Watch and Learn: Physics Professor Walks on Fire

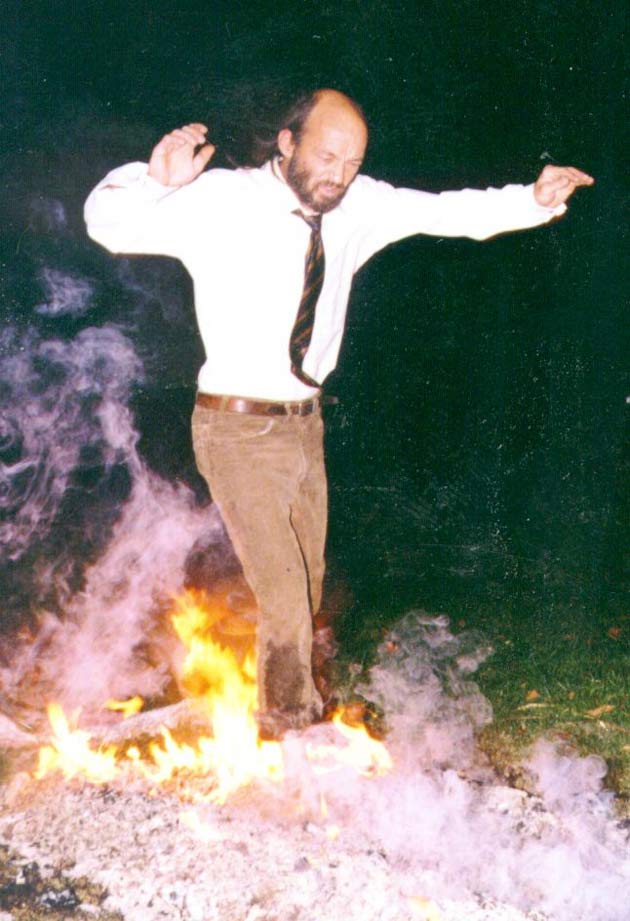

Physics professor David Willey doesn't use chalk and formulas to spark his students' interest in thermodynamics.

He walks on fire.

"Nothing gets a student's attention like the possibility that I might kill myself," said Willey, this year's winner of the President's Award for Excellence in Teaching at the University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown.

In reality, Willey doesn't even break a sweat, thanks to wood's insulating properties and a quick pace. And he's not alone.

The ritual of walking on fire has existed for thousands of years. The first records of the practice date back to 1200 B.C. Around the world, from Greece to China, cultures set trails ablaze for rites of healing, initiation, and faith. In the United States, fire-walking has become popular as a team spirit-building business for corporations as well as a so-called alternative health remedy.

Witchcraft in the wood

Scientists in the 1930's first sought explanations for how participants of the ritual paced unscathed. The University of London's Council for Physical Research found that the witchcraft was in the wood, rather than religious faith and supernatural powers.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

- Bad Breath: Causes and Cures

- The Real Scoop on Rumors and Gossip

- How Cacti Survive: Surprising Strategies Quench Thirst

Traditional fire-walking paths are made of wood, left to burn into smoldering coals. The coals can reach high temperatures. Most fire-walks occur on coals that measure about 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit.

Willey once recorded someone walking on 1,800-degree coals.

People survive because only a small amount of heat transfers from the glowing wood to the sole of their feet.

"Even if it's on fire, wood is a lousy conductor," Willey said.

Conduction is one way that heat travels from one material to the next. Vibrating molecules of a hot material collide with more calm molecules of a cooler object, and transfer energy. The low thermal conductivity of wood means that heat stays trapped in the coals, transferring little heat to the feet.

A layer of ash on the top of the flaming path helps to further insulate the heat of the coals.

Fire-walkers choose not to march on fiery steel for good reason. With high levels of conductivity, most metals would make painful paths.

Cold feet not required

Keeping a quick pace also keeps blisters at bay.

While one foot steps on the red-hot coals, the opposite foot has a chance to cool while lifted in the air. The protective layer of dead skin on the soles of your feet and calluses add extra protection.

While no one should try to do this without proper training from an experienced fire-walker, any healthy person can walk on fire, as long as it's not too hot, according to Willey. It's a matter of stepping up to the start line with courage and training your brain to get your foot to take the first step.

"You could keep on going forever and ever," Willey told LiveScience. "It's just a question of how much wood you want to cut."

- Why Knuckles Crack and Joints Creak

- Quicksand Myth Debunked: You Can Float Free

- The Most Popular Myths in Science