Ancient Hindu Text Preserved by Modern Technology

Hidden in a wooden chest in the heart of a monastery in Udupi, India, an ancient Hindu manuscript has been deteriorating bit by bit over the last 700 years. Now with the help of modern imaging technologies, scientists are illuminating the seemingly invisible Sanskrit.

Once they have brought to light the holy words, the researchers will close the book forever.

The project is led by P.R. Mukund and Roger Easton, both of Rochester Institute of Technology. They are digitally preserving the original Hindu writings known as the Sarvamoola granthas. This collection of 36 works was written by Shri Madvacharya (1238-1317), a philosopher whose ideas had a far-reaching impact on the Indian society.

Madvacharya inscribed in Sanskrit comments on the Hindu scriptures, conveying his Dvaita philosophy of the meaning of life and the role of God.

Crumble to dust

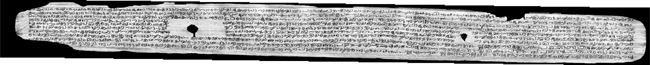

In December 2005, the researchers traveled to the monastery Palimaru to examine the manuscript. Inside a wooden chest, the researchers saw the book's outer wooden covers. Sandwiched between the covers, they found 340 palm leaves, each 26 inches long and 2 inches wide, bound together with braided cord threaded through two holes.

The original inscriptions had become so faded they were barely visible, Mukund told LiveScience.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It is literally crumbling to dust," Mukund said [image].

He expected some crumbling due to normal wear and tear during seven centuries. But he also found some of the leaves sticking together. Some years ago, Mukund said, a scientist had come up with a preservation technique in which the pages were coated with an oil substance to soften the pages.

"That worked great," Mukund said. Then, the preserver apparently recoated the palm leaves, which Mukund said led to the stickiness.

According to Mukund, 15 percent of the manuscript is missing.

Technology to the rescue

The team returned to the monastery in June and spent six days imaging the palm leaves in infrared, which enhanced the contrast between the ink and the background leaf, which has a high reflectivity in visible light.

The leaves were so delicate and sacred, "They wouldn't let us touch these things. They had scholars who would take one leaf at a time and place it on the table" to be photographed, Mukund said. They snapped at least 10 images of each leaf, using software programs to digitally stitch together the images to look like the original leaf [image].

With this digital treasure chest of photos, Mukund said they hope to store the manuscript in various time-keeping formats, including electronically, in published books and even on silicon wafers for long-term preservation. The promising latter process, in which scientists etch the Sanskrit onto silicon wafers, will not be completed for some time, Mukund said. In November, the scientists will present the printed and electronic versions of the Sarvamoola granthas to the monastery in Udupi in a public ceremony.

And after all of this probing, the palm-leaf manuscript is secured back into its wooden chest. "They will never open it again," Mukund said.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.