Deadliest Hurricane Threat: Inland Heavy Rain

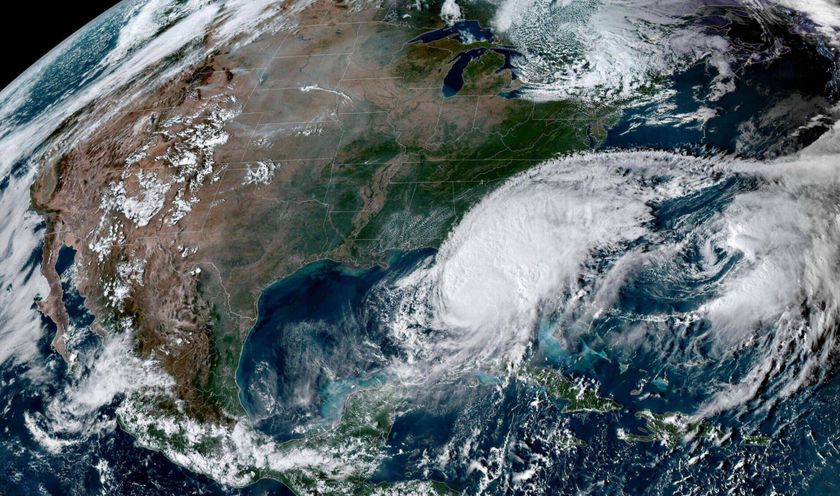

With Hurricane Dean crashing ashore in Mexico, some of the worst damage could actually occur far inland.

Though coastal areas bear the brunt of a hurricane's fury, its winds and rain continue to wreak havoc as the storm moves inland. Because of this inland threat, a researcher has now developed a way to improve rainfall forecasts for those in the path of the hurricane once it’s ashore.

While in the past hurricanes were generally deadliest at the coast, improved forecasts have given coastal residents more time to prepare and evacuate before a storm hits.

Now, a higher proportion of hurricane fatalities are occurring inland as a result of unusually heavy rainfall. Almost two-thirds of deaths from tropical storms and hurricanes between 1970 and 1999 occurred because of heavy rainfall, geographer Corene Matyas of the University of Florida noted in her research, detailed in a recent issue of the journal Professional Geographer.

Heavy rainfall inland tends to create flash floods, which can be very deadly. Meteorologists have known for some time that it is the combination of these floods and storm surge that are the biggest killer in hurricanes, not the storms' winds.

"The key is that most of the deaths come from water," said Dennis Feltgen, a spokesman for the National Hurricane Center.

Dean, which reached Category 5 status before landfall, is expected to dump between 5 to 10 inches over the Yucatan Peninsula and surrounding areas, which could bring dangerous floods and mudslides, according to National Hurricane Center advisories.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Storms tend to produce less rain as they move away from oceans, but their intensity, as well as how far they move inland and the local landscape, also affects where and how hard hurricane rains fall.

"There are a lot of different things that can affect where the rainfall can occur in the storm and how heavy that rainfall will be," Matyas said. "Our goal is to work toward predicting how those factors will determine the rainfall pattern."

Predictions of inland rainfall could have been useful when Tropical Storm Erin dumped huge amounts of rain in Texas recently, creating floods that caused several deaths.

Researchers have models to forecast inland rain patterns, but it has been difficult to account for the lopsided shape that a hurricane's rain shield (or bands of rain) takes, a factor that leads to most of the rain falling on one side of the storm.

To help improve predictions, Matyas looked at radar data from 13 hurricanes that made landfall in the United States between 1997 and 2003, and used a geographical information system, or GIS, to analyze the spatial patterns of the rain bands as they moved over land.

She found that the orientation of the bands matched closely to the orientation of the topography of the land below. For example, storms near the Appalachian Mountains tended to line up parallel to the mountains, with the heaviest rain falling consistently to the west of the storm's track.

Frank Marks, a research meteorologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, said that Matyas' findings "have a lot of merit in terms of understanding the structure, size and shape of the rain shield," but the next step is to better predict rainfall amounts.

- Video: Watch Hurricane Dean Evolve

- Warm Seas: Why Dean is So Powerful

- Quiz: Test Your Hurricane Knowledge

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.