Despite a barrage of criticism from fellow scientists, a researcher involved in a new study describing a bacterium that thrives on arsenic said today (Dec. 7) that his team stands behind its findings.

The study, which was published in the journal Science on Dec. 2, claimed that a strain of bacteria from a briny California lake can incorporate arsenic into its DNA and other vital molecules, in place of the usual phosphorus.

The finding, if true, would change scientists' perceptions of what life on Earth is capable of. But in the past few days, outside researchers have voiced serious concerns about the study's methods and conclusions, with some going so far as to say the work never should have been published.

During a lecture today at NASA headquarters in Washington, D.C., study co-author Ron Oremland defended his team's work and said the criticism is a natural part of the scientific process.

"Science works in a certain way. It's resistant to change," said Oremland, a scientist with the U.S. Geological Survey in Menlo Park, Calif. "But if you look qualitatively at our data, it's compelling."

The study's scientists declined to speak with individual reporters about the criticism, saying they want to keep the discussion in the scientific literature as much as possible.

Raising concerns

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

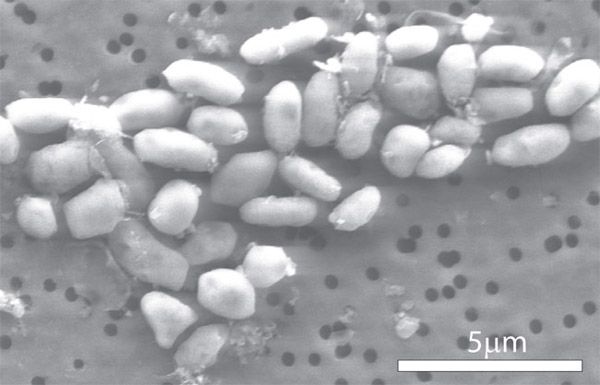

The research team, led by Felisa Wolfe-Simon — currently a NASA astrobiology research fellow at the USGS in Menlo Park — collected a strain of bacteria called GFAJ-1 from California's arsenic-rich Mono Lake. (GFAJ-1 stands for "Give Felisa A Job")

The scientists took the microbe back to the lab and grew it in several different environments. They deprived GFAJ-1 of phosphate — a molecule composed of a phosphorus atom and four oxygen atoms — replacing the stuff with arsenate (one arsenic atom surrounded by four oxygen atoms).

Wolfe-Simon and her team found that GFAJ-1 continued to grow, even without phosphate. Subsequent analyses suggested that the microbe had incorporated arsenic into its DNA in place of phosphorus, the researchers said.

This was big news, since scientists had regarded phosphorus as one of six key ingredients — along with carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen and sulfur — that all life on Earth needs to survive.

But over the weekend, some outside scientists began to question the team's findings. Some aren't convinced that GFAJ-1 actually takes arsenic up into its DNA, saying that the researchers may have just detected arsenic stuck to the outside of the microbe's DNA.

Other researchers contend that the growth medium contained enough phosphorus — as a contaminant — for GFAJ-1 to scratch out a living without having to swap it out for arsenic. Microbes are known to subsist on minuscule amounts of phosphorus elsewhere, such as the Sargasso Sea, critics said.

And other scientists pointed out that arsenate compounds are extremely unstable in water, breaking down in minutes without some kind of compensatory stabilizing mechanism, such as special molecules to keep the compound intact. Wolfe-Simon and her team dunked GFAJ-1 in water during the analysis process, yet the microbe's DNA didn't get sliced into many tiny pieces — it remained in large chunks.

This further hints that the microbe's DNA contained the "normal" phosphate rather than arsenate, some said.

"There's a class of hypotheses which, as Carl Sagan says, are exceptional and therefore require exceptional evidence," biochemist Steven Benner of the Foundation for Applied Molecular Evolution in Gainesville, Fla., told LiveScience. "We are not expecting this result to survive." Benner was not involved in the arsenic-bacteria finding.

Defending the findings

Oremland acknowledged the critics' arguments, saying that the many other tests they suggest performing would be valuable and worthwhile.

"There's dozens and dozens of things that could be done, and should be done," he said. "We can't do everything."

But he stuck behind his team's findings.

"I think we had enough to get the point out," Oremland said. "Certainly the [paper's] reviewers liked it, and now the community is going to judge."

He also said the small amount of phosphorus present in the growth medium as a contaminant wasn't as big a deal as the paper's critics have alleged.

"There's a smidgen of phosphorus in the medium," he said. "We didn't do anything fancy to get rid of it. But it's not enough to sustain growth. That's very clear."

In the end, Oremland said, science will move forward as other groups try to reproduce the team's results. And that's the way things should be.

"They may prove us wrong, or they may reproduce the results and find new stuff," he said. "It's the way the process works."

Extremophiles: World's Weirdest Life

Gallery: Strangest Alien Planets

Strangest Places Where Life Is Found on Earth

Mike Wall is a Senior Writer at SPACE.com, a sister site of LiveScience.