1993. Similar events were seen and captured photographically back to the early 20th century, and they are likely to be long-term phenomena in Jupiter’s atmosphere.

Scientists are particularly interested in this event because it’s the first time they've been able to use modern instruments to determine the details of the chemical and dynamic changes.

"These observations may help to unravel the mystery of why this transition occurs, and may allow us to understand the longevity of Jupiter's belt/zone structure," said Leigh Fletcher, a scientist at Oxford University in England.

- Gallery - Jupiter Gets Slammed by an Asteroid

- The Wildest Weather in the Galaxy

- Jupiter Has Lost a Cloud Stripe, New Photos Reveal

This article was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site of LiveScience.com.