Giraffe-sized Flying Reptile Snaps Together in Minutes

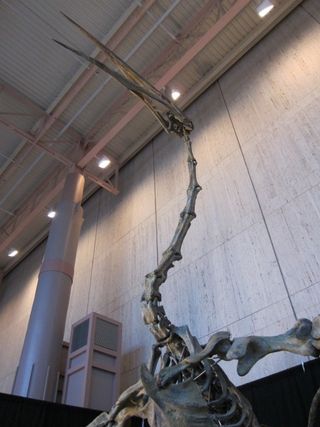

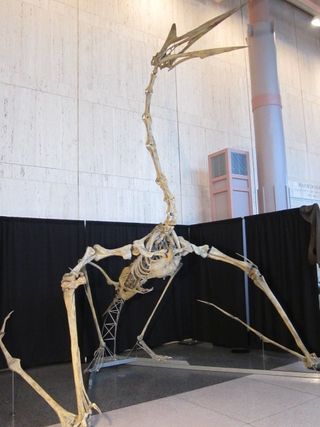

HOUSTON – The scene at the Houston Museum of Natural Sciences Friday (Jan. 14) was a model enthusiast's dream. Working in front of a crowd of visitors, a museum crew pieced together a fossil replica of an ancient flying reptile with a 36-foot wingspan. That's just a few feet shy of the length of an average school bus.

The creature, Quetzalcoatlus northropi, is an anatomical mash-up, with a neck like a giraffe, a beak like a stork and the on-ground gait of — wait for it — a vampire bat. It lived at the end of the Cretaceous period 65 million years ago. Recent research suggests these winged reptiles, or pterosaurs, may have stalked grassy plains on foot, jabbing at small dinosaur prey with their pointed beaks. They may have shared the agile, spider-like movements of modern-day vampire bats, said David Temple, the associate curator of paleontology at HMNS.

"I gotta be honest with you, you know dinosaurs, I love 'em, they don't really bother me," Temple told LiveScience. "This thing kind of gives me the creeps, just the way it would move on the ground."

Temple and other exhibit planners hope to give museum visitors the creeps, or at least a thrill, with the newly assembled model fossil. The skeleton is based on a fossil found in Big Bend National Park in west Texas. The real fossil skeleton is incomplete and far too fragile for display, so paleontologists are turning to fossil casts, the action figures of the museum world. Casts aren't as fragile as real fossils, making them much more flexible for posing purposes. They're also easier to put together: While a real dinosaur skeleton takes weeks to assemble, a three-man crew put the Quetzalcoatlus model together in about a half-hour.

The fossil replica will be part of a life-sized diorama in the museum's expanded paleontology hall, set to open in 2012, Temple said.

"The way we're designing it, is when visitors come through, you are caught between angry Quetzalcoatlus that are defending their nest and a curious juvenile T. rex," Temple said. "You're right in the middle, you're right there."

It's a tableau that could easily have occurred in the late Cretaceous, right before an asteroid slammed into what is now the Yucatan Peninsula and likely caused or contributed to the downfall of the dinosaurs. As a resident of what is now west Texas, Temple said, Quetzalcoatlus would have had front-row seats for the apocalypse.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In many ways, however, Quetzalcoatlus is an "enigma," Temple said. It had enormous wings, but scientists aren't sure if it could even fly.

Research presented in 2002 to the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology argued that these pterosaurs were big but not dense, weighing in between 136 and 170 pounds (62 and 77 kilograms). Many researchers peg the creature's weight in the 220-pound (100 kg) range, Temple said, while others argue they were much heavier. In a paper published in 2010 in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Canadian researcher Donald Henderson calculated that Quetzalcoatlus northropi tipped the scales at almost 1,200 pounds (544 kg).

In other words, no one knows how much Quetzalcoatlus weighed, so no one knows if it could have gotten aloft. Until more-complete fossil skeletons are found, no one will know for sure.

The HMNS Quetzalcoatlus cast will tower over the museum hall over the weekend before being packed away again, Temple said. Museum crews will measure it to plan its place in the upcoming diorama, where it will join two other Quetzalcoatlus casts in defense of its nest.

Where science waffles, imagination flourishes: One of the Quetzalcoatlus skeletons will be airborne, Temple said.

- Top 10 Beasts and Dragons: How Reality Made Myth

- Rate: Dinosaurs That Learned to Fly

- Image Gallery: Dinosaur Art

You can follow LiveScience Senior Writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.