Recession May Boost Life Expectancy

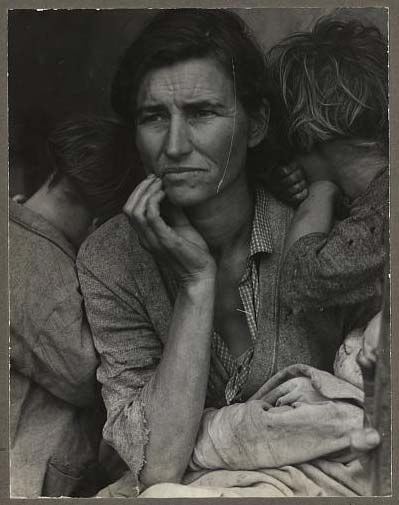

During the Great Depression, some of the hardest times our country has faced, the average life expectancy in the United States actually rose. This surprising bump in the population’s health is also seen in other economic downturns — likely even the current one.

University of Michigan researchers José Tapia Granados and Ana Diez Roux found this unexpected boost when they examined historical life expectancy and mortality data for the years 1920 to 1940.

Over that time, U.S. life expectancy increased by 6.2 years during the Great Depression — from 57.1 years in 1929 to 63.3 years in 1933 — they found. The increase held for men and women, white and non-white.

"The finding is strong and counterintuitive," Tapia Granados said. "Most people assume that periods of high unemployment are harmful to health."

Six causes

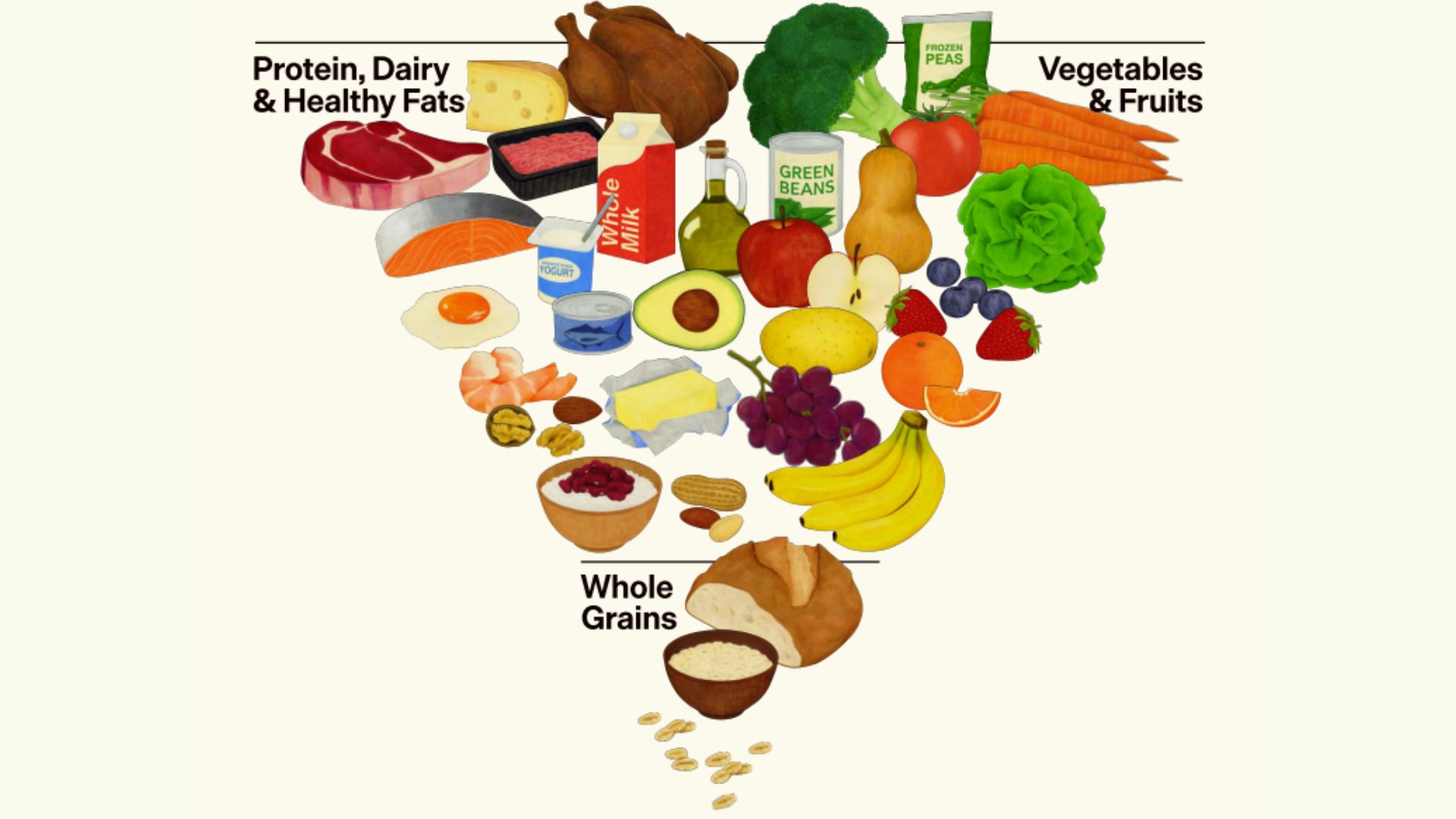

Over the entire 20th century, the life expectancy of Americans has been on the rise, for a variety of factors, including better diets and medical advances. However, among the biggest factors has been the steep drop in infant mortality rates in recent decades compared to the early part of the 20th century.

But the steady rise went up a little faster in some periods than others. The data examined by Tapia Granados and Diez Roux found that while overall population health (as measured by life expectancy) rose during the four years of the Great Depression and other recessions between 1921 and 1938, mortality increased during periods of strong economic expansion, such as 1923, 1926, 1929 and 1936-37.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"This is a pattern that is found again and again," Tapia Granados said.

The researchers looked at mortality rates for specific age groups and as a result of six specific causes that accounted for about two-thirds of total mortality in the 1930s: cardiovascular and renal diseases, cancer, influenza and pneumonia, tuberculosis, motor vehicle traffic injuries, and suicide.

Mortality for all ages due to all the causes declined in periods of economic downturn, except for suicide.

Less stress

The research didn't analyze possible causes for the counterintuitive rise in life expectancy, but Tapia Granados offers a few possibilities. Among them: the change in working conditions between boom times and recessions.

"During expansions, firms are very busy, and they typically demand a lot of effort from employees, who are required to work a lot of overtime, and to work at a fast pace," Tapia Granados said.

That faster pace generates more stress, which could lead to an uptick in unhealthy behaviors such as smoking and drinking, he added. Adding to this, people also might sleep less and eat unhealthy fast foods. Stress alone is known to increase the odds of a host of diseases and increase the risk of premature death.

"Also, new workers may be hired who are inexperienced, so injuries are likely to be more common," Tapia Granados said.

Conversely, in recessions, there is less work to do, so employees can work at a slower pace and have more time to sleep. And because there is less money, people are less likely to spend on non-necessities like alcohol and tobacco.

Increases in atmospheric pollution that happen when boom times stimulate industrial production could also tax the population's health, the researchers suggest.

Today's recession

These same factors likely hold true during the current recession, though there are significant economic and societal differences between now and the 1930s, Tapia Granados told LiveScience.

He did note, though, that while overall population health and life expectancy may improve during down times, that might not be the case for any particular individual, especially someone who is unemployed or serious worried about getting laid off and suffering attendant stress.

The overall rise still happens, despite potential health declines in those who have lost their jobs, because the majority of the work force is still employed (or retired and receiving benefits), he explained.

The findings were detailed in the Sept. 28 issue of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.